Highlights

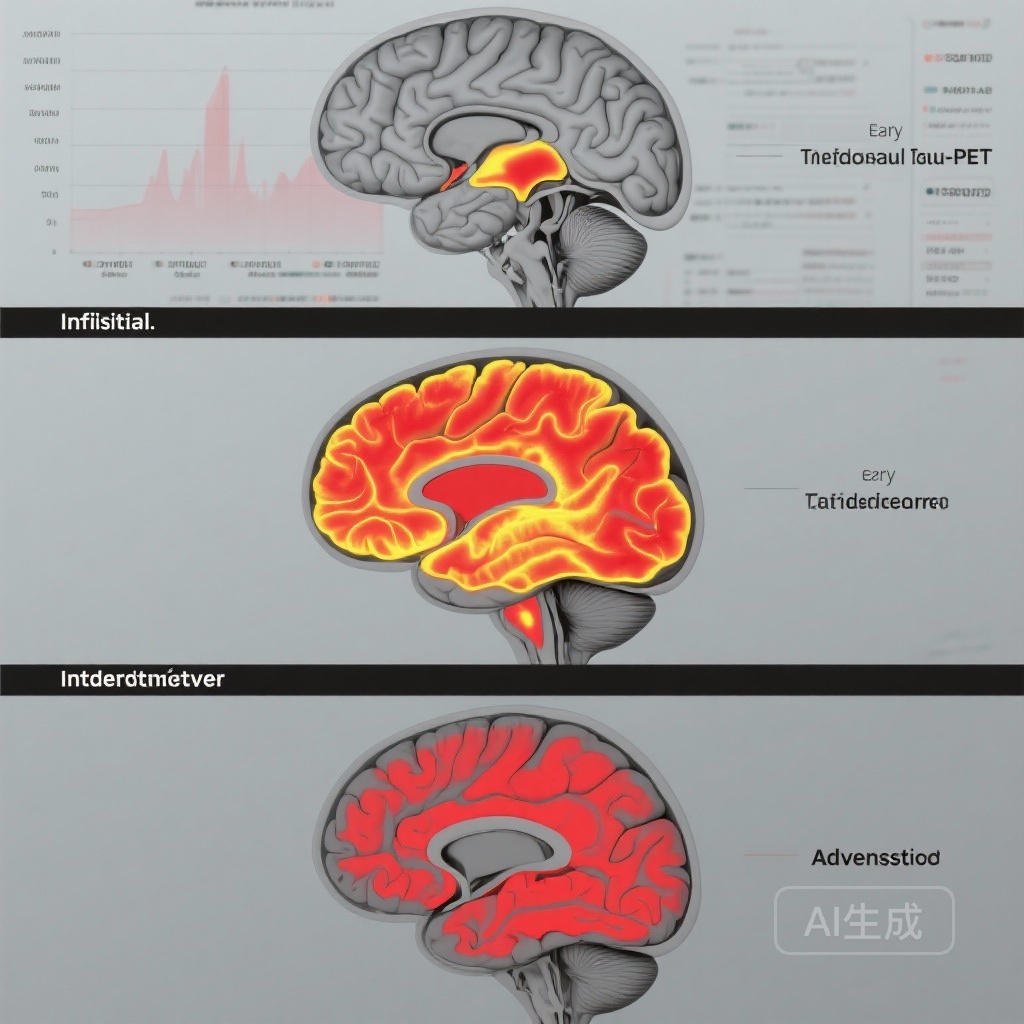

– Longitudinal tau-PET accumulation is stage-dependent: minimal change in A+T2- (initial), localized increases in early stage, and progressively broader accumulation in intermediate and advanced stages.

– Baseline biological AD staging (A+/T staging) predicted both the regional distribution and magnitude of subsequent tau spread across two independent cohorts (TRIAD and ADNI).

– Choosing outcome regions of interest (ROIs) matched to disease stage reduced estimated trial sample sizes by 30%–93% for hypothetical disease-modifying effects.

