Introduction: The Persistent Challenge of Ischemic Time

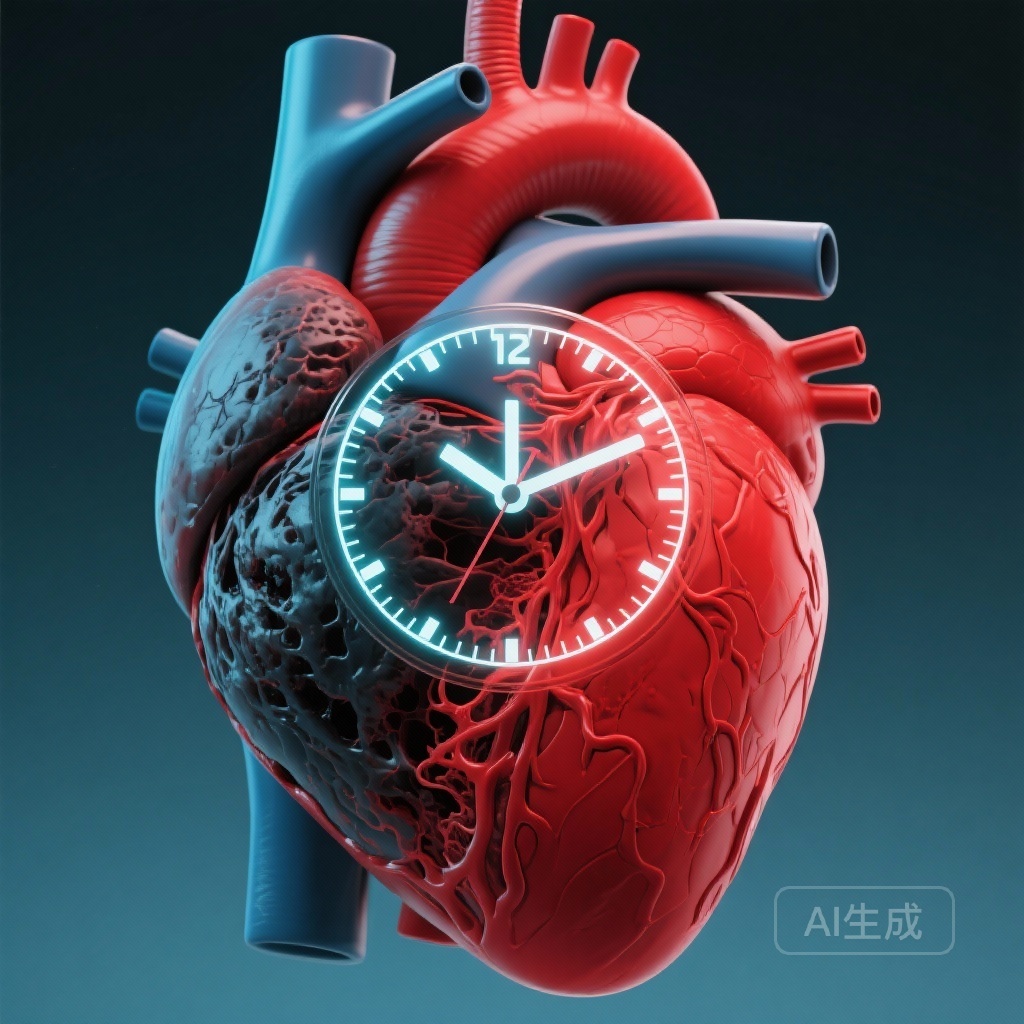

In the management of ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), the mantra ‘time is muscle’ has guided clinical practice for decades. Total ischemic time—the duration from the onset of symptoms to the restoration of coronary blood flow—is a primary determinant of myocardial salvage and subsequent clinical outcomes. While healthcare systems have made significant strides in reducing ‘system delays,’ such as door-to-balloon times, the ‘pre-hospital delay’ (the time from symptom onset to hospital arrival) remains a complex and stubborn barrier to optimal care. A recent 20-year observational study utilizing the SWEDEHEART registry provides a comprehensive look at how these delays have evolved and their precise impact on patient survival.

Study Design and Population: Two Decades of Data

This study utilized the Swedish Web-system for Enhancement and Development of Evidence-based care in Heart disease Evaluated According to Recommended Therapies (SWEDEHEART) registry, one of the world’s most robust and comprehensive longitudinal databases for cardiovascular disease. The researchers analyzed data from 89,155 patients diagnosed with STEMI between 1998 and 2017.

