Introduction

A sense of smell is easy to take for granted until it fails. Yet growing evidence shows that changes in smell — from reduced sensitivity (hyposmia) to complete loss (anosmia) and false perceptions (phantosmia) — are more than a nuisance. A large prospective cohort led by the University of East Anglia in collaboration with 12 international research institutions has confirmed a robust association between olfactory abnormalities and at least 139 medical conditions, and suggests that smell loss often appears long before other hallmark symptoms. The findings — with important implications for both primary care and specialty practice — argue that olfactory assessment deserves a place in routine clinical screening. (Reference: Leon M, Troscianko ET, Woo CC. Inflammation and olfactory loss are associated with at least 139 medical conditions. Front Mol Neurosci. 2024 Oct 11;17:1455418.)

This article reviews what the data show, explains likely mechanisms, outlines practical screening and intervention strategies, and offers guidance for clinicians and patients.

What the Data Tell Us

The study mentioned above synthesized prospective cohort data and clinical records to catalog conditions associated with olfactory dysfunction. Key high-level findings are:

– Olfactory abnormalities are associated with at least 139 distinct diagnoses, spanning neurology, otorhinolaryngology (ENT), metabolic and systemic disease, psychiatry, toxic exposures, and genetic disorders.

– Distribution by category in the study: about 41% of associated conditions were neurological; 28% were ENT and respiratory; 21% systemic or metabolic conditions; and 10% other causes including psychiatric disorders, drug- and toxin-related causes, and congenital conditions.

These associations are not merely correlative in every case. For some diseases, smell loss functions as an early sentinel symptom or an independent risk marker:

– Neurodegenerative disease: In Parkinson disease, 60%–80% of patients experience smell loss several years (commonly 3–5) before the motor features such as tremor and rigidity. In Alzheimer disease, olfactory impairment is extremely common — reported rates reach as high as 90% in some cohorts — and the degree of olfactory loss correlates with the pace of cognitive decline.

– Vascular and structural brain disease: Infarcts that affect the frontal or temporal lobes or olfactory tracts can interrupt olfactory pathways and produce smell deficits.

– ENT and respiratory causes: Obstructive or inflammatory lesions of the nasal cavity and olfactory cleft (allergic rhinitis, chronic rhinosinusitis with polyps, nasal tumors), and viral or bacterial infections (including post-viral olfactory dysfunction following influenza or SARS-CoV-2) directly injure the olfactory mucosa.

– Systemic disease: Metabolic and autoimmune disorders — diabetes, hypothyroidism, Sjögren syndrome — can impair olfaction via vascular, inflammatory, or neuropathic mechanisms.

Beyond diagnosis, olfactory loss has prognostic implications. The study and prior literature indicate that olfactory dysfunction is associated with increased all-cause mortality: older adults with impaired smell have an elevated mortality risk (in some analyses roughly 1.5 times that of peers with normal smell), independent of other measured health risks. The mechanism likely reflects olfactory dysfunction as a marker of systemic health and accumulated physiologic decline.

Why Does Smell Fail? Mechanisms Linking Olfaction to Disease

Olfaction is vulnerable because the pathway spans the external environment, peripheral sensory tissue, and central nervous system:

– Peripheral injury and inflammation: The olfactory epithelium sits exposed in the nasal cavity and regenerates throughout life. Inflammatory diseases (rhinitis, sinusitis), viral infections (including SARS-CoV-2), and toxic exposures (solvents, heavy metals) can damage the epithelium and supporting cells, reducing receptor availability.

– Direct epithelial invasion: Certain viruses and bacteria can directly infect or destroy olfactory receptor neurons and sustentacular cells, leading to acute and sometimes chronic dysfunction.

– Neural degeneration and central pathology: Olfactory receptor neurons project directly to limbic and cognitive centers — the olfactory bulb, piriform cortex, amygdala, and hippocampus. Neurodegenerative proteinopathies (alpha-synuclein in Parkinson disease; beta-amyloid and tau in Alzheimer disease) frequently involve olfactory structures early in their course, producing smell loss before other clinical signs.

– Vascular compromise: Small-vessel disease or focal infarcts affecting olfactory pathways can interrupt transmission.

– Immune-mediated and metabolic effects: Autoimmune inflammation, metabolic dysregulation, and systemic inflammation alter neuronal and mucosal function, impairing olfaction indirectly.

This diversity of mechanisms explains why olfactory dysfunction is non-specific but highly informative: it can be an early symptom of local disease (nasal pathology) or a harbinger of systemic or central processes.

