The Hidden Challenge of Whooping Cough

Pertussis, commonly known as whooping cough, remains one of the world’s most persistent public health challenges. Despite decades of widespread childhood vaccination, this highly contagious respiratory disease, caused by the bacterium Bordetella pertussis, continues to cause significant morbidity and mortality, particularly in infants too young to be fully immunized. While our current generation of vaccines—specifically the acellular pertussis vaccines used in most developed nations—are excellent at preventing severe disease, they have a critical Achilles’ heel: they are not very good at preventing infection and transmission.

This means that even vaccinated individuals can become asymptomatic carriers of the bacteria, inadvertently spreading it to vulnerable populations. The scientific community has long recognized that to truly control pertussis, we need a vaccine that induces ‘mucosal immunity’—protection right where the bacteria first land: in the nose and throat. A recent Phase 2b trial published in The Lancet Microbe suggests we may finally have a candidate that can do just that.

A Case Study: The Silent Spread

Consider the case of James, a 30-year-old software engineer living in London. James is a healthy, active individual who stays up-to-date with his vaccinations. When his sister gave birth to a daughter, Lily, James was thrilled to visit. He had no symptoms—no cough, no fever, no runny nose. However, a week after his visit, infant Lily began to experience the characteristic ‘whoop’ of pertussis and had to be hospitalized.

Investigations later suggested that James had been a silent carrier. His childhood vaccines and adult boosters protected him from getting sick, but they didn’t stop the bacteria from colonizing his upper respiratory tract. This scenario is exactly what researchers are hoping to eliminate with the development of the BPZE1 vaccine. By targeting the point of entry, we can protect the individual and the community simultaneously.

Why Current Vaccines Aren’t Enough

To understand the importance of the BPZE1 trial, we must first look at the limitations of current injectable vaccines. Most modern pertussis vaccines are ‘acellular,’ meaning they contain only specific parts of the bacteria to stimulate an immune response. These vaccines are administered via an intramuscular injection. While they generate strong levels of antibodies in the bloodstream (IgG), they are less effective at generating secretory IgA antibodies, which are the primary defenders of the mucosal surfaces in the airway.

Furthermore, the immunity provided by these vaccines wanes relatively quickly, leading to a resurgence of cases among adolescents and adults. This ‘waning immunity’ and the lack of mucosal protection create a reservoir of the bacteria within the population, allowing pertussis to circulate even in communities with high vaccination rates.

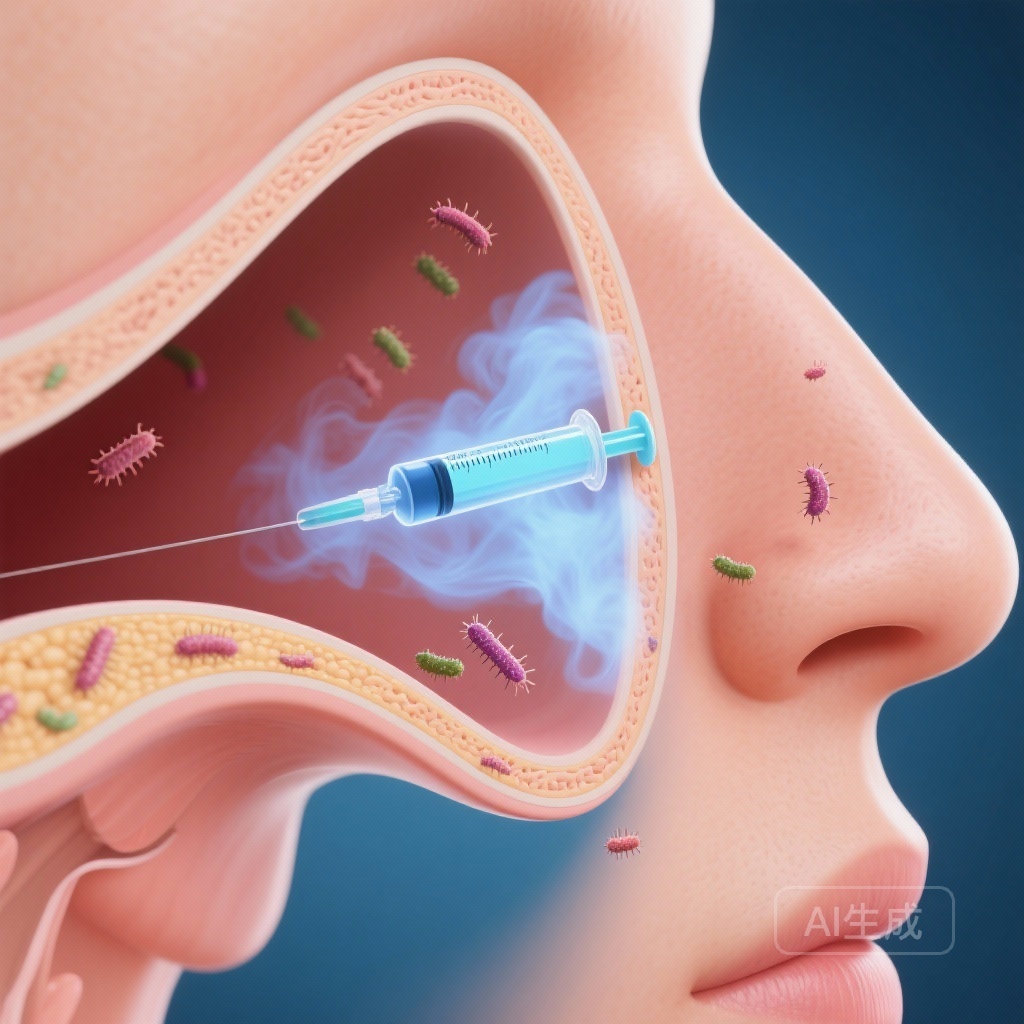

The Science of BPZE1: A Live Attenuated Approach

BPZE1 is a live attenuated vaccine. Unlike acellular vaccines, it contains the entire Bordetella pertussis bacterium, but the organism has been genetically modified to remove or reduce its toxic components. Specifically, three major toxins (pertussis toxin, tracheal cytotoxin, and dermonecrotic toxin) have been either inactivated or removed.

