Highlight

– A large Ontario population cohort of Chinese immigrants found early-life exposure to the Great Chinese Famine was associated with substantially higher incidence of type 2 diabetes (T2D) and modestly higher incidence of hypertension.

– Associations were strongest for prenatal exposure and remained elevated for childhood and adolescent exposure for T2D; cardiovascular hospitalizations were not increased and were lower after adolescent exposure.

– Prior meta-analytic work cautions that age differences between exposure and comparison groups can inflate famine effect estimates; rigorous age-balanced designs and improved famine-intensity measures are needed.

Background

The Developmental Origins of Health and Disease (DOHaD) paradigm posits that environmental influences during critical windows of prenatal and early postnatal life permanently shape organ structure and metabolic regulation, altering adult cardiometabolic risk. Classic population studies, such as those by Barker and colleagues, linked markers of early-life undernutrition to later coronary heart disease and metabolic disease. Natural experiments — most notably famines — have been used to test these ideas in humans. Several reports from the Chinese famine of 1959–1961 and the Dutch Hunger Winter have suggested increased adult diabetes, hypertension, and other cardiometabolic conditions after prenatal famine exposure. However, methodological differences across studies, particularly the selection of control birth cohorts and the handling of age differences, have produced heterogeneous results and raised concerns about bias.

Study design (Cao et al., JAMA Netw Open 2025)

Population and setting

Cao and colleagues performed a population-based cohort analysis using administrative health data from Ontario, Canada, to study Chinese immigrants in three parallel cohorts assembled for the coprimary outcomes: incident T2D, incident hypertension, and cardiovascular hospitalization. Adults aged 20–85 years who lived in Ontario between April 1, 1992, and March 31, 2019, were included; follow-up extended until age 85, relocation from Ontario, or March 31, 2023.

Exposure classification

Early-life exposure to the Great Chinese Famine was defined by year of birth (exposed group 1941–1952 in the paper; comparison groups were those born before 1941 or after 1962). The authors categorized exposure windows as prenatal, childhood, or adolescent based on year-of-birth strata corresponding to likely timing of famine exposure.

Outcomes

Coprimary outcomes were incident type 2 diabetes, incident hypertension, and cardiovascular hospitalization (all defined using validated administrative algorithms). Participants were followed for incident events and hazards were estimated using time-to-event models, adjusted for available covariates.