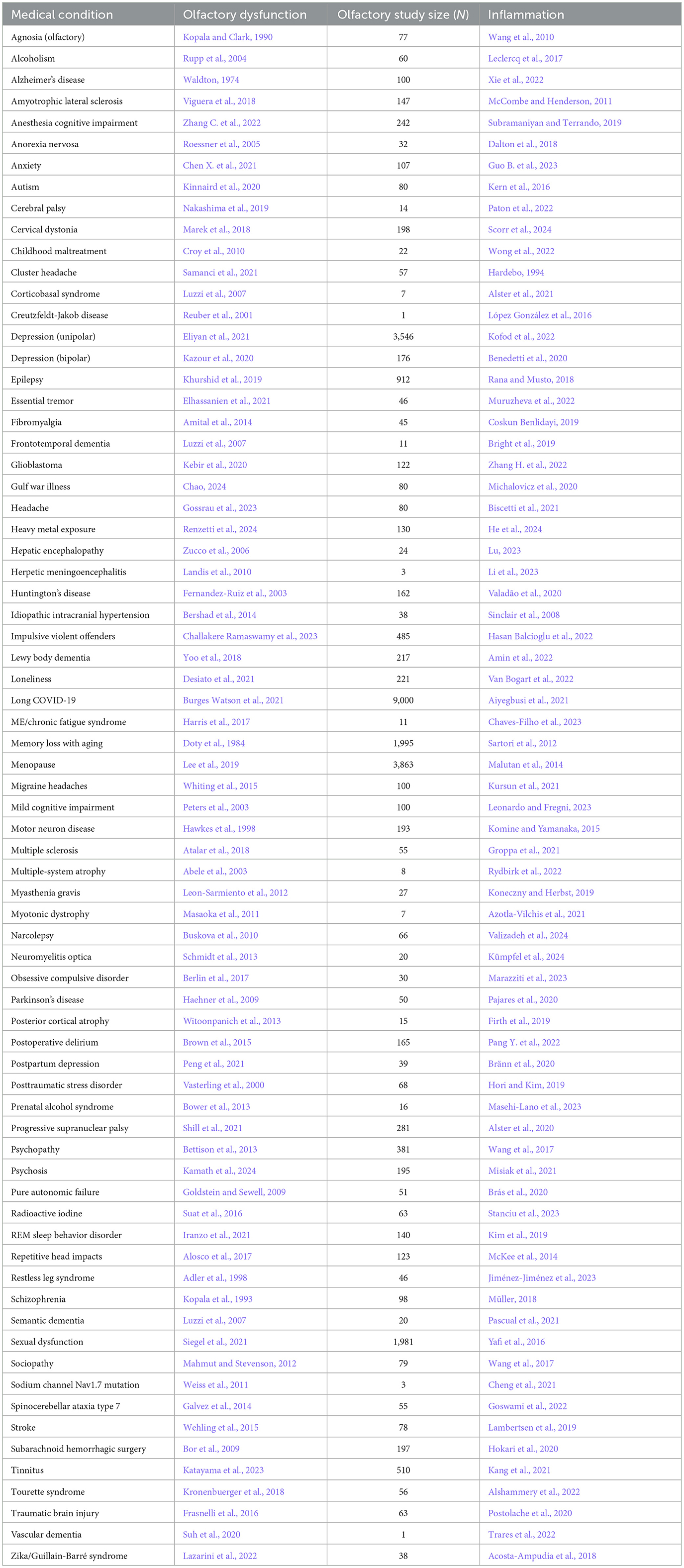

Table 1. Neurological condition/disorder, the reference for accompanying olfactory dysfunction, study size of olfactory study, and reference for inflammation.

