Understanding the Haemodynamic Heterogeneity of Advanced Conduction Disorders

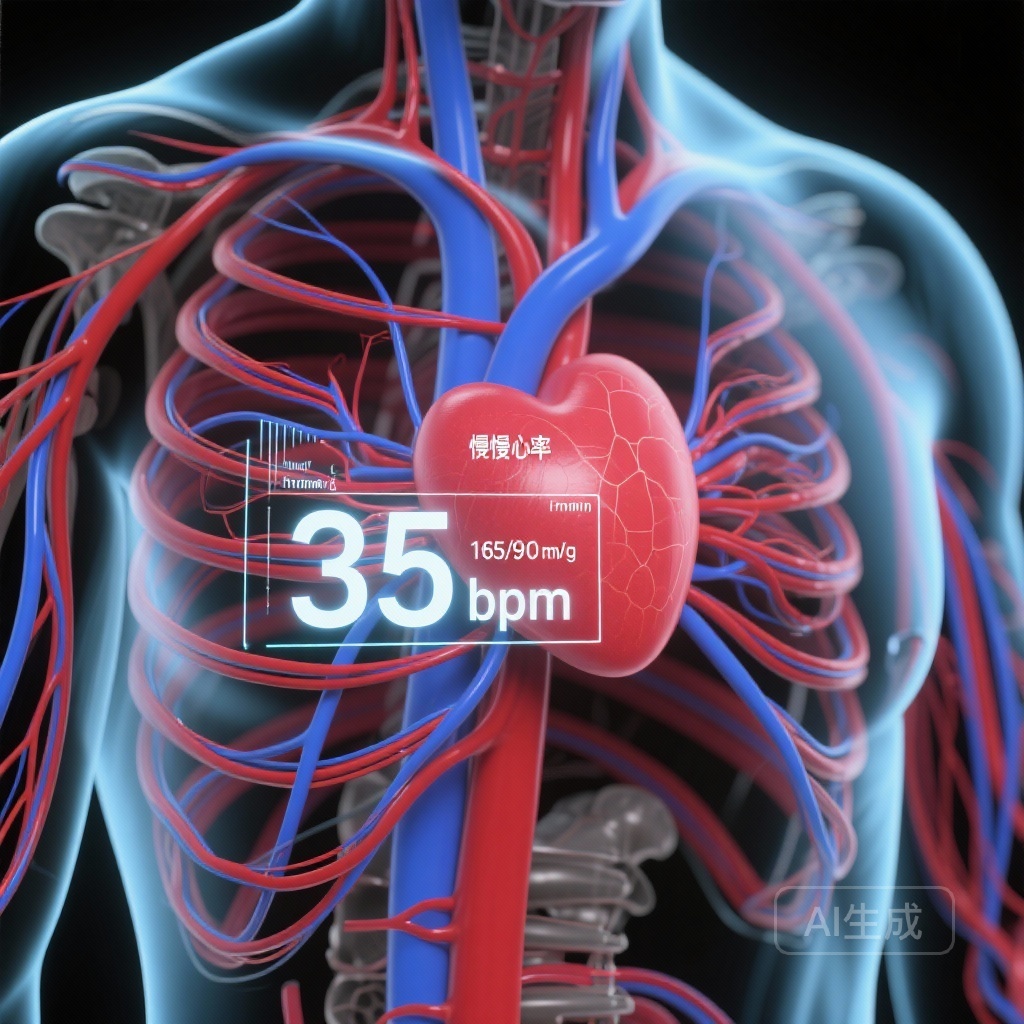

The clinical presentation of patients with advanced conduction disorders, such as high-degree atrioventricular (AV) block, is remarkably diverse. Traditionally, the clinical focus on bradyarrhythmias has been centered on the risks of hypotension, syncope, and cardiogenic shock. However, in emergency departments and cardiac care units, clinicians frequently encounter patients who exhibit a paradox: a significantly low heart rate accompanied by markedly high blood pressure. This hypertensive response is not merely a clinical curiosity but represents a complex physiological adaptation. A recent study by Orvin et al., published in European Heart Journal: Acute Cardiovascular Care, provides a critical analysis of these varying haemodynamic profiles, identifying a distinct hypertensive phenotype that may signal a more resilient compensatory state.

The Clinical Spectrum: From Shock to Hypertension

Advanced conduction disorders interrupt the electrical communication between the atria and ventricles, necessitating an escape rhythm that is typically slow and often unstable. The haemodynamic consequences of this sudden drop in heart rate depend on the body’s ability to maintain cardiac output and systemic perfusion. The study analyzed 261 consecutive patients and categorized them into three distinct groups: normotensive (systolic blood pressure <160 mmHg), hypertensive (systolic blood pressure ≥160 mmHg), and unstable (those requiring emergent temporary pacing due to cardiogenic shock or severe symptoms). The distribution was surprising: while 16.9% were unstable and 37.9% were normotensive, the largest group (45.2%) presented with a hypertensive response. This suggests that hypertension is not an outlier but a common clinical manifestation of high-degree AV block.