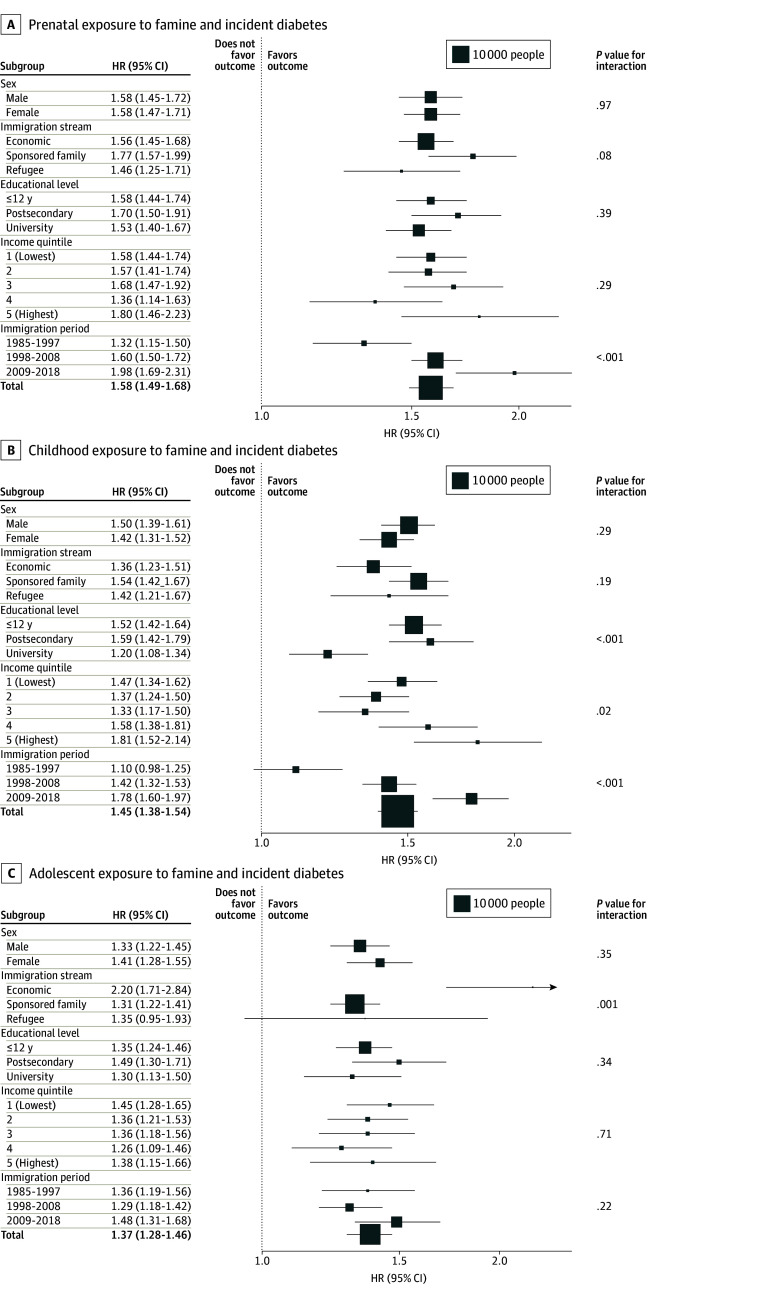

Figure 1. Associations of Prenatal, Childhood, and Adolescent Exposures to Famine With Incidence of Type 2 Diabetes.

