Highlights

– In-hospital pediatric cardiac arrest (IHCA) presents unique physiologic and logistic challenges that limit direct translation of adult resuscitation strategies.

– Recent registry and trial data show declining intra‑arrest intubation rates, no overall survival benefit or harm after time‑dependent matching, and a potential age‑dependent benefit for intubation in children ≥8 years.

– Nearly half of children with initially shockable IHCA receive epinephrine before first defibrillation; adjusted analyses show no statistically significant harm, but observational bias remains a concern.

– A large multicenter randomized quality‑improvement trial of frequent point‑of‑care CPR training plus physiologic debriefing (ICU‑RESUS) did not improve survival with favorable neurologic outcome, underscoring complexity of improving outcomes in pediatric IHCA.

Background and disease burden

Pediatric in‑hospital cardiac arrest (IHCA) remains a high‑stakes, relatively uncommon event with substantial morbidity and mortality. Contemporary registry data estimate survival to discharge around 40% overall, but outcomes vary widely by age, illness category, location, and initial rhythm. Pediatric physiology — smaller airway diameters, higher baseline heart rates, greater metabolic rate, and different arrest etiologies (respiratory failure and asphyxia are more common than primary cardiac arrhythmia) — complicates direct extrapolation from adult resuscitation science. Practical aspects of pediatric resuscitation (team composition, equipment sizing, vascular access, and airway management) further differentiate care.

Clinicians face key unresolved questions during pediatric IHCA: should the team prioritize early tracheal intubation, when and whether to give epinephrine relative to defibrillation in shockable rhythms, and can intensive training and physiologic feedback reliably change bedside performance and patient outcomes? Three recent multicenter investigations using large registry data or randomized designs provide contemporary evidence to inform these debates.

Study designs and populations

This synthesis draws on three complementary studies derived from the American Heart Association Get With The Guidelines‑Resuscitation registry and the ICU‑RESUS randomized trial network:

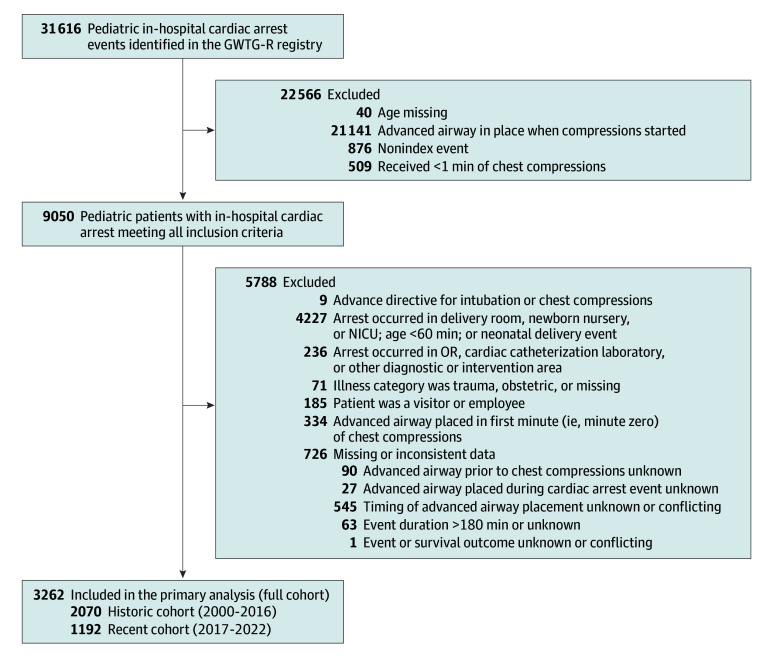

- Intubation Trends and Survival in Pediatric IHCA (Shepard et al., JAMA Network Open, 2025): retrospective cohort of pediatric IHCA from 2000–2022; focused time‑dependent propensity matched analysis for 2017–2022 cohort with patients who had no advanced airway at CPR onset.

- Epinephrine Before Defibrillation in Children With Initially Shockable IHCA (Swanson et al., Crit Care Med, 2025): retrospective cohort of children with initial VF/pulseless VT (2000–2020 registry data); exposure was epinephrine given before or during same minute as first defibrillation; propensity matching with exact matching on time to defibrillation.

