The Silent Epidemic: Understanding Spinal Cord Injuries

For decades, the medical community has viewed severe spinal cord injuries (SCI) as an irreversible sentence. When the delicate bundle of nerves that transmits signals between the brain and the body is severed or crushed, the result is often permanent paralysis. Unlike other tissues in the body, the central nervous system has a notoriously limited capacity for self-repair. Once neurons are disconnected, the body forms a glial scar—a dense biological barrier that prevents new axons from crossing the site of the injury. This physical and chemical wall turns a temporary trauma into a lifelong condition. However, a groundbreaking discovery from the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ) in Brazil is now challenging this scientific dogma. Led by Professor Tatiana Sampaio, a team of researchers has developed a therapeutic protein called Polylaminin. This compound has demonstrated a remarkable ability to bridge the gap in damaged spinal cords, allowing nerves to reconnect and restoring sensation and movement to patients who were once told they would never walk again.

A Visionary Discovery: From Placenta to Neural Pathways

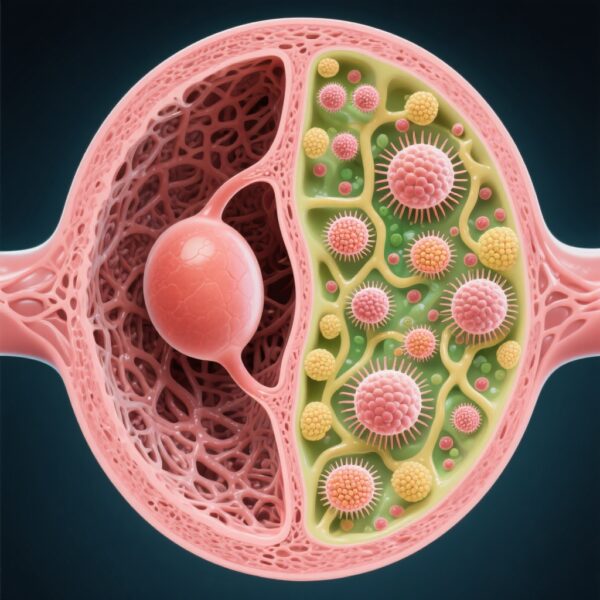

Professor Tatiana Sampaio, now 59, has dedicated nearly three decades to understanding the building blocks of human life. Her journey into neuro-regeneration began in 1997 when she first encountered laminin. Laminin is a naturally occurring protein in the extracellular matrix, most abundant during embryonic development. It acts as a guide, creating a complex web that helps neurons migrate and axons grow to form synapses. In the womb, laminin is the architect of the nervous system. After birth, however, the production of laminin drops sharply, leaving adults without the tools needed for neural repair. Sampaio’s breakthrough came when her lab discovered that under specific biochemical conditions, laminin could be polymerized into a more stable, larger structure: Polylaminin. This synthetic version mimics the embryonic environment, providing a three-dimensional scaffold that encourages axons to grow through the inhibitory environment of a spinal injury. To produce this protein safely and at scale, Sampaio’s team looked to a surprising source: the human placenta. Because the placenta is a biological byproduct of birth, it provides a rich, ethically sound source of laminin that can be processed into the therapeutic Polylaminin compound.