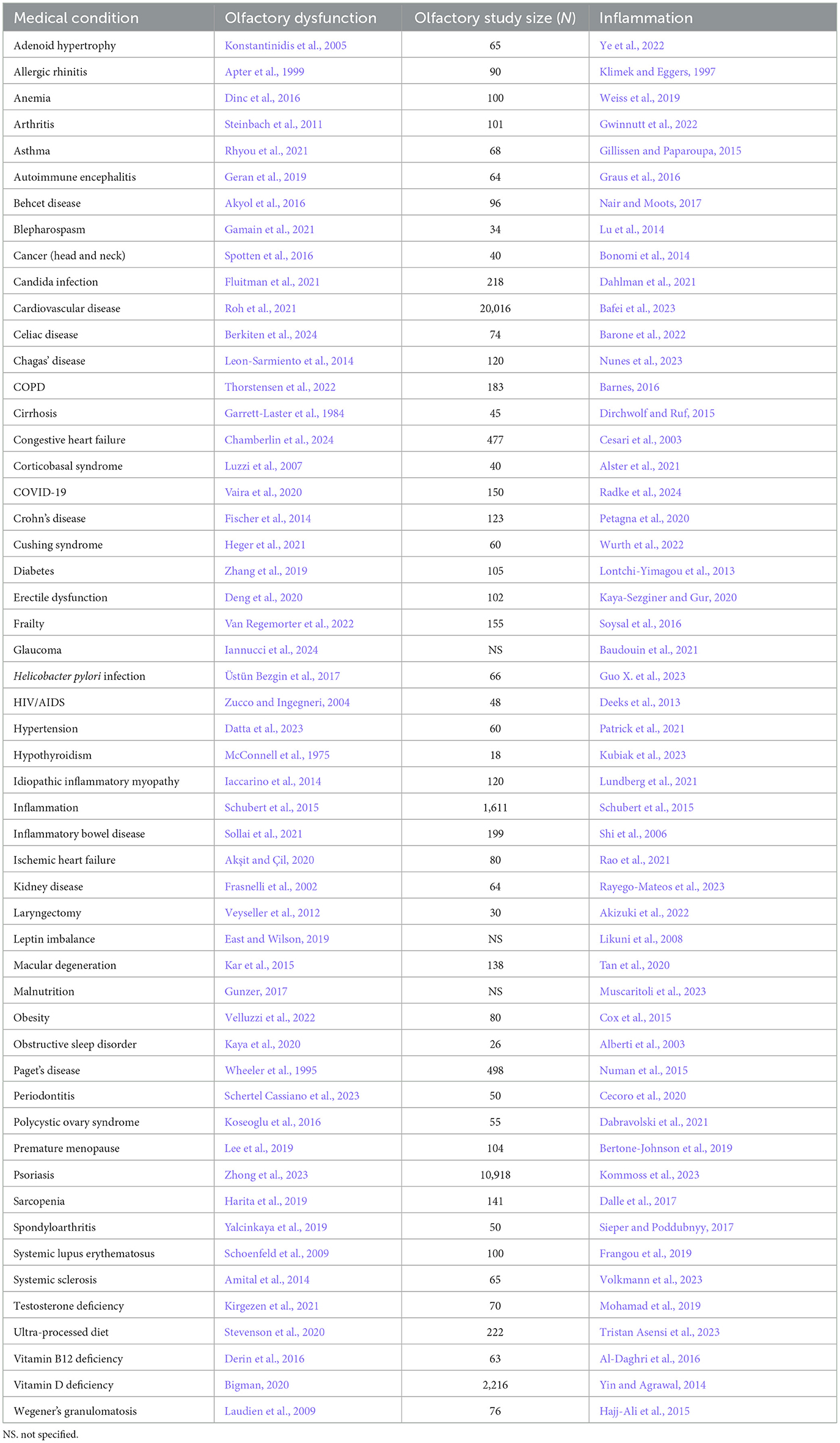

Table 2. Somatic condition/disorder, the reference for accompanying olfactory dysfunction, study size of olfactory study, and reference for inflammation.