- ICU‑RESUS (Sutton et al., JAMA, 2022): a parallel hybrid stepped‑wedge, cluster randomized trial across 18 pediatric ICUs testing a bundled intervention (frequent point‑of‑care physiologic CPR training and structured event debriefing) versus usual care, with index CPR events followed to hospital discharge.

Key findings — airway management

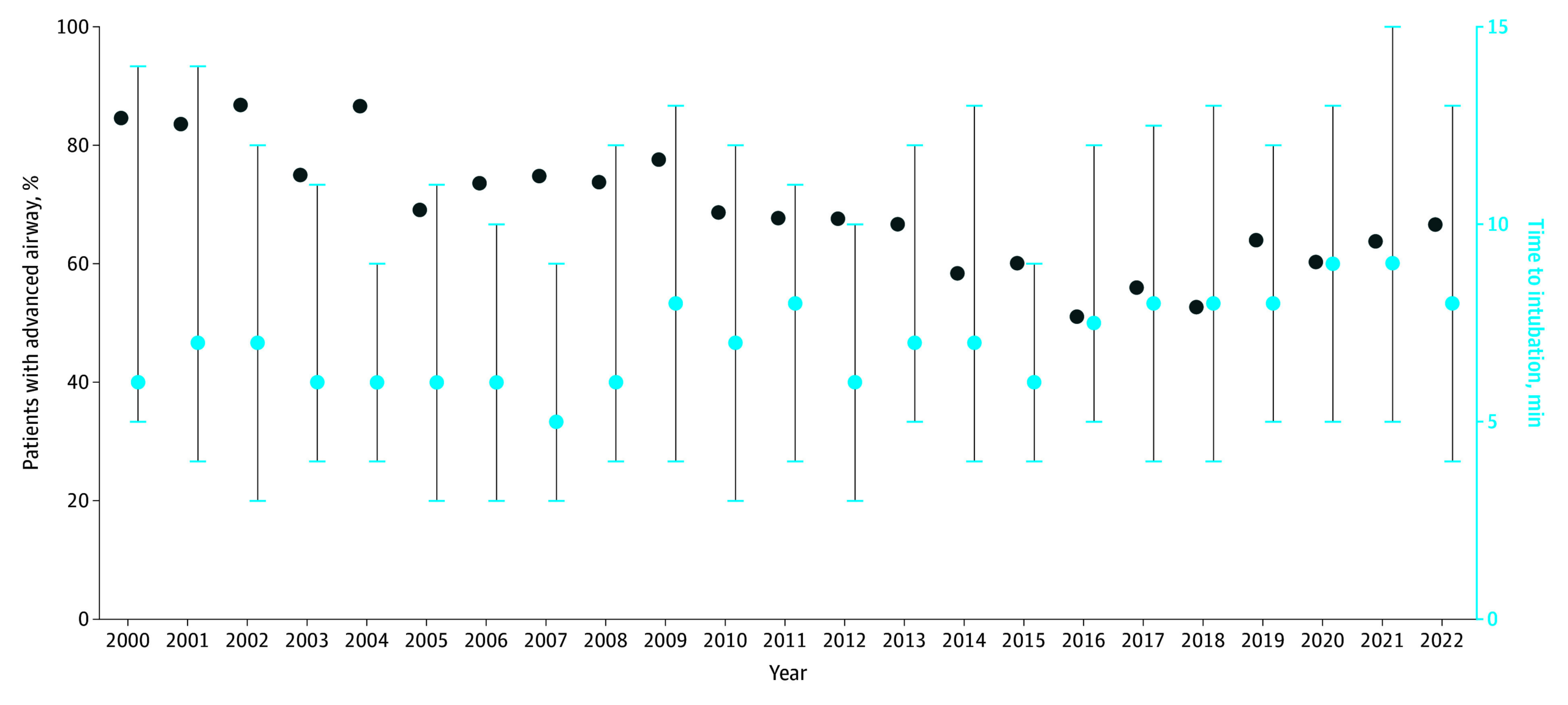

Shepard and colleagues analyzed 3,262 pediatric IHCA events without an advanced airway at CPR onset. Overall intubation during arrest declined from the early 2000s to 2022 (e.g., 84.6% in 2000 vs 66.7% in 2022; trend P < .001). In the contemporary 2017–2022 cohort, unadjusted analyses showed markedly lower survival to discharge when intubation occurred during arrest (OR 0.18, 95% CI 0.14–0.24). However, a rigorous time‑dependent propensity score matching—which accounts for changing risk over minutes of CPR and matches each intubated patient to patients still at risk in the same minute—removed that association (adjusted OR 1.18, 95% CI 0.90–1.53; P = .23).