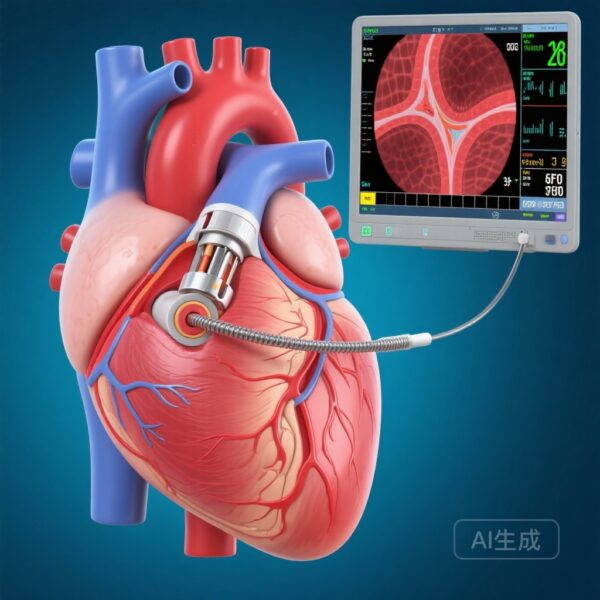

Study Design and Methodology

The researchers conducted a retrospective analysis of patients who underwent pacemaker implantation for advanced conduction disorders at a tertiary medical center between October 2020 and December 2022. To delve deeper into the underlying physiology, a subset of 73 stable patients underwent non-invasive haemodynamic assessment. This assessment utilized advanced technology to measure parameters such as cardiac output, stroke volume, and peripheral vascular resistance (PVR). By comparing these metrics across the normotensive and hypertensive groups, the study aimed to elucidate why some patients compensate effectively while others fail.

Key Findings: The Anatomy of the Hypertensive Phenotype

The study identified several critical factors that differentiate hypertensive patients from their normotensive or unstable counterparts. These findings offer a roadmap for understanding how the body attempts to maintain homeostasis in the face of electrical failure.

Preserved Cardiac Function and Higher Escape Rhythms

Hypertensive patients demonstrated significantly higher left ventricular ejection fractions (58.2 ± 8%) compared to normotensive (53.9 ± 11%) and unstable (53.2 ± 12%) patients. Furthermore, their escape rhythms were more robust, averaging 39.1 beats per minute. This combination of better myocardial contractility and a slightly faster (though still bradycardic) heart rate allows for a more stable baseline from which compensatory mechanisms can operate.

The Role of Peripheral Vascular Resistance (PVR)

One of the most significant findings from the non-invasive haemodynamic evaluation was the role of PVR. The hypertensive group exhibited significantly elevated PVR compared to the normotensive group. This indicates that the primary driver of the hypertensive response in these patients is systemic vasoconstriction. When the heart rate drops, the baroreceptor reflex is triggered, leading to a surge in sympathetic nervous system activity. In patients with the hypertensive phenotype, this sympathetic surge successfully increases vascular tone to maintain mean arterial pressure, albeit at the cost of high systolic readings.

End-Organ Protection and Clinical Outcomes

The clinical benefits of this hypertensive response were evident in the laboratory data. Hypertensive patients showed fewer signs of end-organ hypoperfusion. Specifically, they had lower rates of acute kidney injury and lower serum lactate levels compared to the other groups. Mortality data also reflected this stability; the unstable group faced the highest 30-day mortality, whereas the hypertensive group showed the highest survival rates in the short term. While 1-year mortality trends were also more favorable for hypertensive patients, these did not reach statistical significance, suggesting that while the hypertensive response is protective during the acute event, the underlying cardiovascular health and the successful implantation of a permanent pacemaker are the long-term determinants of survival.

Predictors of the Hypertensive Response

The study identified three independent factors associated with a hypertensive response in the setting of AV block: a higher baseline heart rate, a higher ejection fraction, and pre-treatment with calcium channel blockers (CCBs). The association with CCBs is particularly interesting. While these drugs are often used to treat hypertension, their presence in the patient’s baseline regimen may reflect a pre-existing hypertensive state or a specific vascular profile that predisposes the patient to a robust vasoconstrictive response when cardiac output is challenged.

Expert Commentary and Clinical Implications

The findings by Orvin et al. challenge the simplistic view that all bradycardia should lead to low blood pressure. Instead, they highlight a ‘hypertensive compensation’ that is likely driven by the Frank-Starling mechanism (where increased filling time leads to increased stroke volume) and intensified peripheral resistance.

Triage and Risk Stratification

For clinicians in the emergency department, recognizing this hypertensive phenotype is crucial for risk stratification. A patient presenting with high-degree AV block and a blood pressure of 180/90 mmHg may actually be in a more haemodynamically stable state than a patient with a ‘normal’ blood pressure of 120/80 mmHg, who might be on the verge of failing compensatory mechanisms. This study suggests that the hypertensive response is a marker of physiological reserve.

Mechanistic Insights

The elevated PVR in these patients suggests that the sympathetic nervous system’s response to bradycardia is not uniform. In some patients, the vascular bed is capable of significant constriction to maintain pressure, while in others—perhaps due to autonomic dysfunction or more severe cardiac failure—this response is blunted. Understanding these nuances could eventually lead to more personalized approaches to managing bradyarrhythmias before a permanent pacemaker can be placed.

Conclusion

The haemodynamic response to advanced conduction disorders is highly heterogeneous. The identification of a hypertensive phenotype—characterized by preserved ejection fraction, higher escape rhythms, and increased peripheral vascular resistance—provides valuable insight into the body’s compensatory strategies. This phenotype represents a state of relative haemodynamic resilience, associated with less end-organ damage and better short-term outcomes. Clinicians should view a hypertensive response in the context of bradycardia as a distinct clinical entity that warrants careful observation but may offer a window of relative stability compared to normotensive or unstable presentations.

References

1. Orvin K, et al. Hypertensive vs. normotensive blood pressure response to advanced conduction disorders: comparison of baseline non-invasive haemodynamic evaluation. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care. 2025;14(11):654-663.

2. Kusumoto FM, et al. 2018 ACC/AHA/HRS Guideline on the Evaluation and Management of Patients With Bradycardia and Cardiac Conduction Delay. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;74(14):e51-e156.

3. Brignole M, et al. 2018 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of syncope. Eur Heart J. 2018;39(21):1883-1948.