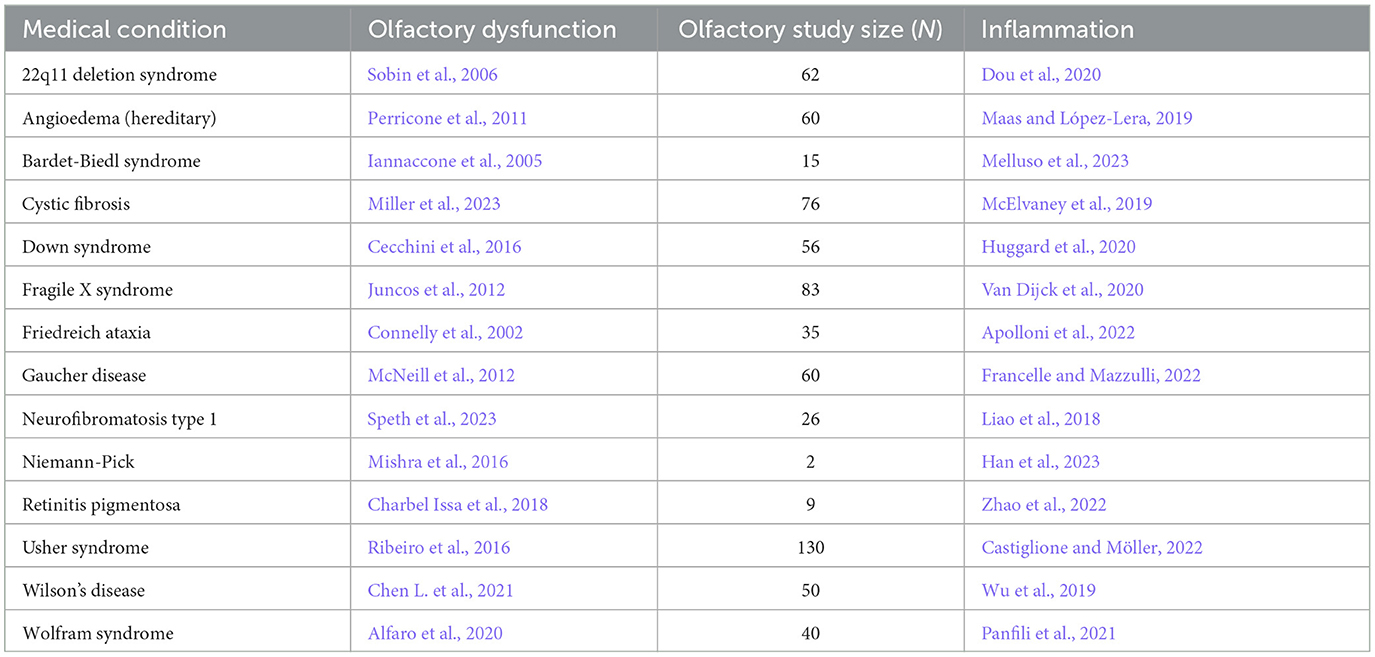

Table 3. Congenital/hereditary disorder, the reference for accompanying olfactory dysfunction, study size of olfactory study, and reference for inflammation.

Clinical Value: When to Take a Complaint About Smell Seriously

Smell complaints often go unreported — patients may adjust to anosmia, or clinicians may prioritize other systems. Yet a structured approach can identify high-yield situations:

When to investigate promptly

– New-onset anosmia or severe hyposmia without obvious transient cause (e.g., heavy nasal congestion that resolves) should trigger further evaluation.

– Smell loss accompanied by other red flags — progressive cognitive symptoms, new motor signs, unexplained weight loss, persistent nasal bleeding, focal neurologic deficits — deserves urgent work-up.

– Persistent post-infectious smell loss (for example, months after respiratory viral infection) merits ENT referral and consideration of smell training and specialist diagnostics.

Populations who should be screened

– Adults aged 45 and older (age-related decline rises with age).

– People with family history of neurodegenerative disease (Parkinson or early-onset Alzheimer disease).

– Patients with chronic nasal disease, persistent upper respiratory infections, diabetes, autoimmune disease, or chronic exposure to inhalational toxins.

– People reporting qualitative olfactory disorders: distorted smell (parosmia) or phantom smells (phantosmia).

Practical Smell Assessment: Simple and Clinic-Friendly

Screening can be pragmatic and low-cost:

Subjective screening

– Brief questions embedded in annual reviews: “Have you noticed a reduction in your sense of smell?” “Can you smell coffee, cooking, or smoke?”

– Standardized questionnaires can improve detection in busy settings.

Objective bedside tests

– Odor identification tools (“sniffin’ sticks” or simple odorant pens): present familiar odors (rose, lemon, coffee, clove/pepper) for identification or recognition. Scoring systems classify normal, hyposmia, or anosmia.

– Threshold and discrimination tests are available in clinics with more resources.

Suggested frequency

– For at-risk groups (age >45, chronic nasal disease, family history), an annual smell screen is reasonable. New or worsening symptoms should trigger earlier evaluation.

Limitations

– Nasal congestion or acute infectious symptoms can transiently impair smell and should be re-assessed after resolution.

– Cultural differences in odor familiarity mean tests should use locally familiar scents or validated cross-cultural sets.

Intervention and Rehabilitation: What Works

Addressing olfactory dysfunction begins with etiology-directed care.

Treat the cause

– ENT conditions: chronic rhinosinusitis with polyps, significant septal deviation, or tumors may require topical or systemic corticosteroids, surgery, or tumor-directed therapies.

– Infections: management ranges from supportive care for common viral infections to targeted therapy for bacterial sinusitis.

– Medication review: several drugs (some antibiotics, antihistamines, antineoplastic agents) can diminish smell; consider alternatives where feasible.