Notably, subgroup analysis by age revealed that for children ≥8 years, intra‑arrest intubation was associated with higher odds of survival (adjusted OR 1.91, 95% CI 1.09–3.33; P = .02). This age effect suggests physiologic and technical differences across pediatric age strata: older children have larger airways, adult‑sized anatomy permitting more reliable intubation, and arrest etiologies more similar to adults (primary arrhythmia), potentially making advanced airway benefits more likely.

Clinical interpretation: time‑dependent confounding (sicker patients are more likely to be intubated later in a prolonged arrest) explains much of the crude association between intubation and worse outcomes. Contemporary matched analyses suggest neutrality overall, with a possible benefit in older children. Decisions about airway strategy should prioritize uninterrupted high‑quality chest compressions and team competence in whichever airway approach they perform reliably (bag‑mask ventilation vs supraglottic airway vs tracheal tube), with selective consideration of intubation in older pediatric patients when it can be accomplished without prolonged peri‑procedural pauses.

Key findings — epinephrine timing and shockable rhythms

Among 492 children with an initial shockable rhythm, nearly half (47%) received epinephrine before or during the same minute as first defibrillation—contrary to guideline emphasis on prompt defibrillation in shockable arrests. Unadjusted outcomes were worse in the epinephrine‑first group (survival to discharge 37.1% vs 51.2%; ROSC 74.6% vs 84.6%; favorable neurologic outcome 22.1% vs 40.4%). However, after propensity score matching with exact matching on time to defibrillation, epinephrine given before or concomitant with defibrillation was not significantly associated with lower survival (OR 0.84, 95% CI 0.46–1.56) or ROSC, and had a borderline result for neurologic outcome (OR 0.52, 95% CI 0.27–1.00).

Clinical interpretation: observationally worse outcomes when epinephrine precedes defibrillation are concerning, but confounding by arrest severity and delays to definitive rhythm conversion likely explains much of this difference. The adjusted null findings do not validate routine epinephrine ahead of defibrillation; they indicate that, within current practice variability, a clear causal harm is not established. Current guidelines still prioritize immediate defibrillation for shockable pediatric arrests, and teams should avoid epinephrine administration that delays first shock.

Key findings — training, physiologic targets, and ICU‑RESUS

The ICU‑RESUS randomized trial tested a pragmatic, scalable bundle: frequent brief, point‑of‑care CPR practice sessions on manikins plus structured, physiologically focused post‑event debriefings. The bundle sought to improve attainment of intra‑arrest diastolic blood pressure targets during CPR and systolic blood pressure after ROSC—physiologic mediators associated with outcome in observational studies.

Among 1,129 index ICU CPR events, the intervention did not significantly increase survival to discharge with favorable neurologic outcome (53.8% intervention vs 52.4% control; adjusted OR 1.08, 95% CI 0.76–1.53) nor overall survival to discharge. The neutral result persisted despite the trial’s rigorous design and physiological rationale.

Clinical interpretation: high‑frequency training and structured debriefing are attractive and feasible QI measures, but translating improved process measures into patient‑level outcome gains is difficult. Potential explanations include high baseline performance at participating centers (ceiling effects), insufficient dose or fidelity of training to alter complex team dynamics under stress, and the multifactorial determinants of survival beyond CPR mechanics (etiology, comorbidities, preexisting organ failure).

