Overview of Post-LAAC Antithrombotic Management

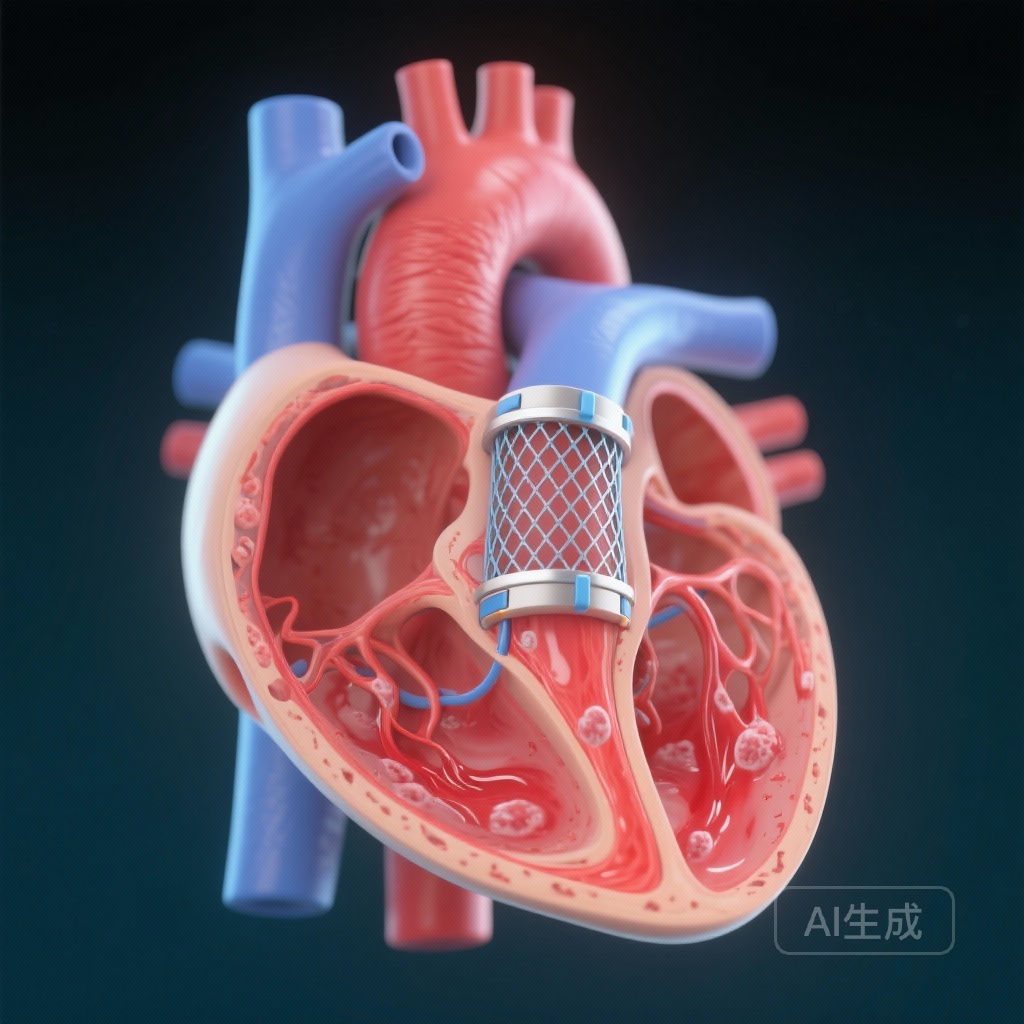

Transcatheter left atrial appendage closure (LAAC) has emerged as a cornerstone therapy for patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation (AF) who are at high risk for thromboembolic events but have contraindications or a strong preference against long-term oral anticoagulation. While the procedure successfully isolates the primary source of thrombi in AF, the immediate post-procedural period presents a unique clinical challenge: preventing device-related thrombosis (DRT) while the device undergoes endothelialization. Traditionally, antithrombotic regimens have varied significantly between institutions, ranging from warfarin or direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) to dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT).

The optimal strategy to balance the risk of DRT against the risk of post-procedural bleeding has remained a subject of intense debate. DRT is associated with a significantly increased risk of systemic embolism and stroke, yet the patient population undergoing LAAC is often characterized by advanced age and high baseline bleeding risk. The ANDES Randomized Clinical Trial was designed to provide much-needed evidence by directly comparing these two common strategies.

Highlights

The study provides several key insights for clinical practice:

- DOAC therapy for 60 days post-LAAC did not significantly reduce the incidence of device-related thrombosis (DRT) compared to DAPT (1.5% vs 4.1%, P=0.110).

- DOAC therapy demonstrated a superior safety profile, significantly reducing the composite safety outcome (22.5% vs 34.9%, P=0.003).

- The safety benefit was primarily driven by a lower rate of clinically relevant bleeding events in the DOAC group compared to the DAPT group.

- The findings suggest that for patients capable of tolerating short-term anticoagulation, DOACs may offer a safer transition period than DAPT during the device endothelialization phase.

