Introduction: The Evolving Landscape of Percutaneous Coronary Intervention in Diabetes

The management of coronary artery disease (CAD) in patients with diabetes mellitus remains one of the most formidable challenges in interventional cardiology. Historically, patients with diabetes have faced significantly worse outcomes following percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) compared to their non-diabetic counterparts. These outcomes include higher rates of myocardial infarction, target lesion revascularization, and the most feared complications of the procedure: stent failure.

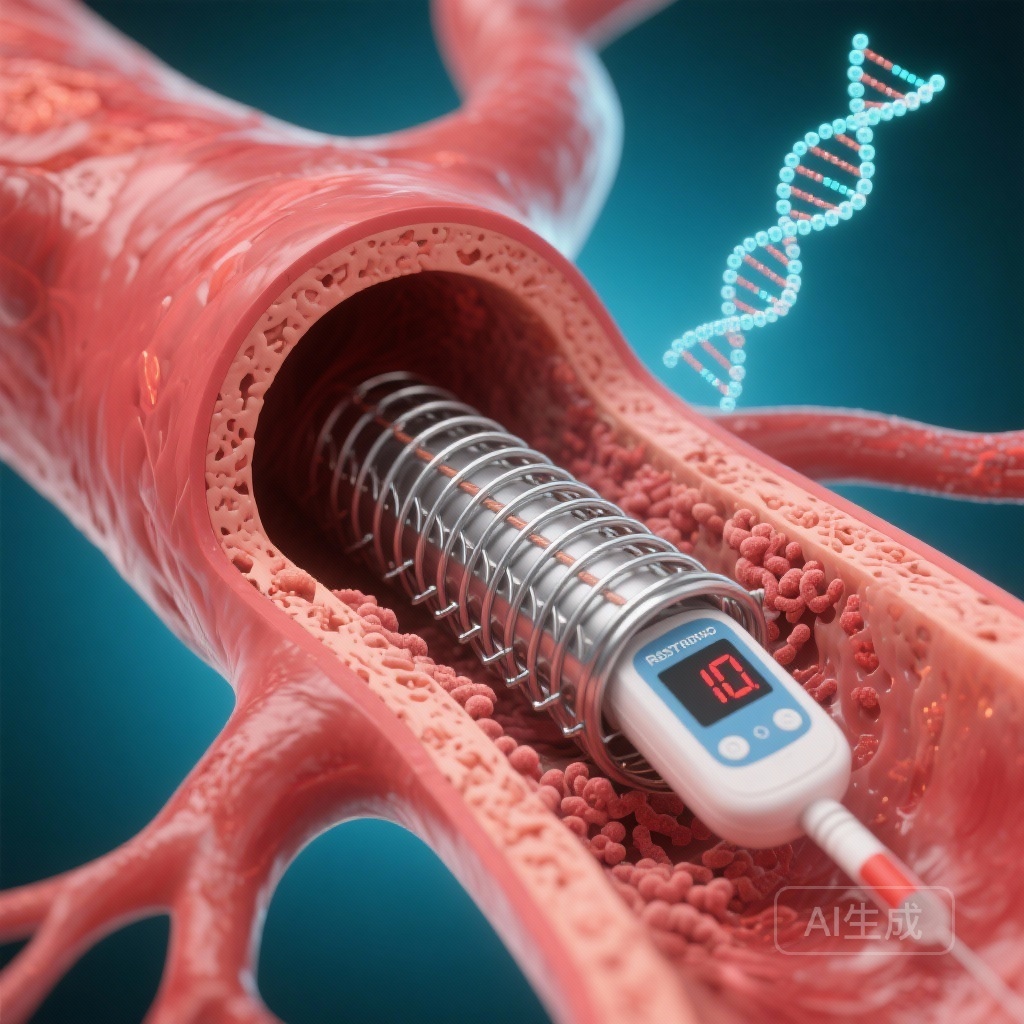

Stent failure, manifested as either in-stent restenosis (ISR) or stent thrombosis (ST), represents a clinical failure of the local mechanical and pharmacological intervention. While the advent of second-generation drug-eluting stents (DES)—featuring thinner struts, more biocompatible polymers, and more effective limus-based antiproliferative drugs—has dramatically reduced these risks for the general population, the extent to which they have mitigated the ‘diabetes tax’ remains a subject of intense investigation. Until recently, large-scale data specifically comparing the long-term failure rates of second-generation DES between Type 1 and Type 2 diabetes versus non-diabetic populations have been limited. This analysis of the SWEDEHEART registry provides much-needed clarity on the clinical burden of stent failure in this high-risk population.

Study Design and Methodology: A Decade of Real-World Evidence

The study utilized the Swedish Web-system for Enhancement and Development of Evidence-based care in Heart disease Evaluated According to Recommended Therapies (SWEDEHEART) registry, a nationwide platform known for its high data quality and near-total coverage of PCI procedures in Sweden. The researchers included all patients who received second-generation DES between 2010 and 2020.

The cohort was categorized into three distinct groups: patients with Type 1 diabetes (T1D), patients with Type 2 diabetes (T2D), and a reference group of individuals without diabetes. The primary endpoint was defined as stent failure, a composite of clinically significant in-stent restenosis or definite stent thrombosis.