Expert commentary and mechanistic considerations

Integrating these studies suggests three key themes. First, pediatric IHCA outcomes are highly age‑dependent and driven by arrest etiology; interventions effective in adults or older children may not generalize to infants and younger children. Second, observational associations (e.g., worse outcomes with intra‑arrest intubation or epinephrine before defibrillation) are vulnerable to time‑dependent confounding; analytic approaches that match on risk at each minute of CPR or on time to defibrillation strengthen causal inference but cannot replace randomized evidence. Third, training and debriefing programs need to be optimized for transfer to real events and targeted to modifiable physiologic mediators; enhancing performance metrics alone may be insufficient.

Mechanistically, intubation can be beneficial by securing the airway and facilitating controlled ventilation, but may interrupt chest compressions and delay other critical steps if not performed seamlessly. In infants, bag‑mask ventilation can be effective and faster; in older children, definitive airway control may improve oxygenation and ventilation without compromising compressions if performed by experienced providers. Epinephrine increases coronary perfusion pressure via vasoconstriction, which can aid ROSC, but may increase myocardial oxygen demand and theoretically reduce the efficacy of defibrillation if given before a shock—though existing adjusted observational data do not confirm a consistent harmful effect. Lastly, physiologically targeted CPR (for example, diastolic BP thresholds) is promising, but implementing continuous arterial BP monitoring and real‑time adjustments during arrests is technically and operationally challenging.

Limitations and generalizability

Key limitations across studies include reliance on registry data with variable completeness, potential residual confounding despite advanced matching techniques, and limited power for some subgroup analyses and neurologic outcomes. ICU‑RESUS, although randomized, tested a bundled QI intervention where fidelity and center effects may have influenced results. Participating centers in all studies are often tertiary care hospitals with established resuscitation programs, which may limit generalizability to smaller centers.

Conclusion and clinical implications

Recent high‑quality multicenter research refines but does not radically change current pediatric IHCA practice: prioritize uninterrupted high‑quality chest compressions, ensure timely defibrillation for shockable rhythms, and avoid procedural or medication delays that meaningfully prolong hands‑off time. Intra‑arrest intubation should not be performed reflexively; teams should weigh patient age, arrest etiology, operator skill, and likely interruptions. For children ≥8 years, selective intubation may confer benefit. Epinephrine before defibrillation remains common in practice but lacks robust evidence of causal harm after adjustment; adherence to guideline priorities (immediate defibrillation) remains reasonable.

Investments in training remain essential, but ICU‑RESUS shows that frequency alone is not enough—training must demonstrably change physiologic performance during real events, and pragmatic trials with physiologic endpoints should inform future QI strategies.

Future research priorities include randomized trials comparing airway strategies (bag‑mask vs supraglottic vs tracheal intubation) stratified by age, pragmatic studies testing epinephrine timing in shockable pediatric arrests, and interventions that enable real‑time physiologic targeting (arterial waveform‑guided CPR) with assessment of patient‑centered outcomes.

Funding and trial registration

ICU‑RESUS was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and related collaborative networks; trial registration: ClinicalTrials.gov NCT02837497. The registry studies used data from the American Heart Association Get With The Guidelines‑Resuscitation registry. See individual publications for full funding disclosures.

References

1. Shepard LN, Reeder RW, Hsu J, et al. Intubation Trends and Survival in Pediatric In‑Hospital Cardiac Arrest. JAMA Netw Open. 2025;8(11):e2544365. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2025.44365 IF: 9.7 Q1 .

2. Swanson MB, Lasa JJ, Chan PS, et al. Epinephrine Before Defibrillation in Children With Initially Shockable In‑Hospital Cardiac Arrest. Crit Care Med. 2025;53(10):e2005‑e2015. doi:10.1097/CCM.0000000000006804 IF: 6.0 Q1 .

3. Sutton RM, Wolfe HA, Reeder RW, et al.; ICU‑RESUS Investigators. Effect of Physiologic Point‑of‑Care Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation Training on Survival With Favorable Neurologic Outcome in Cardiac Arrest in Pediatric ICUs: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2022;327(10):934‑945. doi:10.1001/jama.2022.1738 IF: 55.0 Q1 .

4. American Heart Association. Pediatric Advanced Life Support (PALS) Guidelines. Circulation. 2020;142(16_suppl_2):S641‑S668. (2020 AHA Guidelines for CPR and ECC).