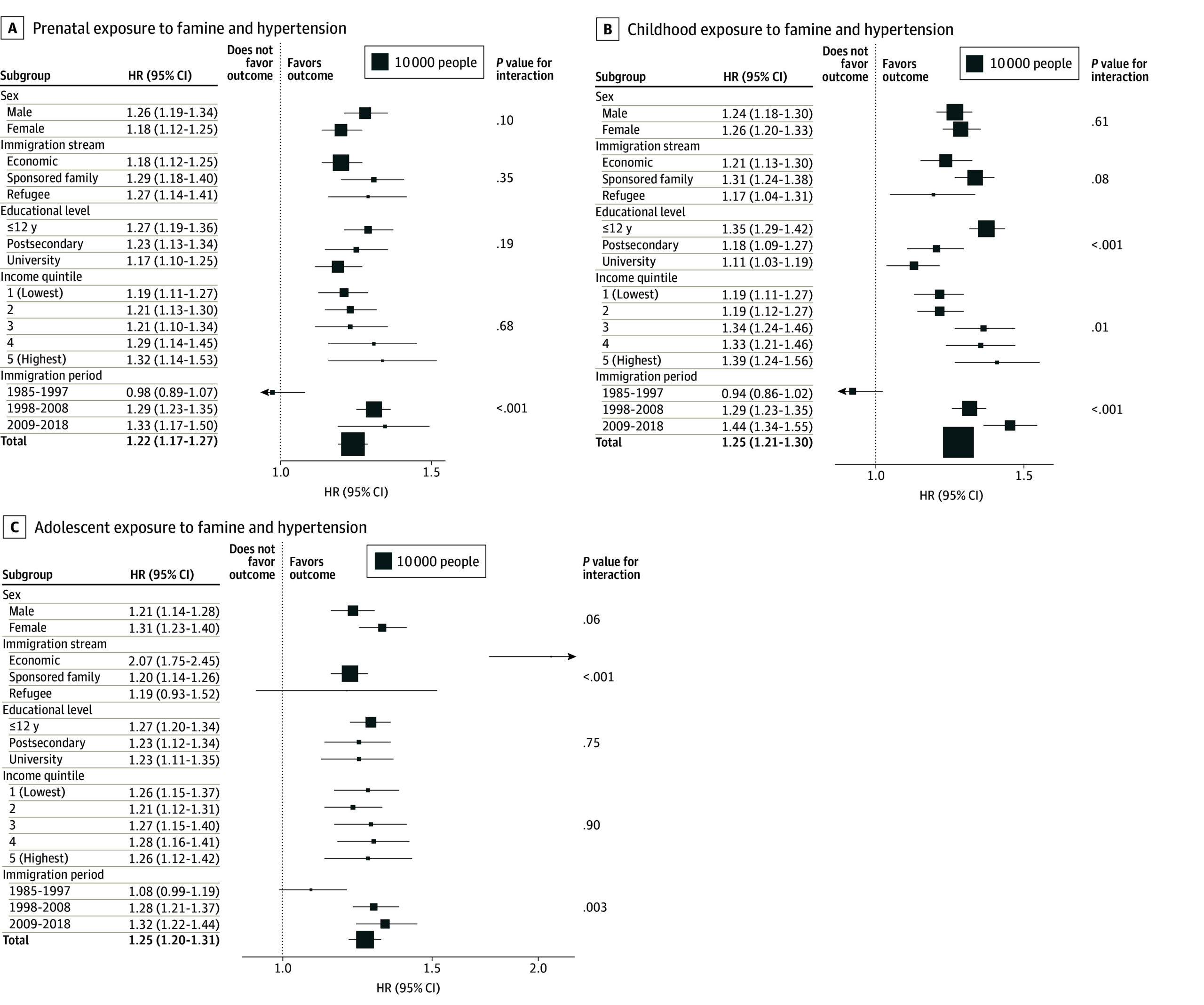

Figure 2. Associations of Prenatal, Childhood, and Adolescent Exposures to Famine With Incidence of Hypertension.

