Highlights

– In FINEARTS‑HF (n=6001; EF ≥40%), 1013 deaths occurred (16.9%) over median 32 months; 49.6% were adjudicated cardiovascular and 42.8% of cardiovascular deaths were sudden.

– Patients with baseline EF <50% had higher proportions of overall and cardiovascular mortality driven principally by excess sudden death; heart‑failure death rates were similar across EF strata.

– Randomization to finerenone did not significantly affect all‑cause or cause‑specific mortality across EF categories; the analysis was likely underpowered for mortality endpoints.

Background and disease burden

Heart failure with preserved (HFpEF) or mildly reduced ejection fraction (HFmrEF) represents a growing proportion of the heart‑failure population, particularly among older adults with multimorbidity. These syndromes are heterogeneous in pathophysiology and prognosis, and unlike heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF), evidence for therapies that reduce mortality has been limited until recently. Understanding how mode of death varies across the EF spectrum is clinically important for risk stratification, tailoring therapies (including consideration of devices), and designing future trials targeting specific fatal events such as sudden death.

Study design

Overview

This report is a prespecified secondary analysis of the FINEARTS‑HF randomized clinical trial (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT04435626). FINEARTS‑HF enrolled 6001 patients with symptomatic heart failure and left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) ≥40% who were randomized to the oral nonsteroidal mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist finerenone versus placebo. Median follow‑up for the trial was 32 months (IQR 23–36).

Objectives and endpoints

The prespecified analysis evaluated centrally adjudicated mode of death across baseline EF categories (<50%, ≥50–<60%, and ≥60%) and investigated whether randomized treatment with finerenone modified cause‑specific mortality using Cox proportional hazards models.

Key findings

Overall mortality and adjudicated modes

Among the 6001 trial participants, 1013 (16.9%) died during follow‑up (median age of decedents 76 years, IQR 69–82; 58.6% male). The clinical end points committee adjudicated causes as cardiovascular in 502 patients (49.6%), noncardiovascular in 368 (36.3%), and undetermined in 143 (14.1%).

Of the 502 cardiovascular deaths:

– Sudden death: 215 (42.8%)

– Heart‑failure death: 163 (32.4%)

– Stroke: 48 (9.6%)

– Myocardial infarction: 25 (5.0%)

– Other cardiovascular causes: 51 (10.2%)

These distributions show that sudden death constituted the single largest category of cardiovascular mortality in this population with EF ≥40%.

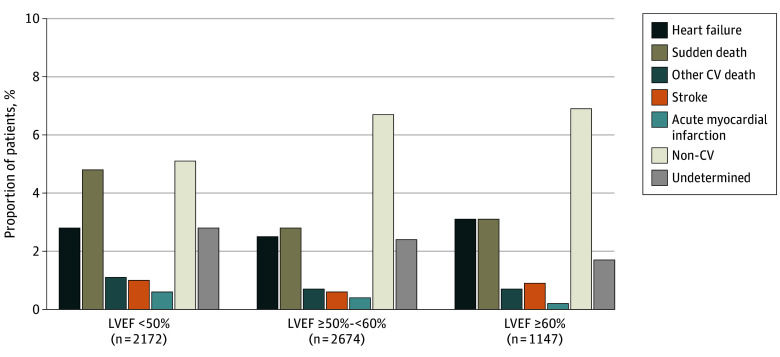

Variation by EF category

The analysis demonstrated that the proportions of all‑cause mortality, cardiovascular mortality, and sudden death were higher in participants whose baseline EF was <50% compared with those with EF ≥50%. In contrast, the proportion of deaths attributed to progressive heart failure was relatively constant across EF strata. Deaths due to myocardial infarction, stroke, and other specific cardiovascular causes were uncommon regardless of EF category.

In practical terms, patients with EF <50% within the HFmrEF/HFpEF spectrum accounted for a disproportionate burden of sudden cardiac death, suggesting a transition toward a mortality pattern reminiscent of HFrEF as EF declines.