Because BPZE1 is administered as a nasal spray, it mimics a natural infection but without the risk of disease. This route of delivery is designed to train the immune system to recognize and fight the bacteria at the mucosal level. If successful, this would prevent the bacteria from ever establishing a foothold in the respiratory tract, effectively ‘slamming the door’ on infection before it can start.

Inside the Trial: The Controlled Human Infection Model

In this Phase 2b trial conducted at University Hospital Southampton and the University of Oxford, researchers utilized a ‘Controlled Human Infection Model’ (CHIM). This is a sophisticated and highly regulated type of study where healthy volunteers are intentionally exposed to a pathogen in a safe, clinical environment to test the efficacy of a vaccine or treatment.

For this study, 53 healthy adults aged 18 to 50 were recruited. These participants were screened to ensure they did not have high baseline levels of pertussis antibodies, which might interfere with the results. They were then randomly assigned to receive either a single intranasal dose of BPZE1 or a placebo. Between 60 to 120 days after vaccination, the participants were ‘challenged’—meaning they were given a dose of virulent, live Bordetella pertussis via the nose.

What the Data Tell Us: Efficacy and Colonization

The primary goal of the study was to see if BPZE1 could prevent the bacteria from colonizing the nose. Researchers measured this by taking nasal washes on several days following the challenge and attempting to culture the bacteria in the lab.

The results were highly encouraging. In the primary analysis group (the modified intention-to-treat population), 58% of those who received BPZE1 showed no detectable colonization on the key testing days (days 9, 11, and 14), compared to only 33% in the placebo group.

When the researchers looked at the ‘per protocol adequate inoculum’ group—those who received the full intended dose of the challenge bacteria—the results were even more striking. In this group, 60% of the BPZE1 recipients remained free of colonization, compared to just 25% of the placebo group. This difference was statistically significant (p=0·033), providing strong evidence that the vaccine works as intended.

| Population Group | BPZE1 Success (No Colonization) | Placebo Success (No Colonization) | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Modified Intention-to-Treat (mITT) | 58% (14 of 24) | 33% (7 of 21) | 0.091 |

| Per Protocol (Adequate Dose) | 60% (12 of 20) | 25% (4 of 16) | 0.033 |

Safety and Tolerability

Safety is a paramount concern for any new vaccine, especially one that uses a live (though weakened) bacterium. The trial found that BPZE1 was very well tolerated. Most participants reported some mild side effects in the week following vaccination, such as a stuffy or runny nose, but these were almost entirely ‘grade 1’ (mild) in severity.

Crucially, there were no serious adverse events reported during the trial. The frequency of unsolicited side effects was similar between the vaccine and placebo groups, suggesting that the vaccine does not introduce significant new risks for healthy adults. This favorable safety profile is a vital hurdle for any vaccine destined for widespread public use.

Expert Insights and Public Health Commentary

Dr. Sarah Thompson, an infectious disease specialist not involved in the study (speaking generally on the field), notes: “The ability to block colonization is the holy grail of pertussis research. If we can stop people from carrying the bacteria, we change the epidemiology of the disease entirely. We move from just protecting the person who gets the shot to protecting the whole community through herd immunity.”

The study authors emphasized that this trial proves the concept that a nasal vaccine can induce the right kind of immunity to prevent virulent infection. While the study was relatively small, the use of the CHIM model allows for very high-quality data from fewer participants than a traditional field trial would require.

The Road Ahead: From Lab to Clinic

While these results are a major milestone, the journey for BPZE1 is not over. The researchers concluded that large Phase 3 trials are now warranted. These larger studies will need to confirm the efficacy of the vaccine in broader, more diverse populations and further establish its long-term safety profile.

If BPZE1 continues to perform well, it could eventually be used as a booster for adults, particularly those who are in contact with infants, or even as part of the primary vaccination schedule for children. The potential to provide a ‘nasal shield’ against pertussis represents one of the most exciting developments in vaccine science in recent years.

Conclusion

The fight against whooping cough is far from over, but the BPZE1 trial offers a beacon of hope. By shifting our focus from merely treating the symptoms of the disease to preventing the very colonization of the bacteria, we may be on the verge of a new era in respiratory health. For people like James and infants like Lily, this science isn’t just about data points—it’s about a future where one of the world’s oldest respiratory threats is finally silenced.

Funding and Clinical Trials

This study was funded by ILiAD Biotechnologies. The trial is registered with ClinicalTrials.gov, number NCT05461131.

Reference

Gbesemete D, Ramasamy MN, Ibrahim M, Hill AR, Raud L, Ferreira DM, Guy J, Dale AP, Laver JR, Coutinho T, Faust SN, Reed TAN, Babbage G, Weissfeld L, Lang W, Locht C, Samal V, Goldstein P, Solovay K, Rubin K, Noviello S, Read RC. Efficacy, immunogenicity, and safety of the live attenuated nasal pertussis vaccine, BPZE1, in the UK: a randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 2b trial using a controlled human infection model with virulent Bordetella pertussis. Lancet Microbe. 2025 Dec;6(12):101211. doi: 10.1016/j.lanmic.2025.101211. Epub 2025 Dec 1. PMID: 41344352.