The ANDES Trial: Study Design and Methodology

The ANDES (Short-Term Anticoagulation Versus Dual Antiplatelet Therapy for Preventing Device Thrombosis Following Left Atrial Appendage Closure) trial was a prospective, multicenter, international randomized controlled trial. It included 510 patients with nonvalvular AF who underwent successful LAAC. The participants had a mean age of 77 years, reflecting the typical high-risk, elderly population encountered in clinical practice. Of the total cohort, 35% were women.

Patients were randomized in a 1:1 ratio to receive one of two 60-day regimens:

- DOAC Group: Administration of a direct oral anticoagulant (such as apixaban, rivaroxaban, or edoxaban) for 60 days.

- DAPT Group: Administration of aspirin plus clopidogrel for 60 days.

The primary efficacy endpoint was the presence of DRT, as determined by transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) at the 60-day mark. To ensure objectivity, all TEE images were analyzed by a central core laboratory blinded to the treatment allocation. The safety outcome was a composite of all-cause mortality, stroke, bleeding, or site-reported DRT within the 60-day follow-up period, analyzed on an intention-to-treat basis.

Comparative Efficacy: Device-Related Thrombosis Outcomes

In the per-protocol analysis involving 399 patients who completed the 60-day TEE and adhered to their assigned medication, the primary outcome of DRT occurred in 3 patients (1.5%) in the DOAC group and 8 patients (4.1%) in the DAPT group. Although the numerical incidence of DRT was lower in the DOAC group, the difference of -2.7% (95% CI, -6.0% to 0.6%) did not reach statistical significance (P=0.110).

It is important to note that the overall incidence of DRT was relatively low in both groups compared to some historical registries, which may have impacted the trial’s ability to detect a statistically significant difference. The study authors noted that the narrower-than-expected difference between the groups suggests that while DOACs are effective, they do not provide a massive reduction in DRT over DAPT in this specific timeframe.

Safety and Bleeding: The Defining Difference

While efficacy outcomes were comparable, the safety data revealed a striking divergence between the two regimens. The composite safety outcome occurred in 22.5% of the DOAC group compared to 34.9% of the DAPT group. This absolute difference of 12.4% (95% CI, -20.6% to -4.2%) was highly significant (P=0.003).

This safety benefit was predominantly attributed to a reduction in bleeding events. Bleeding occurred in 17.4% of the DOAC group versus 24.9% in the DAPT group (P=0.038). This finding challenges the common clinical assumption that DAPT is inherently “safer” or carries a lower bleeding risk than DOAC therapy in the elderly. In the context of post-LAAC care, where the vascular access site and the patient’s underlying comorbidities (such as gastrointestinal fragility) are factors, the DOAC regimen proved more tolerable.

Expert Commentary and Clinical Interpretation

The results of the ANDES trial offer a nuanced perspective on post-LAAC pharmacotherapy. Historically, many clinicians opted for DAPT because of the perceived lower risk of major systemic bleeding compared to anticoagulants. However, ANDES suggests that short-term DOAC therapy is not only viable but potentially preferable from a safety standpoint.

The mechanism behind the higher bleeding rates in the DAPT group may be related to the synergistic effect of aspirin and clopidogrel on platelet inhibition, which can be particularly detrimental to the gastric mucosa in an elderly population. Conversely, DOACs provide targeted inhibition of Factor Xa or thrombin with a more predictable pharmacodynamic profile.

Study Limitations and Power Considerations

A critical point of discussion in the ANDES trial is statistical power. The study failed to prove the superiority of DOACs in reducing DRT, but the authors cautioned that this might be due to a lack of power rather than a lack of efficacy difference. The observed 2.7% difference, if confirmed in a larger cohort, would be clinically meaningful. Furthermore, the high rate of safety events in the DAPT group suggests that the ‘default’ choice of antiplatelets should be reconsidered.

Conclusions and Clinical Takeaways

The ANDES trial concludes that while DOAC therapy does not significantly reduce the incidence of device-related thrombosis compared to DAPT within the first 60 days following LAAC, it is associated with a significantly improved safety profile. For clinicians, this means that for patients who do not have an absolute contraindication to short-term anticoagulation, DOACs should be considered a first-line option to bridge the period until endothelialization is complete.

The findings emphasize the need for individualized therapy. While the safety benefit of DOACs is clear, larger trials are still required to definitively determine if one regimen is truly superior in preventing the rare but serious complication of DRT. Until then, the reduction in bleeding seen in the ANDES trial provides a compelling argument for the use of DOACs in the immediate post-LAAC period.

Funding and Registration

The ANDES trial was supported by various academic and clinical research grants. It is registered at ClinicalTrials.gov with the unique identifier: NCT03568890.

References

- Rodés-Cabau J, Nombela-Franco L, Cruz-Gonzalez I, et al. Short-Term Anticoagulation Versus Dual Antiplatelet Therapy for Preventing Device Thrombosis Following Left Atrial Appendage Closure: The ANDES Randomized Clinical Trial. Circulation. 2025;152(25):1759-1768. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.125.077469.

- Holmes DR Jr, Reddy VY, Turi ZG, et al. Percutaneous left atrial appendage closure vs warfarin therapy for atrial fibrillation: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2009;302(17):1889-1895.

- Dukkipati SR, Kar S, Holmes DR, et al. Device-Related Thrombus After Left Atrial Appendage Closure: Incidence, Predictors, and Outcomes. Circulation. 2018;138(9):874-885.