Figure 1. Adjudicated Mode of Death According to Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction (LVEF).

CV indicates cardiovascular; p-y, patient-year.

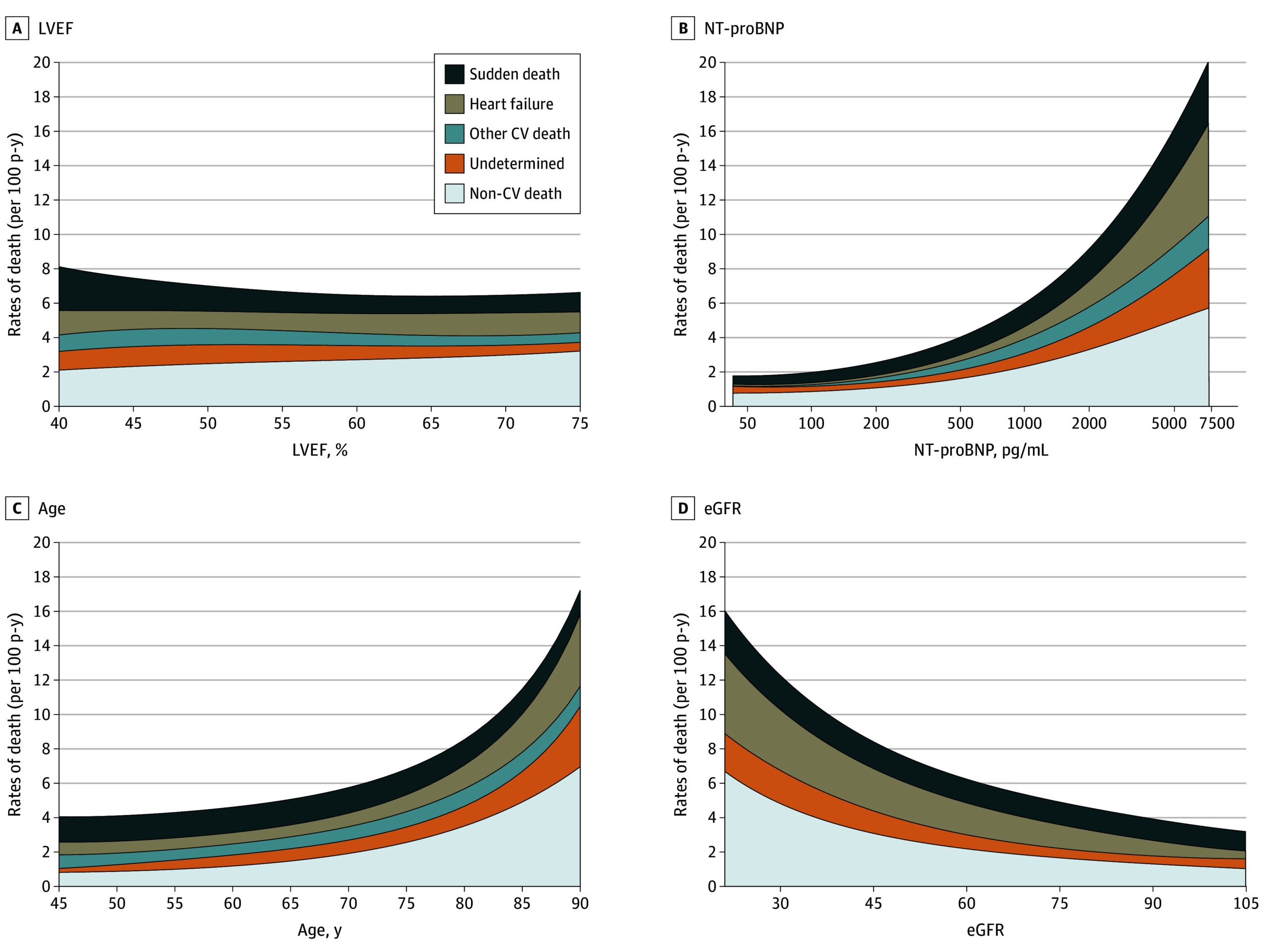

Figure 2. Variation in Incidence of Adjudicated Mode of Death by Continuous Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction (LVEF), N-Terminal Pro–Brain Natriuretic Peptide (NT-proBNP), Age, and Estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate (eGFR).

