Highlights

– In a randomized, double‑blind crossover trial (n=23), a 200‑mL blackcurrant beverage delivering 711 mg anthocyanins produced a cumulative improvement in brachial artery flow‑mediated dilation (FMD) over 6 h after a high‑fat meal versus a matched placebo (iAUC difference 5.75 ± 1.32; P=0.014).

– The intervention reduced ex vivo ADP‑ and collagen‑induced platelet aggregation across the postprandial period (substantial iAUC reductions; P<0.01), and blunted a postprandial rise in plasma IL‑8 (iAUC difference −1826.8 ± 618.6; P=0.015, exploratory).

– Parent anthocyanins were not detectable in plasma; specific phenolic metabolites (hippuric acid, isovanillic acid, isoferulic acid glucuronide) correlated with vascular and blood pressure responses, suggesting microbial and hepatic biotransformation mediates bioactivity.

Study background and disease burden

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) remains the leading cause of morbidity and mortality globally. Postprandial metabolic and vascular perturbations after high‑fat meals contribute to endothelial dysfunction, transient increases in blood pressure, platelet activation, and low‑grade inflammation — mechanisms implicated in atherothrombosis. Dietary polyphenols, and specifically anthocyanins abundant in berries, have been associated epidemiologically with lower CVD risk, but high‑quality mechanistic human data are limited. Acute interventions that probe a vascular challenge (e.g., a high‑fat meal) are useful to test whether dietary components can mitigate transient, potentially atherogenic postprandial changes.

Study design

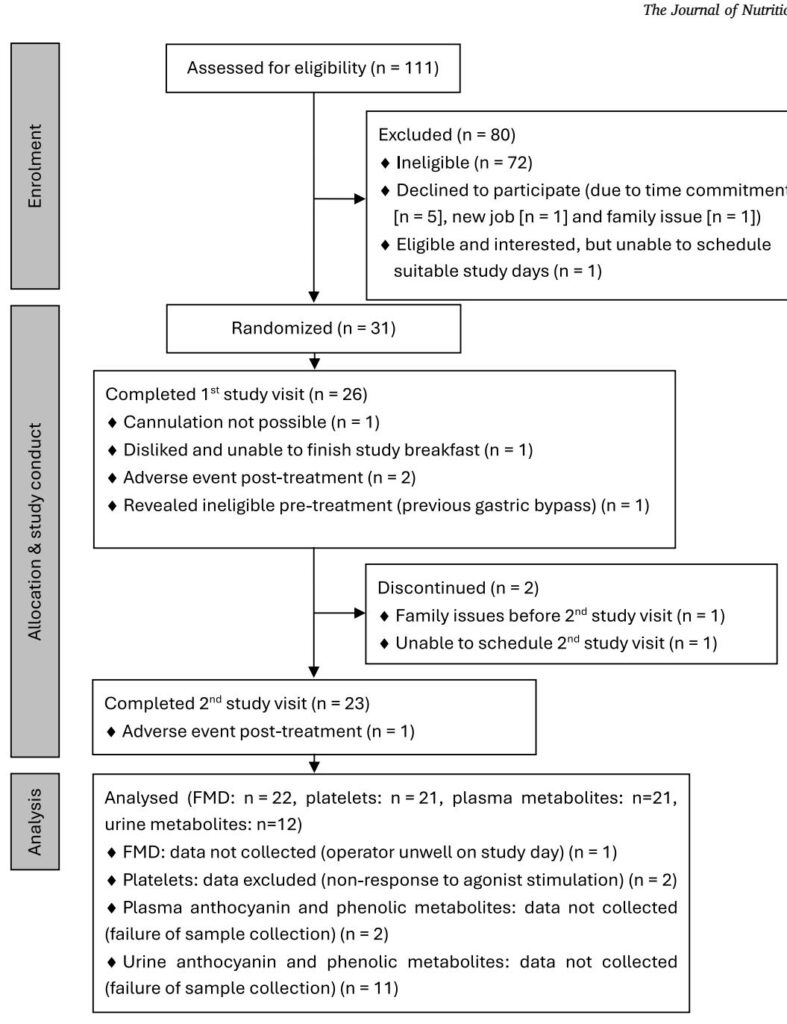

This was a randomized, double‑blind, placebo‑controlled 2‑period crossover study conducted at the University of Reading (clinicaltrials.gov NCT02459756). Twenty‑three healthy non‑smoking adults (mean age ~39.9 ± 8.1 y; BMI 22.9 ± 2.3 kg/m2; 11 female) completed both interventions separated by washouts (≥3 wk for men, 4 wk for women to partly control for cycle effects).

