Highlight

• Large germline analysis of 189 DNA damage response genes (5,993 pediatric cancer cases vs 14,477 adult noncancer controls) confirms the importance of DDR variation in childhood cancer risk and replicates known predisposition signals (eg, TP53, mismatch repair genes).</p>

• Four novel gene–tumor associations were nominated, most notably SMARCAL1 as a replicated osteosarcoma (OS) predisposition gene with supporting somatic loss of the wild-type allele.

• Findings support inclusion of DDR genes in pediatric cancer predisposition testing panels and motivate functional work, prospective surveillance studies, and family counseling tailored to newly implicated genes.

Background: Clinical context and unmet need

Germline variation in cancer predisposition genes (CPGs) is increasingly recognized as relevant to pediatric oncology. Recent estimates suggest that a nontrivial fraction of children with cancer—commonly reported between ~5% and 18% depending on cohort and gene set—harbor pathogenic or likely pathogenic germline variants. Many such variants occur in genes encoding components of the DNA damage response (DDR), which are also frequently somatically altered in pediatric tumors. However, until now there has been limited systematic interrogation of DDR genes as a class for germline predisposition signals in pediatric cancer across multiple tumor types and large cohorts.

Identifying bona fide germline predisposition genes matters for several reasons: it can inform diagnostic testing and family cascade testing, explain tumor biology and therapeutic vulnerabilities (eg, DNA repair deficiency and sensitivity to specific agents), and enable risk-adapted surveillance and prevention strategies when penetrance and phenotype are clarified. The study by Oak et al. (JCO, 2025) addresses an important knowledge gap by systematically evaluating 189 DDR genes in thousands of childhood cancer cases and independent replication cohorts to find enriched germline pathogenic variants (PVs) and to validate novel gene–tumor associations.

Study design and methods

Oak et al. conducted a case-control genetic association analysis with the following high-level features:

- Gene set: 189 DNA damage repair genes selected a priori.

- Variant classification: tiered approach using ClinVar annotations, InterVar classification, and in silico predictors (REVEL, CADD, MetaSVM) to call pathogenic/likely pathogenic variants.

- Statistics: logistic and Firth regression for enrichment testing with false discovery rate (FDR) control; cancer-specific and pan-cancer analyses performed.

- Replication: findings were tested in three independent pediatric cohorts totaling 1,497 additional childhood cancer cases (Childhood Cancer Survivor Study [CCSS], Cancer Predisposition Syndrome–German Childhood Cancer Registry [CPS-GCCR], and Individualized Therapy for Relapsed Malignancies in Childhood / INFORM-like cohorts).

- Tumor analysis: where available, tumor sequencing data were examined for evidence of second hits (eg, loss of the wild-type allele) to support tumor suppressor mechanisms.

Key findings

Overall and known associations

At the pan-cancer level, pathogenic variants in TP53 were enriched among children with cancer, consistent with its established role (Li-Fraumeni spectrum). Cancer-specific analyses validated several known associations, adding internal consistency to the study: germline TP53 PVs with adrenocortical carcinoma, high-grade glioma (HGG), and medulloblastoma (MB); PMS2 PVs with HGG and non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL); MLH1 PVs with HGG; BRCA2 PVs with NHL; and BARD1 PVs with neuroblastoma.

| Discovery analysis: Known associations | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene | Cancer | Frequency in Cases | Frequency in Controls | Cancer Risk | ||

| OR [95% CI] | Plogistic | FDRlogistic | ||||

| TP53 | Adrenocortical carcinoma (ACC) | 12 in 27 (44.44%) | 27 in 14477 (0.19%) | 426.7 [182.1 – 999.5] | 1.35E-43 | 4.86E-40 |

| TP53 | High grade glioma (HGG) | 5 in 206 (2.43%) | 27 in 14477 (0.19%) | 12.5 [4.4 – 29.9] | 8.85E-07 | 0.001 |

