Highlights

– In SURMOUNT‑1 participants with obesity and prediabetes, tirzepatide (5/10/15 mg weekly) produced dose‑dependent reductions in 10‑year predicted ASCVD and total CVD risk compared with placebo at week 176.

– Predicted 10‑year risk of progression to type 2 diabetes declined markedly with tirzepatide (absolute reductions vs placebo ~13–16 percentage points on CMDS).

– Risk reductions tracked with weight loss and improvements in cardiometabolic parameters; findings support potential broad cardiometabolic benefit of tirzepatide in this population, while definitive clinical outcome data are awaited.

Background: clinical context and unmet need

Obesity and prediabetes are highly prevalent conditions that substantially increase future risk of type 2 diabetes (T2D) and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD). Even modest weight loss can improve glycemic indices, blood pressure, and lipids, translating into reduced cardiometabolic risk. However, durable, pharmacologic weight‑loss interventions that meaningfully modify long‑term disease risk have been limited until recently.

Tirzepatide is a once‑weekly, dual glucose‑dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP) and glucagon‑like peptide‑1 (GLP‑1) receptor agonist that produces robust weight loss and glycemic improvements. The SURMOUNT‑1 program evaluated tirzepatide for weight management in adults with obesity without diabetes; a subset had prediabetes at baseline. The post hoc analysis by Hankosky et al. (Diabetes Obes Metab. 2025) applies validated risk engines to three‑year trial data to estimate changes in 10‑year predicted risks of CVD and T2D following tirzepatide treatment.

Study design and methods

This is a post hoc analysis of SURMOUNT‑1, a randomized, double‑blind, placebo‑controlled, phase 3 trial. Key features:

- Population: 2,539 adults with body‑mass index (BMI) ≥30 kg/m2 or ≥27 kg/m2 with one weight‑related comorbidity, excluding diabetes. Analyses focused on the subgroup with obesity and prediabetes at baseline.

- Intervention: Once‑weekly subcutaneous tirzepatide with dose escalation to 5 mg, 10 mg, or 15 mg, versus matched placebo. Duration for this analysis: 176 weeks (3 years) of treatment.

- Endpoints: Original trial coprimary endpoints were percent change in weight and achieving ≥5% weight loss. For the post hoc work, validated risk prediction tools were applied at baseline and week 176 to estimate 10‑year risk of: ASCVD, heart failure (HF), total CVD, and progression to T2D.

- Risk engines: The analysis used the ACC/AHA pooled cohort (ASCVD) equation and the PREVENT risk model for ASCVD, equations for HF and total CVD, and the Cardiometabolic Disease Staging (CMDS) instrument for 10‑year T2D risk. Changes from baseline to week 176 were compared between tirzepatide dose groups and placebo using mixed models for repeated measures, under a treatment‑regimen estimand (intention‑to‑treat irrespective of treatment discontinuation).

Key results

The principal findings are summarized below. All comparisons reported as statistically significant vs placebo (p < 0.0001) unless noted.

Predicted 10‑year ASCVD risk

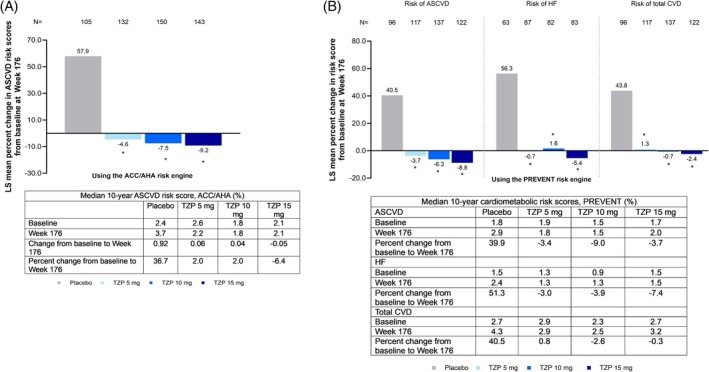

Using the ACC/AHA pooled cohort equation, mean percent change from baseline to week 176 in predicted ASCVD risk decreased in a dose‑dependent manner with tirzepatide and increased with placebo. Reported mean percent changes were:

- Tirzepatide 5 mg: −4.6%

- Tirzepatide 10 mg: −7.5%

- Tirzepatide 15 mg: −9.2%

- Placebo: +57.9%

Using the PREVENT risk equation, a similar pattern emerged (5 mg: −3.7%; 10 mg: −6.3%; 15 mg: −8.8% vs placebo +40.5%). The magnitude and direction of change consistently favored tirzepatide across ASCVD algorithms.

