Highlights

– In a prospective multicenter cohort of 428 patients supported with ECMO in the Netherlands, 155 (36%) were alive at 5 years.

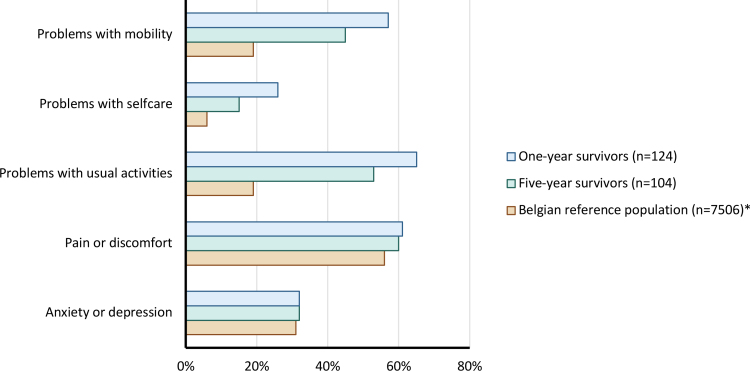

– Five-year survivors reported a median EQ-5D index of 0.82 (IQR 0.73–0.98), indicating overall satisfactory health-related quality of life (HRQoL) despite frequent ongoing problems: pain/discomfort (60%), impairment of usual activities (44%), and mobility limitations (39%).

– Employment status at 5 years: 41% employed, 31% retired, 26% permanently declared unfit for work; extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation (eCPR) had the lowest 5-year survival (25%).

Background

Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) is an established rescue therapy for patients with severe respiratory or cardiac failure that is refractory to conventional management. Use of ECMO has expanded over the last two decades, informed by randomized trials for severe acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) and by advances in technology and centralization of care. While short‑term survival and in-hospital outcomes are commonly reported, less is known about longer-term survivorship, health-related quality of life (HRQoL), functional status, and vocational outcomes among ECMO recipients. Long-term follow-up is essential to inform candidacy decisions, resource allocation, rehabilitation planning, and counseling of patients and families.

Study Design

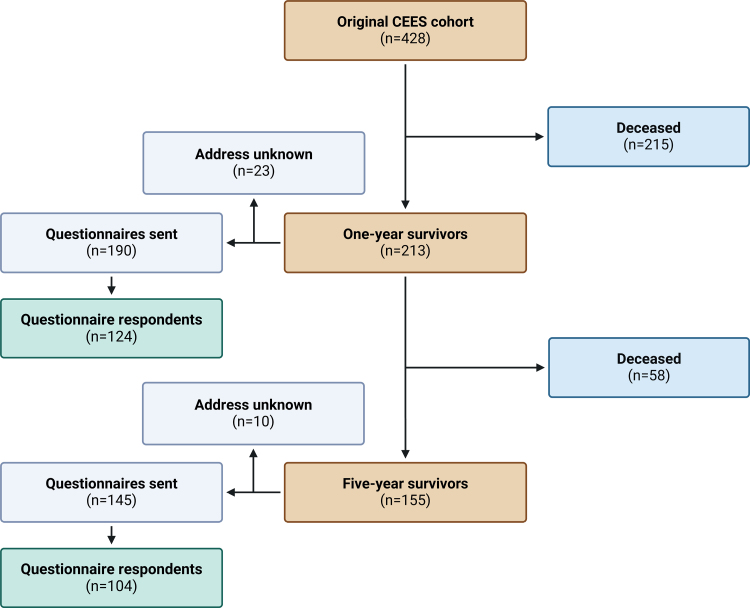

The Dutch Extracorporeal Life Support (ECLS) Study Group performed a prospective multicenter observational cohort follow-up study including consecutive adults supported with ECMO between August 2017 and July 2019 at ten Dutch ECMO centers (representing >90% of national ECMO volume). The primary objectives were to report 5-year survival and to measure HRQoL and occupational status among survivors.

Survival status at 5 years was obtained through linkage with the Dutch municipal records database. All surviving patients at 5 years were invited to complete standardized questionnaires: the EuroQol 5D Five Levels (EQ-5D-5L) instrument for HRQoL, and the Institute for Medical Technology Assessment Productivity Cost Questionnaire for occupational outcomes. No interventions were applied; this is an observational study (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT02837419).