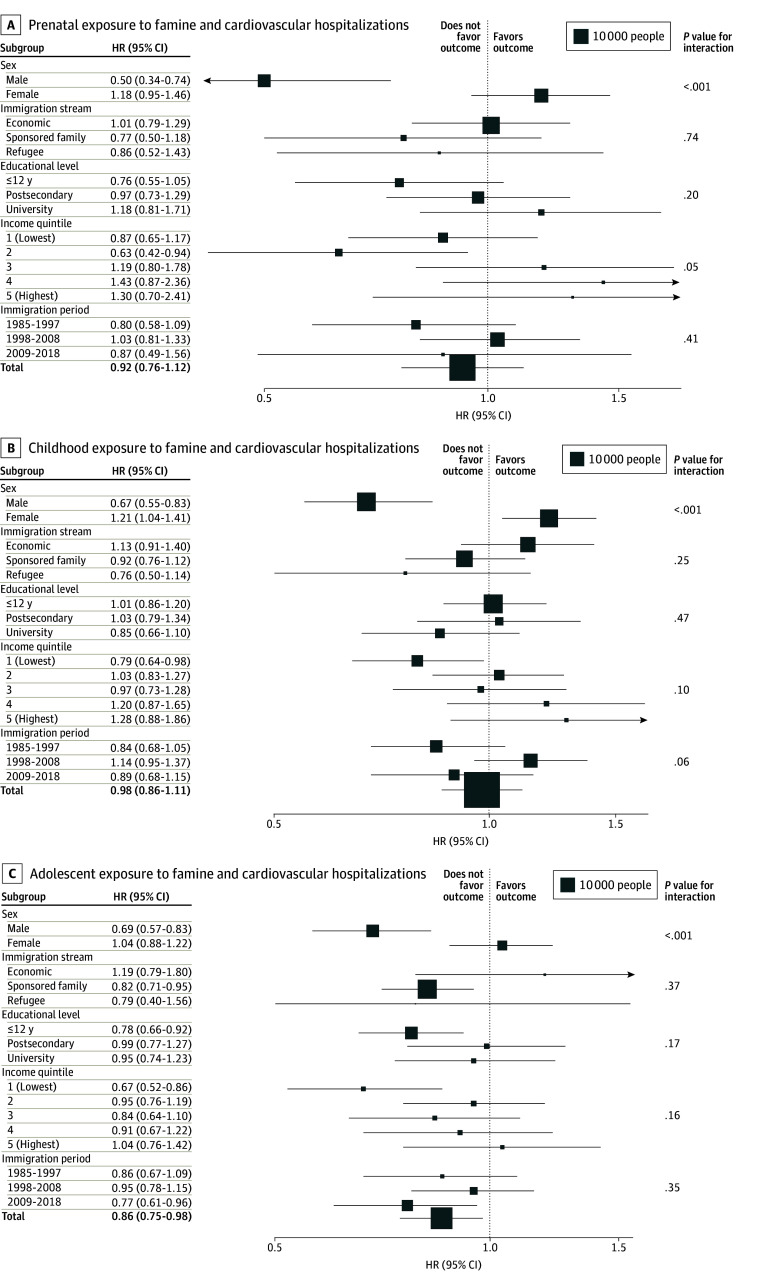

Figure 3. Associations of Prenatal, Childhood, and Adolescent Exposures to Famine With Incidence of Cardiovascular Hospitalization.

Key findings

The cohort sizes were large: the T2D cohort included 188,292 individuals; the hypertension cohort included 180,510; and the cardiovascular hospitalization cohort included 208,921. Baseline characteristics differed by exposure group, with exposed groups older on average than unexposed groups.

Event rates

Among famine-exposed individuals the event rates were: T2D 13.6%; hypertension 29.8%; cardiovascular hospitalization 1.6%.

Type 2 diabetes

Early-life famine exposure was associated with substantially increased hazards of incident T2D. Reported adjusted hazard ratios (HRs) compared with the unexposed group were: prenatal HR 1.58 (95% CI, 1.49–1.68); childhood HR 1.45 (95% CI, 1.38–1.54); adolescent HR 1.37 (95% CI, 1.28–1.46). These represent large relative increases in risk and consistent elevation across exposure windows, greatest with prenatal exposure.

Hypertension

Early-life famine exposure was associated with modestly higher hazards of incident hypertension. Adjusted HRs were: prenatal HR 1.22 (95% CI, 1.17–1.27); childhood HR 1.25 (95% CI, 1.21–1.30); adolescent HR 1.25 (95% CI, 1.20–1.31). Effect sizes were smaller than for T2D but statistically robust.

Cardiovascular hospitalization

By contrast, prenatal and childhood famine exposure were not associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular hospitalization (prenatal HR 0.92 [95% CI, 0.76–1.12]; childhood HR 0.98 [95% CI, 0.86–1.11]). Interestingly, adolescent exposure was associated with a modestly lower risk of cardiovascular hospitalization (HR 0.86, 95% CI, 0.75–0.98).

Interpretation and clinical implications

The Ontario immigrant cohort study provides compelling population-level evidence that severe early-life undernutrition is associated with higher risks of adult T2D and hypertension even after migration to a high-income setting. The gradient of risk (prenatal > childhood > adolescent for T2D) aligns with DOHaD expectations that prenatal life is a highly sensitive window for programming metabolic pathways. These findings underscore the importance of considering an individual’s birth cohort and early-life history when assessing cardiometabolic risk, particularly in immigrant populations from regions that experienced severe historical famine.

Mechanistic plausibility

Proposed mechanisms include impaired pancreatic beta-cell development, altered nephron endowment and vascular structure, epigenetic modifications affecting energy metabolism and insulin signaling, and accelerated postnatal catch-up growth that promotes adiposity and insulin resistance when caloric abundance follows early restriction. These pathways are supported by animal models and human cohort work in other famine settings.

Contextualizing with prior evidence and methodological caveats

Not all previous studies agree about the magnitude — or even the direction — of famine effects on later T2D. A 2022 systematic review and meta-analysis by Li and Lumey (Nutrients 2022) of 23 studies found that effect estimates varied substantially depending on the choice of comparison births. Using postfamine births alone as controls (a common approach) produced a pooled OR of 1.50 (95% CI, 1.34–1.68) for T2D among famine births, but using combined prefamine and postfamine births reduced the estimate to OR 1.12 (95% CI, 1.02–1.24), and using prefamine births alone yielded OR 0.89 (95% CI, 0.79–1.00). Crucially, their meta-regression showed that unaccounted age differences between exposed and control groups inflated effect estimates: each additional ignored year of age difference increased estimated famine effects by roughly 5% or more.