To ensure the validity of the findings, the researchers employed Cox regression models to estimate adjusted hazard ratios (HRs), accounting for a wide array of baseline characteristics including age, sex, smoking status, indication for PCI (stable CAD vs. acute coronary syndrome), and procedural variables such as the number of stents and total stent length. Furthermore, sensitivity analyses were performed to address the competing risk of death—a crucial step in a population where diabetic patients often have higher non-cardiac mortality.

Key Findings: The Stratified Risk of Diabetes

The study included a massive cohort of 160,523 patients, reflecting a decade of clinical practice. Of these, 2,406 were identified as having T1D, 43,377 had T2D, and 114,740 were non-diabetic. The patient demographic was predominantly male (71%), with a mean follow-up period of 4.5 years, providing sufficient time to observe late-stage stent failures.

During the follow-up, 5,510 stent failure events were recorded. The data revealed a clear and significant hierarchy of risk:

Type 1 Diabetes: The Highest Vulnerability

Patients with T1D faced the most substantial risk. The fully adjusted hazard ratio for stent failure was 2.28 (95% CI 1.97-2.65) compared to patients without diabetes. This indicates that T1D patients are more than twice as likely to experience stent failure even when using modern, second-generation DES technology.

Type 2 Diabetes: A Persistent Increase in Risk

Patients with T2D also exhibited a significantly elevated risk, though lower than the T1D group. The adjusted HR was 1.35 (95% CI 1.27-1.44) relative to the reference group. While 35% may seem modest compared to the T1D group, the sheer volume of T2D patients in clinical practice makes this a major public health concern.

Components of Stent Failure

Importantly, the increased risk in diabetic patients was not limited to one type of failure. Both in-stent restenosis (the gradual narrowing of the stent due to tissue growth) and stent thrombosis (the sudden formation of a blood clot within the stent) were significantly more frequent in both diabetic cohorts. This suggests that diabetes affects both the biological healing process (endothelialization) and the thrombogenicity of the blood-stent interface.

Mechanistic Insights: Why Does Diabetes Compromise Stents?

The findings from SWEDEHEART underscore the aggressive nature of diabetic vasculopathy. Several biological mechanisms likely contribute to the observed results. In patients with diabetes, chronic hyperglycemia and insulin resistance lead to a state of systemic inflammation and increased oxidative stress. This environment impairs the function of endothelial progenitor cells, which are essential for the proper re-endothelialization of the stented segment.

In T1D, the risk is likely exacerbated by the early onset and longer duration of the disease, leading to more extensive and diffuse coronary calcification and smaller vessel diameters—factors that are known predictors of stent failure. Additionally, patients with diabetes often exhibit ‘sticky’ platelets and an impaired fibrinolytic system, increasing the likelihood of stent thrombosis even on standard dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT).

Furthermore, the phenomenon of neoatherosclerosis—the development of new atherosclerotic plaques inside the stented segment—occurs more rapidly and frequently in diabetic patients. These new plaques are often unstable and can lead to late stent failure years after the initial procedure.

Clinical Implications and Expert Commentary

These results have profound implications for how clinicians approach coronary revascularization in patients with diabetes. First, the stark difference in risk between T1D and T2D suggests that T1D should be viewed as an ultra-high-risk category in the catheterization lab. Clinicians might need to consider more aggressive procedural strategies, such as the routine use of intravascular imaging (IVUS or OCT) to ensure optimal stent expansion and apposition, which are critical for preventing failure.

Second, the findings reinforce the importance of intensive secondary prevention. Given the high rates of stent failure, optimizing glycemic control, blood pressure, and lipid levels is non-negotiable. The use of modern glucose-lowering therapies with proven cardiovascular benefits, such as SGLT2 inhibitors and GLP-1 receptor agonists, may play a role in improving long-term vessel patency, although more specific data on their impact on stent failure are needed.

From a policy and guidelines perspective, this study supports a potential preference for coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) over PCI in diabetic patients with multivessel disease, as currently recommended by most international guidelines (e.g., ESC/EACTS). However, for those who must undergo PCI, the choice of stent and the duration of antithrombotic therapy must be carefully tailored to their high-risk profile.

Study Limitations

While the study is robust due to its size and real-world nature, it is observational. Some confounders, such as longitudinal HbA1c levels, duration of diabetes, and adherence to medical therapy, were not fully captured in the registry. Additionally, while the study focused on second-generation DES, the specific brand of stent used could vary, though most modern DES perform similarly.

Conclusion

The SWEDEHEART study provides definitive evidence that diabetes remains a potent risk factor for stent failure in the era of second-generation drug-eluting stents. The risk is particularly pronounced in patients with Type 1 diabetes, who face more than double the failure rate of non-diabetics. These findings demand a heightened level of clinical vigilance, meticulous procedural technique, and aggressive long-term medical management for all diabetic patients undergoing coronary stenting.

References

1. Santos-Pardo I, Andersson Franko M, Hofmann R, Nyström T. Coronary Stent Failure in Patients With Diabetes: A Nationwide Observational Study From SWEDEHEART. Diabetes Care. 2026 Feb 1;49(2):266-276. doi: 10.2337/dc25-1624. PMID: 41299809.

2. Byrne RA, et al. 2023 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes. European Heart Journal. 2023;44(38):3720-3826.

3. Neumann FJ, et al. 2018 ESC/EACTS Guidelines on myocardial revascularization. European Heart Journal. 2019;40(2):87-165.