SI conversion factor: To convert NT-proBNP to nanograms per liter, multiply by 1. CV indicates cardiovascular.

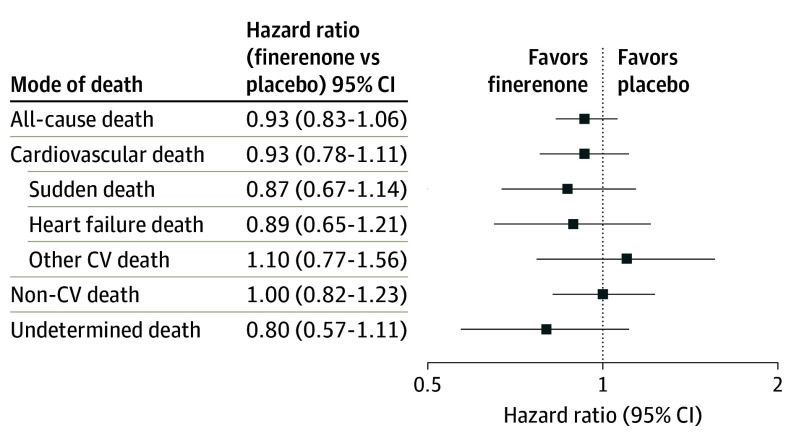

The effects of assignment to finerenone compared with placebo on cause-specific mortality are displayed in Figure 3. Although rates of overall death and cardiovascular death were numerically lower in patients allocated to finerenone, treatment with finerenone did not significantly reduce all-cause death or any specific mode of death relative to placebo. There was no detectable variation in the effects of finerenone treatment on cardiovascular mortality by LVEF or in those with HFimpEF (interaction P = .40 and 0.52, respectively).

Figure 3. Effect of Finerenone Compared With Placebo on Cause-Specific Mortality.

CV indicates cardiovascular.

Effect of finerenone on mortality

Randomization to finerenone did not significantly reduce all‑cause mortality or any cause‑specific mortality endpoint compared with placebo in any EF category in this analysis. The authors note the trial (and this prespecified secondary analysis) was likely underpowered to detect modest treatment effects on mortality, particularly cause‑specific death.

Expert commentary and interpretation

Clinical implications

These findings refine our understanding of risk across the EF spectrum in patients with symptomatic heart failure and EF ≥40%. The predominance of sudden death—especially among those with EF <50%—has several implications:

– Risk stratification: EF remains a useful marker for phenotype and risk. Patients with HFmrEF (EF 40–49% in many frameworks) may carry heightened arrhythmic risk relative to those with higher EF and may warrant closer monitoring for arrhythmia and ischemia.

– Prevention strategies: Sudden death prevention in HFrEF relies in part on guideline‑directed medical therapy (GDMT) and implantable cardioverter‑defibrillators (ICDs) when EF is reduced below threshold values. There are no randomized data supporting routine ICD implantation in HFmrEF or HFpEF, and the clinical benefit of devices in EF ≥40% remains unproven. These data, however, support renewed attention to identifying high‑risk subgroups (biomarkers, imaging, arrhythmic burden) within the HFmrEF population for targeted interventions.

– Therapeutic development and trials: Trials designed to reduce mortality in HFpEF/HFmrEF should consider mode‑specific endpoints and stratification by EF. If sudden death is a dominant mode in lower EF strata, interventions with antiarrhythmic or anti‑remodeling effects may be prioritized.