| PMS2 | High grade glioma (HGG) | 4 in 206 (1.94%) | 39 in 14477 (0.27%) | 10.1 [3.2 – 24.9] | 4.03E-05 | 0.017 |

| MLH1 | High grade glioma (HGG) | 4 in 206 (1.94%) | 42 in 14477 (0.29%) | 9.6 [3.1 – 23.6] | 5.31E-05 | 0.019 |

| BARD1 | Neuroblastoma (NBL) | 6 in 485 (1.24%) | 31 in 14477 (0.21%) | 6.3 [2.4 – 13.9] | 8.80E-05 | 0.023 |

| PMS2 | Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma (NHL) | 4 in 239 (1.67%) | 40 in 14477 (0.28%) | 8.1 [2.6 – 20] | 2.03E-04 | 0.037 |

| TP53 | Medulloblastoma (MB) | 4 in 257 (1.56%) | 28 in 14477 (0.19%) | 8.2 [2.6 – 20.7] | 2.47E-04 | 0.040 |

| BRCA2 | Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma (NHL) | 5 in 239 (2.09%) | 51 in 14477 (0.35%) | 6.2 [2.2 – 14] | 2.62E-04 | 0.041 |

Novel associations: four genes nominated

The investigators uncovered four novel gene–tumor associations that reached statistical significance in discovery and/or replication analyses:

- BRCA1 in ependymoma (novel signal).

- SPIDR in high-grade glioma.

- SMC5 in medulloblastoma.

- SMARCAL1 in osteosarcoma — the most compelling and replicated finding.

| Discovery analysis: Novel associations | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene | Cancer | Frequency in Cases | Frequency in Controls | Cancer Risk | ||

| OR [95% CI] | Plogistic | FDRlogistic | ||||

| SMC5 | Medulloblastoma (MB) | 4 in 257 (1.56%) | 12 in 14477 (0.08%) | 21.6 [6.4 – 60.1] | 2.70E-07 | 4.87E-04 |

| SMARCAL1 | Osteosarcoma (OS) | 6 in 230 (2.61%) | 59 in 14477 (0.41%) | 6.3 [2.5 – 13.6] | 6.54E-05 | 0.019 |

| BRCA1 | Ependymoma (EPD) | 3 in 146 (2.05%) | 35 in 14477 (0.24%) | 11.6 [3.1 – 31.6] | 1.77E-04 | 0.037 |

| SPIDR | High grade glioma (HGG) | 2 in 206 (0.97%) | 6 in 14477 (0.04%) | 25.2 [4.5 – 101.1] | 1.91E-04 | 0.037 |