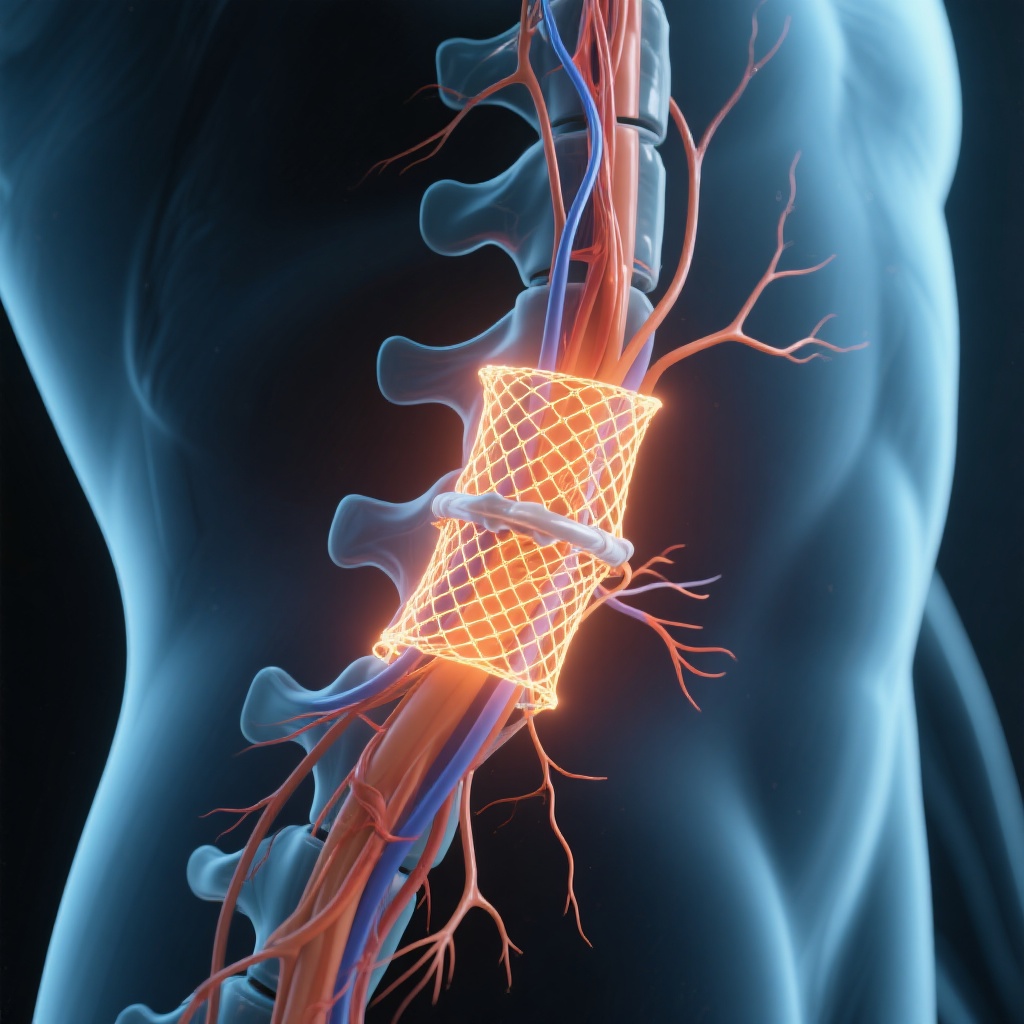

The Science of Connection: How Polylaminin Works

Polylaminin acts as both a biological glue and a structural bridge. When injected directly into the site of a spinal cord injury, it stabilizes the area and inhibits the formation of the obstructive glial scar. More importantly, it provides a physical pathway for surviving neurons to extend their axons. In animal models, specifically rats, the recovery was astonishing, with many regaining full mobility within weeks. In humans, the process is slower due to the greater distances nerves must travel, but the underlying mechanism remains the same. The treatment is most effective during the acute phase—within the first 72 hours of injury. During this critical window, the spinal cord is in a state of flux, and the introduction of Polylaminin can prevent the permanent ‘shutting down’ of neural pathways.

Patient Stories: When Paralysis Becomes Movement

The most compelling evidence for Polylaminin comes from the human stories behind the data. Consider the case of Mark Thompson (a name representing the typical demographic of such injuries), a 28-year-old who suffered a catastrophic neck injury during a sporting accident. Like many in his position, Mark was diagnosed with complete quadriplegia. In the clinical observations in Brazil, patients with similar injuries showed rapid improvement after receiving the injection. One patient, 37-year-old Luiz Fernando Mozer, reported feeling sensation in his lower limbs less than 48 hours after the injection. He regained the ability to contract muscles in his thighs and pelvic region almost immediately. Another remarkable case is Bruno Drummond de Freitas, a 31-year-old who was completely paralyzed from the neck down (C7 injury) following a car accident in 2018. After the treatment, Bruno underwent intensive rehabilitation and eventually achieved the unthinkable: he stood up and walked again. Out of the first eight patients treated under compassionate use protocols, six regained significant motor function, and one achieved total independence in walking. This 75% success rate stands in stark contrast to the standard clinical expectation of only 10% for similar injuries.

Scientific Evidence and Clinical Outcomes

The following table summarizes the observed differences between traditional recovery outcomes for complete spinal cord injuries and the results noted in the preliminary Polylaminin studies.

Comparison of Outcomes

Traditional Prognosis: Permanent loss of motor/sensory function below the injury site. Recovery rate for walking is under 10% for complete lesions. Glial scar prevents nerve regrowth. Polylaminin Observation: Sensation often returns within 48-72 hours. 75% of initial study group regained movement. Scaffold bypasses the scar and promotes axonal extension.

The Reality of Research: Funding and Patent Struggles

Despite the scientific triumph, the journey has been fraught with hardship. Professor Sampaio has spoken openly about the emotional and financial toll of the project. For years, her lab operated on a shoestring budget, supported by the Rio de Janeiro State Research Foundation (FAPERJ). At one point, she even stopped receiving her university salary to ensure the partnership with the pharmaceutical company Cristália could proceed. Perhaps the most heartbreaking aspect of the story is the loss of international patents. Due to government budget cuts in 2015 and 2016, the university was unable to pay international patent maintenance fees. As a result, while Brazil holds the intellectual property rights, the formula could theoretically be copied globally without protection. However, Sampaio remains focused on the mission rather than the profit. Her partnership with Cristália has ensured that the protein is manufactured to pharmaceutical standards, using placentas donated by healthy mothers who are screened for viruses during prenatal care.

The Regulatory Roadmap: Anvisa and the Future

The future for Polylaminin looks promising but requires rigorous validation. In January 2024, Anvisa (Brazil’s National Health Surveillance Agency) officially approved Phase I clinical trials. This phase will involve five volunteers between the ages of 18 and 72 who have suffered acute complete spinal cord injuries. The study will be conducted in hospitals across Rio de Janeiro, São Paulo, and Espírito Santo. If Phase I and subsequent phases are successful, Cristália aims to file for full registration by 2028. There is also a commitment to integrate the treatment into Brazil’s Unified Health System (SUS), potentially making the ‘miracle’ injection available for free to the public. It is important to note that the current research focuses strictly on acute injuries (less than 72 hours old). For those with chronic injuries where scarring has already solidified over months or years, Polylaminin is not yet a recommended solution, though researchers hope to explore chronic applications in the future.

Conclusion: A New Era for Regenerative Medicine

The story of Polylaminin is more than just a medical breakthrough; it is a testament to the persistence of scientists who refuse to accept ‘impossible’ as an answer. While the medical community awaits the peer-reviewed results of the formal clinical trials, the early evidence suggests that the era of permanent paralysis may finally be coming to an end. For millions around the world living with spinal cord injuries, Professor Sampaio’s work offers a beacon of hope—a chance to move, to feel, and to walk once again.