How this compares with prior trials

Previous trials in HFpEF/HFmrEF have produced mixed effects on mortality. For example, PARAGON‑HF (sacubitril/valsartan) and EMPEROR‑Preserved (empagliflozin) reduced heart‑failure hospitalizations with heterogeneous effects on mortality, and benefits have often concentrated in lower EF ranges within these trials’ populations. Historical trials such as TOPCAT (spironolactone) did not demonstrate consistent mortality reductions across broad HFpEF populations. The FINEARTS‑HF mortality analysis aligns with the pattern that lower EF within the non‑reduced EF spectrum conveys higher cardiovascular risk and may drive heterogeneity in treatment responses.

Mechanistic considerations

Sudden death in HFpEF/HFmrEF may arise from a combination of factors: underlying ischemic heart disease, electrical remodeling, myocardial fibrosis, autonomic dysfunction, and comorbidities (e.g., chronic lung disease, diabetes, renal disease). The relative contribution of arrhythmic versus nonarrhythmic sudden death is often difficult to adjudicate post‑mortem or with limited data, which complicates planning of targeted preventive measures.

Limitations

– Secondary analysis: Despite prespecification, these are secondary analyses of a randomized trial primarily powered for composite cardiovascular outcomes rather than cause‑specific mortality. Null findings for treatment effects on mortality should be interpreted cautiously.

– Event counts and power: Cause‑specific death counts (especially for myocardial infarction and stroke) were low, limiting precision of effect estimates and subgroup inferences.

– Adjudication challenges: Cause‑of‑death adjudication depends on available clinical information and may misclassify sudden vs non‑sudden events, particularly outside the hospital setting.

– Generalizability: Trial enrollment criteria and background therapies may differ from routine practice; participant characteristics (age, comorbidities) may affect extrapolation to other populations.

Conclusions and clinical takeaways

The FINEARTS‑HF adjudicated mortality analysis shows that in patients with symptomatic heart failure and EF ≥40%, cardiovascular deaths account for roughly half of fatalities and are principally driven by sudden death, especially when baseline EF is <50%. Heart‑failure deaths were distributed more evenly across EF strata. Finerenone did not demonstrably reduce cause‑specific mortality in this analysis, but the trial was not optimized to detect modest mortality effects.

Clinicians should recognize that individuals with HFmrEF (or EF toward the lower end of the ≥40% spectrum) may have increased arrhythmic risk and consider individualized evaluation for ischemia, arrhythmia monitoring, and optimization of therapies that reduce overall cardiovascular risk. Research priorities include: refining risk models to identify those at highest risk of sudden death in HFmrEF/HFpEF, investigating targeted antiarrhythmic or device strategies in well‑defined high‑risk subgroups, and conducting adequately powered trials with mode‑specific mortality endpoints.

Funding and clinicaltrials.gov

The FINEARTS‑HF trial was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT04435626). Funding and disclosures related to the original trial are reported in the primary publication (Desai et al., JAMA Cardiology 2025).

References

1. Desai AS, Jhund PS, Vaduganathan M, et al. Mode of Death in Patients With Heart Failure With Mildly Reduced or Preserved Ejection Fraction: The FINEARTS‑HF Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Cardiol. 2025 Jul 1;10(7):678-685. doi:10.1001/jamacardio.2025.0860 IF: 14.1 Q1 .

2. Solomon SD, McMurray JJV, Anand IS, et al. Angiotensin–Neprilysin Inhibition in Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:1609–1620. (PARAGON‑HF)

3. Anker SD, Butler J, Filippatos G, et al. Empagliflozin in Heart Failure with a Preserved Ejection Fraction. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:1451–1461. (EMPEROR‑Preserved)

4. Pitt B, Pfeffer MA, Assmann SF, et al. Spironolactone for heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1383–1392. (TOPCAT)

5. Heidenreich PA, Bozkurt B, Aguilar D, et al. 2022 AHA/ACC/HFSA Guideline for the Management of Heart Failure. Circulation. 2022;145:e895–e1032.

Note: Readers seeking further details on trial methods, subgroup definitions, and prespecified statistical plans should consult the primary JAMA Cardiology publication by Desai et al. (2025).