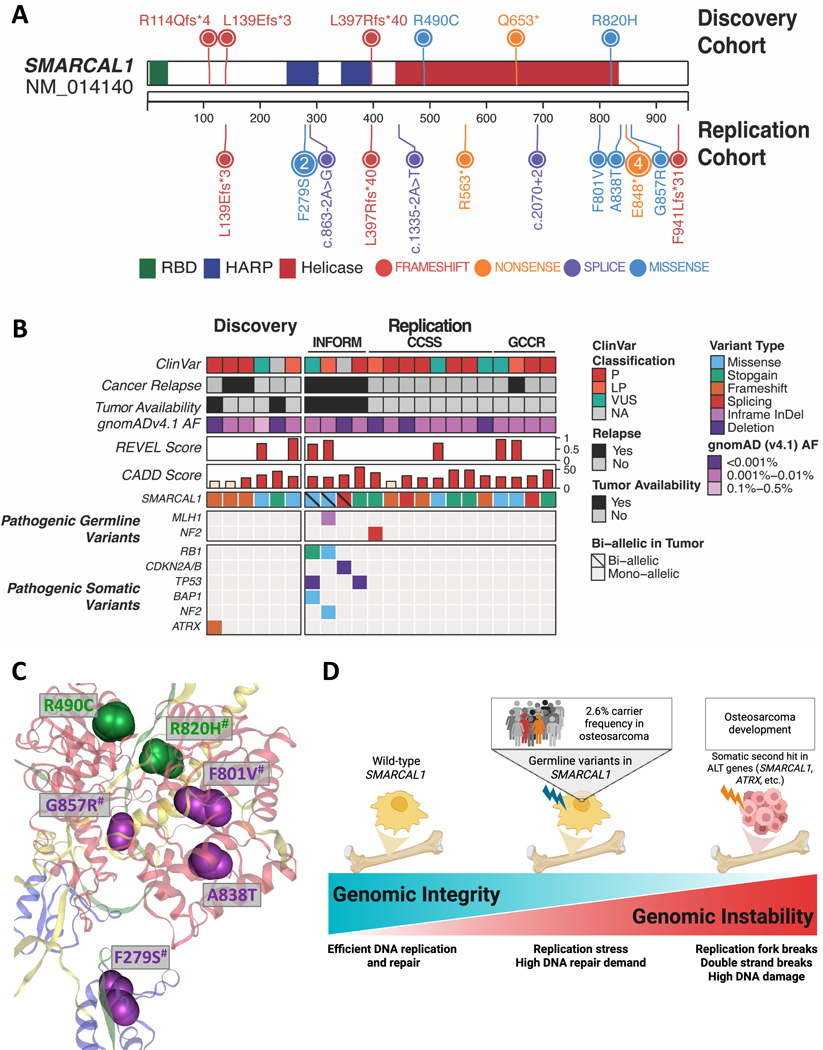

SMARCAL1 and osteosarcoma (detailed)

SMARCAL1 emerged as a replicated osteosarcoma predisposition gene. Key data points:

- Discovery cohort: 6/230 osteosarcoma cases (2.6%) carried germline SMARCAL1 PVs (FDR-adjusted logistic P = 0.0189).

- Three independent replication cohorts supported the association: CCSS (8/275, 2.9%; combined PFisher <.0001), CPS-GCCR (4/135, 3%, PFisher = .002), and ITRM/INFORM (4/217, 1.8%, PFisher = .012).<

- Tumor data: in three of four osteosarcoma tumors with available tumor sequencing, the remaining wild-type SMARCAL1 allele was deleted, consistent with a two-hit tumor suppressor model.

- These convergent lines of evidence (statistical enrichment across cohorts plus somatic loss of the wild-type allele in tumors) provide strong support for SMARCAL1 as a bona fide predisposition gene for osteosarcoma.

Figure 1. Germline DDR gene variants across pediatric cancers.

Biological plausibility and mechanistic insights

SMARCAL1 encodes an annealing helicase and replication fork remodeler that functions in the cellular response to replication stress. It participates in replication fork restart and protecting genome integrity during DNA replication. Germline biallelic loss-of-function variants in SMARCAL1 cause Schimke immuno-osseous dysplasia (SIOD), a rare recessive disorder with skeletal anomalies and immunodeficiency; heterozygous carrier phenotypes have been less well characterized. The observed pattern of germline truncating or deleterious variants combined with somatic deletion of the wild-type allele in tumors fits a classic tumor-suppressor mechanism (germline “first hit,” somatic loss as “second hit”). Given the central role of SMARCAL1 in replication stress management, its deficiency plausibly predisposes rapidly dividing osteogenic precursor cells to genomic instability and malignant transformation, which aligns biologically with osteosarcoma pathogenesis that often features complex structural rearrangements.

Figure 3: Characterization of SMARCAL1 predisposing variants.

Clinical implications

These findings have several practical implications for clinicians, genetic counselors, and researchers:

Genetic testing panels for pediatric cancer predisposition should consider including DDR gene sets, and specifically SMARCAL1 for patients with osteosarcoma, pending confirmatory studies and consensus guideline refinement.

For osteosarcoma patients found to carry SMARCAL1 PVs, tumor sequencing to assess for somatic second hits (eg, copy-number loss or LOH) can strengthen causal inference and may influence interpretation for patient management and family counseling.

Cascade testing of family members could identify at-risk relatives; however, clinical penetrance, age-dependent risk, and spectrum of SMARCAL1-associated tumors remain to be defined, so counseling should be cautious and framed around current uncertainty.