Key Findings

Survival

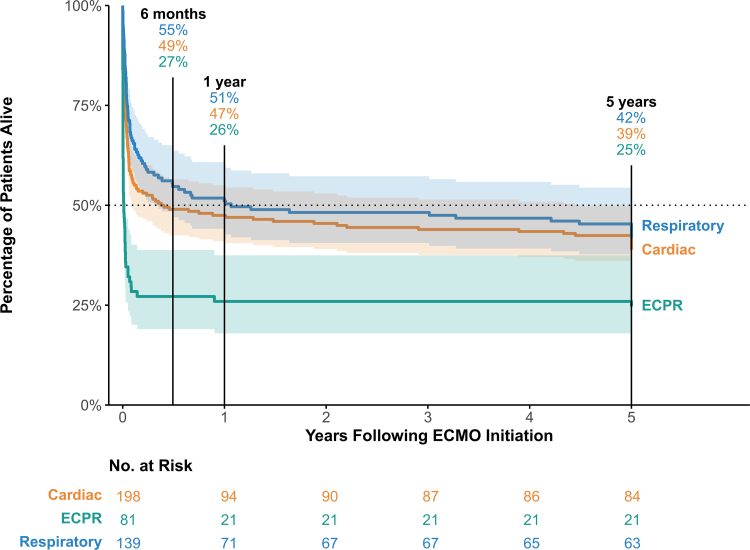

Of 428 patients who received ECMO during the enrollment window, 230 (54%) survived to hospital discharge, 213 (50%) survived to 1 year, and 155 (36%) were alive at 5 years. Five-year survival varied by indication: 42% for respiratory ECMO, 39% for cardiac ECMO, and 25% for extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation (eCPR). These data provide real-world, contemporary long-term survival estimates from a national, high-volume ECMO network.

Health-Related Quality of Life (HRQoL)

The response rate among five-year survivors was 72%. The median EQ-5D index score was 0.82 (interquartile range 0.73–0.98; scale anchored at 0 = dead, 1 = full health), which the investigators interpret as satisfactory HRQoL. Domain-specific responses revealed ongoing burden: 39% of respondents reported slight-to-moderate problems with mobility, 44% reported problems with usual activities (work, study, housework), and 60% reported pain or discomfort. Anxiety/depression was reported but not emphasized in the summary; detailed domain frequencies are available in the full text. These results imply that while overall perceived health is reasonable, many survivors experience persistent symptoms and functional limitations that affect daily life.

Occupational Status and Productivity

At 5 years, 41% of survivors were employed, 31% had retired (age or other reasons), and 26% were permanently declared unfit for work. These vocational outcomes highlight the socioeconomic impact of critical illness requiring ECMO and underscore the need for long-term post-ICU rehabilitation and vocational support programs.

Comparisons and Context

Five-year survival of 36% after ECMO is consistent with prior reports that show substantial early attrition with a plateau in longer-term survival among hospital survivors. The overall EQ-5D index reported here (median 0.82) is comparable to or slightly better than some cohorts of ARDS survivors at 5 years (e.g., long-term ARDS survivors often report persistent impairments despite survival) but remains lower than population norms in many countries. The high prevalence of pain and functional impairment aligns with broader literature on post‑critical illness sequelae, including ICU-acquired weakness, chronic pain syndromes, and neuropsychological impairment.

Expert Commentary and Interpretation

This study provides one of the most complete national pictures of long-term outcomes after ECMO, leveraging near-complete survival ascertainment and standardized patient-reported outcome measures. Important clinical messages include:

– ECMO can be associated with meaningful 5-year survival across indications, including respiratory and cardiac failure, supporting its use in appropriately selected patients.

– Survivors often experience ongoing impairments that are not captured by survival metrics alone; pain and limitations in mobility and usual activities are common and clinically important.

– A substantial minority of survivors do not return to work and are declared unfit for employment, with implications for patients, caregivers, and health systems.