Background

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is increasingly conceptualized as a biological continuum defined by in vivo biomarkers of amyloid-β (A) and tau (T) pathology and neurodegeneration (N) rather than by clinical symptoms alone. The NIA-AA research framework formalized this approach, enabling trials to recruit and stratify participants by biomarker-defined disease stage and to select biomarker outcomes that reflect target biology and stage-specific pathology (Jack et al., 2018). Tau positron emission tomography (tau-PET) is now widely used both to stage disease biologically and as a candidate pharmacodynamic outcome for anti-tau or anti-amyloid interventions. Yet, longitudinal patterns of tau-PET accumulation across biological AD stages — and how these patterns should guide ROI selection and sample-size planning for trials — have not been fully quantified in large, well-characterized cohorts.

Study design

Trudel and colleagues performed a retrospective longitudinal analysis of participants drawn from two observational cohorts: the Translational Biomarkers in Aging and Dementia (TRIAD) study and the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI). Participants underwent baseline amyloid-PET and tau-PET imaging and were followed longitudinally for a mean of approximately 3 years (±1.35 years). Biological AD staging was applied to amyloid-positive individuals using a tau-PET–based taxonomy: A+T2- (initial), A+T2MTL+ (early; medial temporal lobe tau), A+T2MOD+ (intermediate; more widespread temporoparietal involvement), and A+T2HIGH+ (advanced; extensive neocortical tau). Amyloid-PET–negative participants served as non-AD controls. The primary analysis used linear mixed-effects models to estimate longitudinal regional tau-PET change by stage. Secondary analyses included statistical power and sample-size simulations to estimate the number of participants required to detect hypothetical disease-modifying effects on tau accumulation when ROIs were aligned versus non-aligned with baseline stage.

Key findings

Population: The pooled analysis included 542 participants (mean age 67.9 ± 15.3 years, 56.3% female), with 321 non-AD controls and 221 biomarker-defined AD cases.

Stage determines both distribution and rate of tau accumulation

The principal finding is that baseline tau stage predicted both where and how rapidly tau-PET signal increased over time. Specifically:

- No meaningful longitudinal tau accumulation was observed over 4–6 years in A+T2- (initial) individuals, indicating a prolonged latency before measurable PET-detectable tau spread outside subthreshold levels in amyloid-positive but tau-negative persons.

- Early-stage (A+T2MTL+) participants demonstrated localized tau accumulation restricted to early-affected regions (TRIAD: β = 0.15, 95% CI 0.09–0.21, p < 0.001; ADNI: β = 0.21, 95% CI 0.03–0.40, p = 0.03), consistent with progressive involvement of limbic and medial temporal structures.

- Intermediate-stage (A+T2MOD+) participants showed accumulation in intermediate-distribution regions (TRIAD: β = 0.16, 95% CI 0.10–0.22, p < 0.001; ADNI: β = 0.37, 95% CI 0.15–0.59, p = 0.001), indicating temporoparietal spread beyond medial temporal lobes.

- Advanced-stage (A+T2HIGH+) participants exhibited the largest and most widespread increases in later-affected neocortical regions (TRIAD: β = 0.45, 95% CI 0.39–0.50, p < 0.001; ADNI: β = 0.31, 95% CI 0.14–0.49, p < 0.001).

Implications for ROI selection and trial efficiency

Statistical power simulations showed that selecting tau-PET ROIs that are stage-appropriate (i.e., focusing on regions expected to accumulate tau given baseline stage) markedly reduced estimated sample sizes required to detect a hypothetical disease-modifying effect on tau progression. Reported reductions ranged from 30% to 93% depending on stage and cohort. The largest gains occurred when advanced-stage ROIs were used in populations already demonstrating extensive baseline tau — a setting where both baseline signal and dynamic range are greatest.

Reproducibility across cohorts

Findings were consistent across the independent TRIAD and ADNI cohorts despite differences in tracer, acquisition protocols, and participant demographics, supporting the generalizability of stage-dependent tau dynamics. The authors note, however, that tracer heterogeneity and cohort composition remain key limitations to cross-study harmonization.