Fig. Effect of tirzepatide on 10‐year predicted risk of cardiovascular outcomes in participants with obesity or overweight and prediabetes. (A) Percent change in 10‐year predicted risk of ASCVD at week 176 in participants with obesity or overweight and prediabetes, using the ACC/AHA risk engine; median ASCVD risk scores at baseline, week 176, change, and percent change at week 176 are presented in the table below the plot. (B) Percent change in 10‐year predicted risk of ASCVD, HF, total CVD at week 176 in participants with obesity or overweight and prediabetes, using the PREVENT risk engine; median risk scores at baseline, week 176, and percent change at week 176 from baseline are presented in the table below the plot. All comparisons of risk reductions from baseline between tirzepatide dose groups and placebo were significant at *p < 0.0001 vs. placebo. The percent change in predicted risk from baseline to week 176 was derived from an MMRM analysis using the SURMOUNT‐1 (3‐year trial) efficacy analysis set. It included data obtained during the treatment period from the mITT (all randomized participants who received at least 1 dose of the study drug), excluding data after discontinuation of the study drug (last dose date +7 days). Source: Only participants with at least one non‐missing post‐baseline value of the response variable were included in the analysis. Change in predicted risk for ASCVD and HF using the PREVENT risk engine was planned as a sensitivity analysis. ASCVD, atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease; BMI, body mass index; CVD, cardiovascular disease; N, number of subjects in the population with baseline and post‐baseline value at the specified time point; MMRM, mixed model for repeated measures; mITT, modified intent to treat; TZP, tirzepatide.

Predicted 10‑year heart failure and total CVD risk

Tirzepatide treatment was associated with greater reductions in predicted HF and total CVD risk compared with placebo. Absolute and relative declines paralleled the dose–response pattern observed for ASCVD risk, consistent with improvements in blood pressure, weight, and metabolic parameters that influence HF risk.

Predicted 10‑year risk of progression to type 2 diabetes (CMDS)

Using the Cardiometabolic Disease Staging tool, mean absolute changes in predicted T2D risk from baseline to week 176 were markedly larger with tirzepatide versus placebo:

- Tirzepatide 5 mg: −17.0%

- Tirzepatide 10 mg: −19.6%

- Tirzepatide 15 mg: −19.5%

- Placebo: −4.3%

These reductions reflect substantial lowering of the modeled 10‑year probability of T2D in the tirzepatide groups compared to minimal change with placebo.

Drivers of risk change

Risk improvements tracked with weight loss and favorable changes in systolic blood pressure, fasting glucose, and lipid variables reported in the trial. The dose‑response behavior of risk reduction mirrors the dose‑dependent weight loss achieved with tirzepatide in SURMOUNT‑1.

Safety and tolerability (trial context)

While this post hoc analysis focuses on modeled risk, safety outcomes in the parent SURMOUNT‑1 population were consistent with the known profile of incretin‑based therapies: dose‑related gastrointestinal adverse events were the most common, with few discontinuations for safety. This analysis did not report new safety signals specific to the cardiometabolic risk models.

Interpretation and clinical perspective

The post hoc analysis suggests that tirzepatide yields clinically meaningful reductions in modeled 10‑year risks for both cardiovascular disease and progression to T2D in adults with obesity and prediabetes. Several points merit emphasis:

- Magnitude and consistency: Results were consistent across different cardiovascular risk calculators (ACC/AHA and PREVENT) and showed clear dose dependence, supporting internal validity of the finding.

- Mechanistic plausibility: Tirzepatide combines robust weight loss with improvements in glycemia, blood pressure, and lipids—key upstream determinants of both ASCVD and HF risk as well as diabetes progression.

- Modeled vs observed outcomes: These are predictions from validated risk engines, not measured clinical events. Risk engines translate short‑term changes in risk markers into estimated future event likelihood; they provide useful insight into potential benefit but cannot substitute for randomized controlled cardiovascular outcome trials.

- Implication for prevention: If confirmed in long‑term outcome studies, tirzepatide could represent a pharmacologic strategy to prevent or delay T2D and reduce cardiovascular risk in high‑risk people with obesity and prediabetes.