Biological and Mechanistic Considerations

Persistent symptoms after ECMO likely reflect multiple mechanisms: the underlying disease (eg, severe lung injury, cardiac arrest), organ dysfunction accrued during critical illness, deconditioning and muscle wasting, neuropathy, long-term organ-specific sequelae (e.g., fibrotic lung disease), and psychological distress. ECMO itself may attenuate organ injury by enabling lung-protective ventilation or supporting recovery after cardiac arrest, but it also exposes patients to anticoagulation-related complications, infection risk, and potential inflammatory responses that can influence recovery trajectories.

Limitations and Generalizability

Caveats when interpreting results:

– The cohort represents high-volume Dutch ECMO centers and the pre-COVID-19 era (last enrollments July 2019), so findings may not generalize to centers with different volume, patient selection, or to patients receiving ECMO during the COVID-19 pandemic.

– As an observational study without a non‑ECMO comparator, causal inferences about the effect of ECMO on long-term outcomes cannot be made.

– Response bias is possible: although the questionnaire response rate among survivors was good (72%), nonresponders may have worse or better HRQoL, biasing results.

– Baseline HRQoL prior to illness was not reported in the abstract; without baseline measurement, interpreting change from premorbid function is limited.

– Patient-reported HRQoL provides essential insight but lacks objective functional measures (e.g., 6-minute walk distance, pulmonary function tests) that would complement the assessment.

These limitations do not diminish the study’s value but frame how the results should be used in clinical decision-making and policy.

Implications for Practice and Policy

For clinicians and health systems, the study supports the following practical points:

– Discuss long-term prognosis with patients and families, emphasizing that a substantial fraction survive to 5 years with generally satisfactory perceived health, but many have ongoing symptoms that require follow-up.

– Establish or strengthen post-ICU/ECMO follow-up clinics that provide multidisciplinary assessment (physical rehabilitation, pain management, mental health support, vocational rehabilitation) to address common needs highlighted by this cohort.

– Use long-term outcome data for shared decision-making and in developing criteria for ECMO candidacy that consider likely survivorship and potential for meaningful recovery.

– Health policy-makers should account for the persistent rehabilitation and social support needs of ECMO survivors when planning services and budgets.

Conclusion

In this large, prospective national cohort from the Netherlands, ECMO was associated with a 36% five-year survival. Survivors reported satisfactory overall HRQoL by EQ-5D index but a high prevalence of persistent pain, mobility limitations, and decreased ability to perform usual activities, and more than one quarter were permanently unfit for work. These findings highlight that long-term survivorship after ECMO is realistic, yet many patients continue to require support for physical and social recovery. Future research should explore interventions to reduce long-term symptom burden, optimal models for post-ECMO follow-up, and comparative outcomes in more diverse healthcare settings including the COVID-19 era.

Funding and ClinicalTrials.gov

Trial registration: ClinicalTrials.gov NCT02837419. Funding details are reported in the original publication (Jolink et al., Crit Care Med 2025).

References

1. Jolink FEJ, Onrust M, Dos Reis Miranda D, et al.; Dutch Extracorporeal Life Support (ECLS) Study Group. Five Years After Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation: A Prospective Cohort Study of Health-Related Quality of Life and Patient Outcomes. Crit Care Med. 2025 Dec 1;53(12):e2487-e2496. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000006900 IF: 6.0 Q1 . PMID: 41091003 IF: 6.0 Q1 .

2. Peek GJ, Mugford M, Tiruvoipati R, et al.; CESAR trial collaboration. Efficacy and economic assessment of conventional ventilatory support versus extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for severe adult respiratory failure (CESAR): a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2009;374(9698):1351–1363.

3. Combes A, Hajage D, Capellier G, et al.; EOLIA Trial Group. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for severe acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(21):1965–1975.

4. Herridge MS, Cheung AM, Tansey CM, et al. One-year outcomes in survivors of the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(8):683–693. (Classic long-term ARDS outcomes literature; for extended follow-up see subsequent Herridge et al. studies on multi-year outcomes.)

5. Needham DM, Davidson J, Cohen H, et al. Improving long-term outcomes after discharge from intensive care unit: report from a stakeholders’ conference. Crit Care Med. 2012;40(2):502–509.