Expert commentary

These results validate a pragmatic principle for AD trials: align participant selection and outcome measurement with the prevailing biology. For tau-targeting therapeutics, enrolling participants with the appropriate tau stage is critical. In early or pre-tau stages (A+T2-), trials that rely on tau-PET change as a primary outcome may be underpowered because little to no PET-detectable change occurs over several years. In contrast, participants with intermediate or advanced tau stages offer measurable longitudinal change and greater statistical signal, but they may be less amenable to disease-modifying interventions if downstream neurodegeneration is already established.

From a mechanistic perspective, the stage-dependent propagation of tau observed here echoes neuropathological Braak staging, where tau pathology begins in transentorhinal/entorhinal cortices before spreading to limbic and neocortical regions (Braak & Braak, 1991). The PET-based staging operationalizes this neuropathological cascade in vivo, enabling targeted trial designs.

Limitations to consider: the study is retrospective and observational, so causal inferences about therapeutic modulation cannot be made. Differences in PET tracers, image processing, demographic composition, and follow-up duration across cohorts may introduce heterogeneity in effect estimates. Finally, tau-PET quantification has technical caveats (off-target binding for some ligands, partial-volume effects) that can influence sensitivity to change.

Clinical and trial-design implications

For sponsors and investigators planning disease-modifying trials, practical takeaways include:

- Use biomarker staging (A/T framework) at screening to ensure that enrolled participants have the tau burden and expected dynamic range appropriate for the chosen outcome. Avoid relying on tau-PET as a longitudinal outcome in A+T2- populations unless expected effect sizes are large or follow-up is very long.

- Select ROI(s) aligned with baseline stage (e.g., medial temporal ROIs for early-stage participants, temporoparietal or global neocortical ROIs for intermediate/advanced stages) to maximize power and reduce sample sizes and costs.

- Consider combining biomarker outcomes (tau-PET plus fluid markers or structural MRI) when targeting earlier stages to capture complementary signals that may change before PET-detectable tau accumulates.

- Pre-specify harmonized imaging protocols and tracer use across sites where possible to reduce measurement heterogeneity; when multiple tracers are necessary, apply validated cross-tracer standardization methods.

Conclusion

Trudel et al. provide robust longitudinal evidence that tau-PET accumulation is strongly stage-dependent in biologically defined AD. Baseline A/T-based staging forecasts both regional patterns and rates of subsequent tau spread, and aligning outcome ROIs with disease stage can materially improve trial efficiency. These findings argue for routine application of biological staging during trial screening and for careful, stage-matched selection of imaging endpoints in AD therapeutic development.

Funding and clinicaltrials.gov

Primary funding and cohort-specific support details are reported in the original article (Trudel et al., Neurology 2025). ADNI is a public-private partnership supported by multiple NIH grants and industry contributors; TRIAD receives institutional and grant support as described in cohort documentation. No clinicaltrials.gov identifiers apply to this retrospective observational analysis.

References

Trudel L, Therriault J, Macedo AC, Servaes S, Hosseini SA, Bezgin G, Aumont E, Rahmouni N, Fernandez Arias J, Zheng Y, Wang YT, Chan T, Hall BJ, Hopewell R, Hsiao CH, Ferreira PCL, Bellaver B, Vitali P, Soucy JP, Pascoal TA, Gauthier S, Rosa-Neto P; Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. Implication for Clinical Trials From Longitudinal Tau-PET Accumulation Across Biological Alzheimer Disease Stages. Neurology. 2025 Oct 21;105(8):e214111. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000214111. PMID: 40986433; PMCID: PMC12459282.

Jack CR Jr, Bennett DA, Blennow K, Carrillo MC, Dunn B, Haeberlein SB, Holtzman DM, Jagust W, Jessen F, Karlawish J, et al. NIA-AA Research Framework: Toward a biological definition of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2018 Apr;14(4):535-562. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2018.02.018.

Braak H, Braak E. Neuropathological stageing of Alzheimer-related changes. Acta Neuropathol. 1991;82(4):239–259. doi:10.1007/BF00308809.