These methodological insights matter for interpreting the Ontario immigrant study. The reported exposed groups were older on average than unexposed groups, which can confound incidence comparisons unless age is very precisely modeled. Administrative data allow robust ascertainment of outcomes but may lack granular covariates (early-life socioeconomic status, famine intensity at place of birth, nutritional measures, smoking, body mass index trajectories, and timing of migration) that could confound or mediate observed associations.

Strengths and limitations of the Ontario immigrant analysis

Strengths

– Large, population-based sample of immigrants with long follow-up and validated outcome ascertainment using administrative data.

– Focus on emigrants provides novel insight into how early undernutrition effects persist after transition to nutrient-rich environments.

– Consistent patterns across exposure windows and two cardiometabolic endpoints support biological plausibility.

Limitations

– Potential residual confounding by age, socioeconomic factors, and migration-related exposures. Although statistical models adjust for measured confounders, unmeasured early-life and life-course exposures may influence results.

– Exposure misclassification: defining famine exposure by birth year alone cannot capture variation in famine intensity by region, household, or maternal nutritional status.

– Generalizability: findings relate to Chinese immigrants to Ontario and may not apply to those who remained in China or to other immigrant groups.

– The paradoxical lower cardiovascular hospitalization risk after adolescent exposure is difficult to interpret and may reflect survivor bias, competing risks, differential health care use, or chance; it requires further study.

Clinical and public-health takeaways

For clinicians caring for middle-aged and older immigrants from regions affected by severe historical famine, a history of birth during the famine period should prompt heightened vigilance for T2D and hypertension. This could justify earlier or more frequent screening, lifestyle counseling, and risk-factor control. From a public-health perspective, early-life undernutrition must be recognized as a population-level social determinant of cardiometabolic disease that contributes to disease burden in receiving high-income countries.

Research directions

Future work should aim to reduce bias and clarify mechanisms. Priority studies include age-balanced designs and sibling-comparison analyses, better measures of famine intensity at the community or household level, linkage to anthropometric and biomarker data (for epigenetic signatures, insulin secretion/resistance measures), and longitudinal data on postmigration lifestyle and weight trajectories. Interventional research could test whether early, aggressive cardiometabolic risk modification in famine-exposed individuals mitigates long-term risk.

Conclusion

The Cao et al. cohort provides strong evidence that early-life exposure to the Great Chinese Famine is an important predictor of later-life type 2 diabetes and hypertension among Chinese immigrants in Ontario. These findings extend DOHaD insights to migrant populations and reinforce the need to incorporate early-life history into clinical risk assessment and public-health planning. However, methodological challenges identified in prior meta-analyses—especially the impact of age differences between exposed and comparison groups and imprecise famine exposure metrics—remain critical to address in future research.

Funding and clinicaltrials.gov

Funding and trial registration details are reported in the original publications. See Cao et al., JAMA Netw Open (2025) and Li & Lumey, Nutrients (2022) for specific disclosures.

References

1. Cao A, Hong Z, Liu N, Xiao J, Lee DS, Ke C; Cardiovascular-Metabolic Disease In Asian Populations Relocated Abroad (CV-DIASPORA) Investigators. Early Life Exposure to the Great Chinese Famine and Cardiometabolic Outcomes. JAMA Netw Open. 2025 Nov 3;8(11):e2545444. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2025.45444 IF: 9.7 Q1 .

2. Li C, Lumey LH. Early-Life Exposure to the Chinese Famine of 1959-1961 and Type 2 Diabetes in Adulthood: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients. 2022 Jul 12;14(14):2855. doi:10.3390/nu14142855 IF: 5.0 Q1 .

3. Barker DJP, Osmond C. Infant mortality, childhood nutrition, and ischaemic heart disease in England and Wales. Lancet. 1986;1(8489):1077–1081.

4. Barker DJP. The fetal and infant origins of adult disease. BMJ. 1990 Nov 17;301(6761):1111.

5. Gluckman PD, Hanson MA. Developmental origins of disease paradigm: a mechanistic and evolutionary perspective. Pediatr Res. 2004;56(3):311–317.