Interventions (single‑dose, given with a standardized high‑fat breakfast and a mid‑day lunch at 3 h):

- Blackcurrant beverage: 200 mL containing 744 mg total polyphenols (711 mg anthocyanins; principal species delphinidin‑3‑O‑rutinoside and cyanidin‑3‑O‑rutinoside).

- Placebo beverage: matched for sugars, acids, vitamin C, color/flavour but devoid of polyphenols.

Primary endpoints: brachial artery flow‑mediated dilation (FMD) and ex vivo agonist‑induced platelet aggregation. Secondary/exploratory endpoints included systolic and diastolic blood pressure (BP), digital volume pulse measures (DVP‑SI, DVP‑RI), circulating endothelial‑ and platelet‑derived extracellular vesicles (EDEVs/PDEVs), plasma interleukin‑8 (IL‑8), and plasma/urinary anthocyanin metabolites. Repeated measures were obtained up to 6 h postprandially (with a 24 h plasma/urine collection for metabolites).

Key findings

Vascular function (FMD)

– There was a significant cumulative improvement in FMD following the blackcurrant beverage across the 6‑hour postprandial window compared with placebo (incremental AUC difference 5.75 ± 1.32; 95% CI 2.99–8.51; P=0.014). The mixed model showed significant main effects of treatment and time but no treatment×time interaction, indicating an overall greater FMD response over the postprandial period with blackcurrant.

Platelet aggregation

– The blackcurrant beverage produced a consistent inhibitory effect on ex vivo platelet aggregation induced by ADP (10 μM and 100 μM) and collagen (0.5 and 1 μg/mL). Significant reductions in iAUCs were observed (e.g., ADP 10 μM iAUC difference −30.8 ± 8.7; P<0.01; ADP 100 μM −18.6 ± 4.1; P<0.001). These findings suggest an antiplatelet effect over the postprandial period.

Inflammation and blood pressure

– Plasma IL‑8: The usual postprandial rise in IL‑8 observed with the placebo was absent after the blackcurrant beverage (iAUC difference −1826.8 ± 618.6; P=0.015, exploratory).

– Systolic BP showed a treatment main effect in the mixed model (P=0.015 unadjusted), although the incremental AUC difference for SBP did not reach statistical significance. Diastolic BP showed a trend (P≈0.054). These BP analyses were exploratory and not corrected for multiple comparisons.

Extracellular vesicles and arterial stiffness

– No significant differences were found for DVP‑SI (large artery stiffness), DVP‑RI (reflection index), or circulating EDEVs/PDEVs between treatments in this healthy cohort.

Metabolomics and metabolite–phenotype associations

– Parent anthocyanins were not detected in plasma, consistent with rapid metabolism. Plasma total phenolics peaked at ~2–4 h post‑dose (~3.1 ± 0.14 μM over 24 h). Specific plasma metabolites (vanillic acid, isovanillic acid, ferulic acid glucuronide, isoferulic acid glucuronide, cyanidin glucuronide) increased after blackcurrant consumption. Urinary excretion of select phenolics rose in the 0–6 h window.

– Multivariate models identified plasma isovanillic acid and hippuric acid as independent predictors of FMD, jointly explaining ~21.3% of FMD variance. Isoferulic acid glucuronide and 4‑hydroxybenzaldehyde were independent predictors of DBP and SBP (exploratory analyses). Higher isovanillic acid correlated with greater platelet inhibition (ADP 10 μM) and certain hydroxybenzoic acids correlated with IL‑8.

Safety

– Three nonserious adverse events (two after blackcurrant, one after placebo) were reported; no serious adverse events occurred.