– Systemic disease control: optimize glycemic control, thyroid replacement, and manage autoimmune activity.

Olfactory training

– Evidence supports structured olfactory training (daily, repeated exposure to a small set of distinct odors) for many post-viral and idiopathic olfactory disorders.

– A widely used protocol: four odors (for example, lemon/citrus, rose, eucalyptus, clove) sniffed for 10–15 seconds each, twice daily, for 3–6 months or longer. Improvements can accrue slowly but are reproducible across trials.

Adjunctive therapies

– Topical intranasal corticosteroids can benefit patients with inflammatory nasal disease.

– Supportive strategies: humidification or saline irrigations for dry mucosa (for example in Sjögren syndrome) and smoking cessation to reduce ongoing insult.

Emerging and investigational approaches

– Neurorehabilitation and neuromodulation are under study; regenerative strategies for olfactory neurons are an active research area but not yet standard practice.

Misconceptions and Harmful Assumptions

– “Smell loss is always temporary and trivial”: False. While many post-viral smell losses improve, a significant minority remain impaired, and smell loss can be an early sign of more serious disease.

– “Only ENT problems cause smell loss”: False. The causes range from local nasal disease to central neurodegeneration and systemic illnesses.

– “Smell testing is expensive and impractical”: False. Simple bedside identification tests and brief questionnaires capture many clinically relevant cases and cost little.

Expert Recommendations and Practical Advice

For clinicians

– Include a short smell-screen question in routine reviews for middle-aged and older adults and those with relevant risk factors.

– When smell loss is new, unexplained, persistent, or accompanied by worrying systemic or neurologic signs, proceed to ENT evaluation and consider neurologic assessment.

– Use olfactory training and address reversible causes before labeling anosmia as irreversible.

For patients

– Note and report changes: sudden inability to smell smoke or gas is an immediate safety concern.

– If smell loss follows a cold or COVID-19 and persists past 4–6 weeks, ask for a referral to ENT or a clinic experienced in smell testing.

– Try olfactory training as a low-risk, low-cost intervention; combine it with lifestyle steps: stop smoking, avoid toxic inhalants, keep nasal passages moist.

Patient Vignette: A Practical Illustration

Michael Davis, 58, comes to his primary care clinic for an annual review. He reports that over the past 18 months he has noticed foods taste “bland” and he cannot smell freshly brewed coffee, but he attributed it to aging. On review, he mentions mild constipation and occasional stiffness but no tremor. His clinician performs a quick odor identification screen and documents moderate hyposmia. Given Michael’s age and subtle motor complaints, the clinician arranges an ENT assessment to exclude nasal causes and refers to neurology for baseline cognitive and motor evaluation and counseling about Parkinson disease risk. Michael begins olfactory training and is monitored longitudinally; early detection allows counseling, surveillance, and potential enrollment in research studies about prodromal Parkinson disease.

Gaps, Research Directions and Public Health Implications

Key knowledge gaps include the best methods and frequency for routine olfactory screening, biomarkers that distinguish reversible from progressive causes, and scalable rehabilitation techniques. Public health implications are substantial: smell testing is a low-cost tool that could be integrated into preventive care workflows to flag early neurodegenerative disease, environmental exposures, and unmet ENT pathology.

Conclusion

Smell is a sentinel sense. Olfactory abnormalities associate with at least 139 medical conditions and can serve as an early warning system for neurological, ENT, systemic, and toxic causes. Clinicians should add a brief smell history and simple testing to routine care for middle-aged and older adults and for people with risk factors. For many patients, targeted treatment and olfactory training can improve outcomes; for others, smell loss provides a crucial early clue that prompts further investigation and preventive care.

Funding and clinicaltrials.gov

The primary manuscript referenced notes multi-institutional collaboration; individual funding sources were acknowledged in that publication. For specific trials of olfactory rehabilitation or disease-modifying therapies in neurodegeneration, consult clinicaltrials.gov and specialty trial registries for up-to-date listings.

References

Leon M, Troscianko ET, Woo CC. Inflammation and olfactory loss are associated with at least 139 medical conditions. Front Mol Neurosci. 2024 Oct 11;17:1455418. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2024.1455418 IF: 3.8 Q2 . PMID: 39464255 IF: 3.8 Q2 ; PMCID: PMC11502474 IF: 3.8 Q2 .

(Additional high-quality reviews and disease-specific guidelines on olfactory dysfunction are available through specialty societies in otorhinolaryngology and neurology.)