The primary objective was to estimate the associations between pre-hospital delay time and mortality at three distinct intervals: 14 days, 1 year, and 5 years. Using Kaplan-Meier survival curves and multivariable-adjusted Cox regression analyses, the study sought to determine if delay time served as an independent predictor of death, while also exploring temporal trends and demographic disparities across age, sex, and diabetic status.

Key Findings: Quantifying the Mortality Risk

The results underscore a clear and quantifiable relationship between every hour lost before hospital arrival and the risk of death.

Short-Term and Long-Term Prognosis

The study found that the multivariable-adjusted risk of 14-day mortality increased by approximately 2% for every hour of delay (Hazard Ratio [HR] 1.018; 95% Confidence Interval [CI] 1.011-1.025). This prognostic impact persisted into the long term, with 1-year and 5-year mortality risks both increasing by approximately 1% per hour of delay (HR 1.011 and 1.009, respectively). These findings establish pre-hospital delay as a robust, independent predictor of both immediate and extended mortality.

Temporal Trends and the Shift in Care Eras

Over the 20-year study period, the median pre-hospital delay time was 150 minutes (IQR 80–302), and interestingly, no overall declining trend was observed across the two decades. However, a more nuanced analysis revealed a ‘hump-shaped’ curve. During the ‘fibrinolytic era’ (1998–2004), pre-hospital delay times actually increased significantly. Conversely, during the ‘primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PPCI) era’ (2005–2017), delay times showed a promising decrease. This suggests that the shift toward more centralized and specialized cardiac care may have indirectly influenced patient or system behaviors regarding time-to-hospitalization.

The Demographic Gap: Vulnerable Populations

One of the most significant findings of the study relates to the persistent disparities in delay times among specific patient subgroups. Women, the elderly (aged >70 years), and patients with diabetes mellitus consistently exhibited longer pre-hospital delays—averaging 25 to 30 minutes more than their counterparts.

Biological and Social Factors

These delays are likely multifactorial. Women and patients with diabetes are more likely to present with ‘atypical’ symptoms, such as shortness of breath, fatigue, or epigastric pain, rather than the classic substernal chest pressure. This can lead to a failure to recognize the urgency of the situation, both by the patient and by initial healthcare contacts. In elderly populations, cognitive factors, social isolation, or a higher threshold for seeking medical assistance may contribute to the prolonged delay.

Expert Commentary: Clinical and Public Health Implications

The SWEDEHEART data confirms that while we have optimized what happens inside the hospital, we are failing to adequately address what happens before the patient arrives. The 2% increase in 14-day mortality per hour is a stark reminder that pre-hospital delay is not just a logistical metric but a biological determinant of survival.

The Role of Public Awareness

Clinical guidelines emphasize that patients should call emergency medical services (EMS) immediately upon suspicion of a myocardial infarction. However, the lack of improvement in delay times over 20 years suggests that public education campaigns may need to be more targeted. Specifically, campaigns must move beyond ‘chest pain’ education and include the broader spectrum of symptoms experienced by women and diabetics.

Limitations and Generalizability

While the SWEDEHEART registry is highly representative of the Swedish population, the findings may vary in countries with different geographic challenges or healthcare structures. Additionally, the study is observational, meaning that while it shows a strong association between delay and mortality, other unmeasured confounding factors could influence the outcomes. However, the biological plausibility of the ‘time is muscle’ hypothesis strongly supports the causal nature of these findings.

Conclusion: A Call for Targeted Intervention

Pre-hospital delay remains a critical, independent predictor of mortality in STEMI. While the reduction in delay during the PPCI era is encouraging, the lack of overall progress over 20 years and the persistent gaps for women, the elderly, and those with diabetes are concerning. Future interventions must focus on these high-risk groups, improving symptom recognition and streamlining the transition from the community to the catheterization lab. Reducing pre-hospital delay is perhaps the most significant remaining opportunity to further reduce the global burden of STEMI-related mortality.

References

1. Ericsson M, Alfredsson J, Strömberg A, Thylén I, Sederholm Lawesson S. Temporal trends and prognostic impact of pre-hospital delay in ST-elevation myocardial infarction – 20-year observational study from the SWEDEHEART registry. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care. 2025; zuaf165.

2. Ibanez B, et al. 2017 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation. Eur Heart J. 2018;39(2):119-177.

3. Vogel B, et al. The Lancet women and cardiovascular disease Commission: reducing the global burden by 2030. Lancet. 2021;397(10292):2385-2438.