Limitations

Key limitations of the analysis include:

- Post hoc nature: The analysis was not prespecified as a primary endpoint of SURMOUNT‑1 and is therefore exploratory.

- Risk prediction vs hard outcomes: Risk engines, while validated, have intrinsic uncertainty and may misestimate absolute risk in populations treated with agents that produce large changes in risk factors. Calibration of equations may not fully account for effects of novel pharmacotherapies.

- Generalizability: Trial participants were a selected clinical trial cohort without diabetes at baseline; external validity to broader populations (different age ranges, racial/ethnic groups, comorbidity profiles) requires caution.

- Residual confounding: Although randomized for treatment, analyses of modeled risk may be influenced by missing data, differential adherence, or postrandomization changes not fully captured by models.

How this fits with existing evidence

Large‑magnitude weight loss with tirzepatide is already documented in the SURMOUNT program, and the agent improves glycemic markers in people with and without diabetes. Existing GLP‑1 receptor agonist trials (liraglutide, semaglutide) have demonstrated cardiovascular outcome benefits in people with type 2 diabetes and elevated cardiovascular risk; whether dual GIP/GLP‑1 receptor agonism provides similar or greater cardiovascular protection independent of glycemic status remains under study. Ongoing dedicated cardiovascular outcome trials will be required to determine whether the modeled risk reductions translate into fewer clinical events.

Clinical implications and next steps

For clinicians managing patients with obesity and prediabetes, these modeled results offer encouraging evidence that pharmacologic therapy with tirzepatide could meaningfully alter long‑term cardiometabolic risk profiles when sustained. Practical implications include:

- Consideration of tirzepatide for eligible patients seeking clinically significant and durable weight loss with the additional potential to reduce progression to diabetes and lower predicted cardiovascular risk.

- Need to individualize therapy by balancing efficacy with tolerability, contraindications, cost, and patient preferences; monitor for gastrointestinal adverse events and counsel on expectations and adherence.

- Tempest caution: Until results from dedicated cardiovascular outcome trials are available, clinicians should treat modeled risk reductions as hypothesis‑generating rather than definitive evidence of reduced event rates.

Conclusion

The SURMOUNT‑1 post hoc analysis indicates that tirzepatide produces dose‑dependent reductions in 10‑year predicted risk of ASCVD, heart failure, total CVD and progression to type 2 diabetes among adults with obesity and prediabetes. These modeled benefits are biologically plausible and driven by robust weight loss and improvements in cardiometabolic risk factors. Confirmation in prospective cardiovascular outcome trials and real‑world studies will be essential to determine whether the predicted benefits translate into fewer clinical events and improved long‑term outcomes.

Funding and clinicaltrials.gov

The analysis and parent trial were funded and conducted as reported in the primary publication. For trial registration details and primary SURMOUNT‑1 protocol information, refer to the original SURMOUNT‑1 publications and clinicaltrials.gov entry as cited below.

References

Hankosky ER, Lebrec J, Lee CJ, Dimitriadis GK, Jouravskaya I, Stefanski A, Garvey WT. Tirzepatide and the 10‑year predicted risk of cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes in adults with obesity and prediabetes: A post hoc analysis from the three‑year SURMOUNT‑1 trial. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2025 Dec;27(12):7385‑7394. doi:10.1111/dom.70143 IF: 5.7 Q1 . PMID: 41017451 IF: 5.7 Q1 ; PMCID: PMC12587230 IF: 5.7 Q1 .

Knowler WC, Barrett‑Connor E, Fowler SE, et al. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(6):393‑403.

Goff DC Jr, Lloyd‑Jones DM, Bennett G, et al. 2014 Guideline on the Assessment of Cardiovascular Risk: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2014;129(25 Suppl 2):S49‑S73. (Pooled Cohort Equations)

Marso SP, Daniels GH, Brown‑Frandsen K, et al. Liraglutide and Cardiovascular Outcomes in Type 2 Diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:311‑322.

AI thumbnail prompt

Generate a clean, modern infographic style image: a middle‑aged adult with obesity in profile silhouette standing beside a vertical 10‑year timeline. Place heart and pancreas icons at different timeline points. Show downward red arrows and green check marks indicating reduced risk. Use muted clinical colors (blues, greens), include faint medical graphs and an injection pen on a table to suggest therapy. High resolution, professional, editorial look.