Expert commentary and mechanistic considerations

This trial contributes clinically relevant mechanistic data supporting that an anthocyanin‑rich blackcurrant beverage can acutely mitigate postprandial endothelial dysfunction, platelet hyperreactivity, and an inflammatory cytokine response provoked by a high‑fat meal in healthy adults. The translational plausibility rests on several observations:

- Anthocyanin metabolites (not parent compounds) appear rapidly in circulation and correlate with outcomes — implicating hepatic and gut microbial biotransformation as central to activity.

- Potential mechanisms include enhancement of nitric oxide (NO) bioavailability, antioxidant modulation of NADPH oxidase activity, direct effects on platelet signalling pathways, and anti‑inflammatory modulation (reduced neutrophil chemoattractant IL‑8).

- The magnitude of FMD improvement (if sustained with habitual intake) may have clinical relevance: small absolute improvements in FMD are associated with reduced cardiovascular events in observational studies; however, acute effects do not equate to long‑term benefit without supporting chronic data.

Limitations to keep in mind:

- The study assesses acute responses in a healthy, relatively low‑risk cohort. Reductions in endothelial dysfunction and platelet reactivity postprandially are promising, but extrapolation to long‑term CVD prevention, or to people with established cardiometabolic disease, is premature.

- Secondary endpoints and metabolite association analyses were exploratory and not corrected for multiple testing, increasing the risk of type I error.

- Female participants were not synchronized to a single menstrual phase; sex hormones can affect vascular measures such as FMD.

- The intervention dose (711 mg anthocyanins) is high relative to many dietary servings; feasibility and dose–response remain to be clarified.

Conclusion and clinical implications

This well‑conducted acute crossover RCT (Amini et al., NCT02459756) shows that a single dose of an anthocyanin‑rich blackcurrant drink ameliorates the deleterious vascular, platelet, and inflammatory responses triggered by a high‑fat meal in healthy adults. Effects were associated with specific circulating phenolic metabolites, suggesting biotransformation is critical to clinical action. While the findings support the concept that anthocyanin‑rich foods can modulate transient postprandial cardiovascular perturbations, the evidence is not yet sufficient to recommend high‑dose supplements for CVD prevention.

Practical takeaways for clinicians:

- Encourage regular consumption of anthocyanin‑rich berries (e.g., blackcurrants, blueberries, bilberries) as part of a balanced diet — this trial adds mechanistic support for vascular and antiplatelet benefits in the postprandial setting.

- Do not substitute dietary counselling with anthocyanin supplements until replicated longer‑term trials demonstrate clinical benefit and safety.

- Consider that gut microbiome composition and habitual diet may influence the generation of bioactive metabolites and thus individual responses.

Research priorities

Future work should include randomized controlled trials of longer duration and clinically relevant populations (hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes), dose–response studies, and mechanistic investigations into microbial contributions to metabolite formation. Testing isolated metabolites identified here (e.g., isovanillic acid derivatives) could validate causal pathways. Studies should be powered for clinical surrogate endpoints and include standardized assessment of female hormonal status.

Selected references

1) Amini AM et al. Acute effects of an anthocyanin‑rich blackcurrant beverage on markers of cardiovascular disease risk in healthy adults: randomized, double‑blind, placebo‑controlled, crossover trial. (current trial; NCT02459756).

2) Cassidy A, et al. High anthocyanin intake is associated with a reduced risk of myocardial infarction in young and middle‑aged women. Circulation. 2013;127(2):188–196.

3) Rodriguez‑Mateos A, et al. Intake and time dependence of blueberry‑flavonoid induced improvements in vascular function: randomized, controlled, double‑blind, crossover intervention with mechanistic insights. Am J Clin Nutr. 2013;98(5):1179–1191.

4) Czank C, et al. Human metabolism and elimination of the anthocyanin cyanidin‑3‑glucoside: a 13C‑tracer study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2013;97(5):995–1003.

5) Inaba Y, Chen JA, Bergmann SR. Prediction of future cardiovascular outcomes by FMD of brachial artery: a meta‑analysis. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2010;26(6):631–640.

For clinicians seeking practical guidance: recommend a varied diet rich in berries and whole plant foods; recognize that high‑dose anthocyanin interventions show promise but require confirmation in longer, outcome‑driven trials.