Therapeutic implications: DDR deficiency may open the door to targeted therapies (eg, PARP inhibitors or agents exploiting replication stress), but evidence for efficacy in SMARCAL1-deficient tumors is lacking and should be explored in preclinical models before adoption.

Expert commentary: strengths and limitations

Strengths of the study include the large multi-cohort discovery cohort, the focused gene set on DDR pathways, rigorous tiered variant classification, and replication in multiple independent pediatric cohorts. The analysis of tumor sequencing for somatic second hits adds mechanistic depth.

Limitations and cautionary notes:

Control group composition: adult noncancer controls were used in the discovery comparison, which may introduce age-related differences in variant frequency or survivorship effects. The authors mitigated this by replication among pediatric cohorts, but residual confounding by ancestry or technical factors remains possible.

Variant classification: despite a tiered approach, reliance on in silico tools and database annotations risks misclassification of rare variants. Functional validation and family segregation data are still needed for many alleles.

Penetrance and clinical expressivity: the absolute risk conferred by heterozygous SMARCAL1 PVs is not established. Reported carrier frequencies (~2–3% among osteosarcoma cases in the cohorts) suggest enrichment but do not directly provide lifetime risk estimates for carriers.

Heterogeneity of osteosarcoma: tumor histology, age at diagnosis, and prior therapies vary; whether SMARCAL1-associated osteosarcomas have distinct clinical behavior or therapy response requires further study.

Research and practice priorities going forward

Key next steps include:

- Functional studies to characterize the effects of specific SMARCAL1 germline variants on protein function, replication stress responses, and transformation efficiency in osteogenic lineage models.

- Family-based and population studies to estimate penetrance, age-specific risks, and tumor spectrum associated with heterozygous SMARCAL1 PVs.

- Registry efforts and prospective surveillance protocols for carriers to define natural history and inform evidence-based screening recommendations.

- Preclinical therapeutic work to test vulnerabilities associated with SMARCAL1 loss (eg, ATR inhibitors, replication stress–targeting agents, or synthetic lethal approaches) and careful clinical evaluation only after compelling preclinical data.

- Harmonization of test panels and reporting standards for DDR genes in pediatric oncology, including consideration of tumor-normal sequencing to identify somatic second hits.

Conclusion

The study by Oak et al. represents an important step in validating the role of DNA damage response gene variation in pediatric cancer predisposition and in identifying SMARCAL1 as a novel and replicated osteosarcoma predisposition gene. The combination of statistical enrichment across cohorts and somatic loss of the wild-type allele in tumors supports a tumor-suppressor model for SMARCAL1 in osteosarcoma. Clinicians should consider the implications for genetic testing and family counseling while recognizing that penetrance and management guidelines for SMARCAL1 carriers are not yet established. Further functional work, prospective natural history studies, and consensus guideline development will be essential to translate these findings into practice safely and effectively.

Funding and clinicaltrials.gov

Funding and trial registration information are reported in the original publication: Oak N et al., J Clin Oncol. 2025 Oct 9: JCO2501114. Please refer to the article for detailed funding statements and cohort-specific data sources.

References

Oak N, Chen W, Blake A, Harrison L, O’Brien M, Previti C, Balasubramanian G, Maass K, Hirsch S, Penkert J, Jones BC, Schramm K, Nathrath M, Pajtler KW, Jones DTW, Witt O, Dirksen U, Li J, Sapkota Y, Ness KK, Guenther LM, Pfister SM, Kratz C, Wang Z, Armstrong GT, Hudson MM, Wu G, Autry RJ, Nichols KE, Sharma R. Investigation of DNA Damage Response Genes Validates the Role of DNA Repair in Pediatric Cancer Risk and Identifies SMARCAL1 as a Novel Osteosarcoma Predisposition Gene. J Clin Oncol. 2025 Oct 9: JCO2501114. doi: 10.1200/JCO-25-01114