Highlights

- High-quality randomized trials and cohort analyses revealed no significant longitudinal association between PM2.5 or CO exposure from biomass cooking and severe pneumonia in infants.

- Evidence from the multinational HAPIN trial showed that despite substantial PM2.5 exposure reductions with liquefied petroleum gas (LPG) stoves, incidence of severe infant pneumonia remained unchanged.

- Contrasting earlier observational studies, prenatal CO exposures showed sex-specific associations with pneumonia risk, suggesting complex exposure-response dynamics potentially mediated by infant lung function impairment.

- Insufficient exposure reductions in some interventions and methodological heterogeneity may underlie discrepancies in observed health outcomes, underscoring the need for comprehensive exposure assessment and mechanistic understanding.

Background

Household air pollution (HAP) resulting from biomass fuel combustion for cooking and heating affects approximately 40% of the global population and has been historically implicated as a key environmental risk factor for pediatric respiratory infections, notably pneumonia—the leading cause of death in children under five years. Fine particulate matter (PM2.5) and carbon monoxide (CO) are predominant pollutants generated during incomplete biomass combustion. Pneumonia burden remains high in low- and middle-income countries where biomass is widely used, propelling global efforts toward clean cooking interventions (e.g., LPG stoves) to mitigate exposure and improve child health outcomes.

Despite epidemiological associations between HAP and respiratory morbidity, establishing a definitive causal link, particularly for severe pneumonia in infancy, remains challenging due to potential confounding, exposure misclassification, and diverse environmental and sociodemographic contexts. Recent large-scale randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and refined exposure-response analyses provide new insights, necessitating a systematic synthesis to guide clinical and public health strategies.

Key Content

Chronological Development and Multinational Evidence from Randomized Trials

The Household Air Pollution Intervention Network (HAPIN) trial, conducted from 2018 to 2021 across Guatemala, India, Peru, and Rwanda, represents the largest multinational RCT comparing the respiratory health impact of LPG versus biomass cooking during pregnancy and infancy (McCracken et al., 2025, JAMA Netw Open). This 18-month intervention distributed LPG stoves and fuel, with repeated 24-hour personal exposure measurements of PM2.5 and CO in pregnant women and their infants.

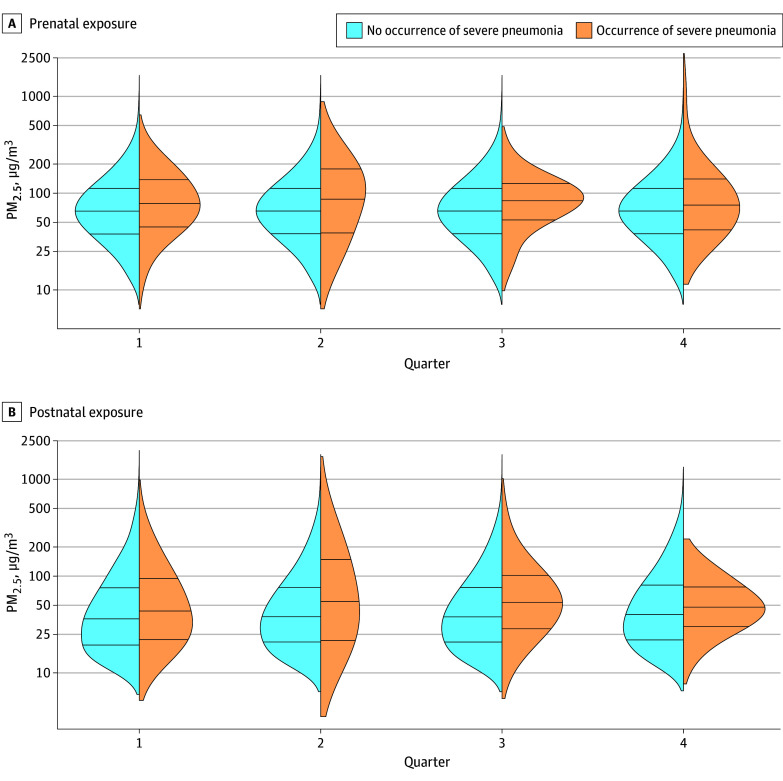

The primary outcome—severe pneumonia in infants during the first year of life—was rigorously defined with clinical signs confirmed by imaging and hypoxemia measured by pulse oximetry. Among 3061 infants, despite a broad range of PM2.5 exposures (5.4–1182 µg/m³), no statistically significant association was observed between prenatal or postnatal PM2.5 exposure levels and severe pneumonia incidence, with adjusted risk ratios near unity (prenatal RR 1.03, 95% CI 0.94–1.13; postnatal RR 0.97, 95% CI 0.87–1.09). Likewise, CO exposures were not linked to pneumonia risk.

Figure. Density Plots of Prenatal and Postnatal Exposures to Fine Particulate Matter With a Diameter of Less Than or Equal to 2.5 µm (PM2.5) by Infant-Quarter and Severe Pneumonia Status During Infancy.

In a complementary intention-to-treat analysis, high adherence to LPG stove use substantially reduced infant PM2.5 exposure median levels (24.2 µg/m³ in LPG group versus 66.0 µg/m³ in biomass group) but did not significantly reduce severe pneumonia incidence (incidence rate ratio 0.96; 98.75% CI, 0.64–1.44; P = 0.81) (McCracken et al., 2024, NEJM). These findings challenge prior assumptions of the magnitude of pneumonia risk attributable to HAP from biomass cooking.

Evidence from Observational and Cluster-Randomized Studies: Ghanaian Context

Earlier findings from the Ghana Randomized Air Pollution and Health Study (GRAPHS) presented some conflicting evidence. This cluster-randomized trial enrolled 1414 pregnant women and measured personal CO exposure repeatedly before and after birth (Adetona et al., 2021, Chest). The study reported a modest positive association between prenatal CO exposure and the risk of both pneumonia (RR 1.10 per ppm increase) and severe pneumonia (RR 1.15), with suggestive sex-specific vulnerabilities particularly among female infants.

However, another Ghanaian cluster RCT evaluating improved biomass cookstoves and LPG interventions found no significant reductions in physician-diagnosed severe pneumonia or improvement in birth weight (Clark et al., 2021, BMJ Glob Health). This lack of efficacy was potentially related to insufficient pollution reduction, as exposures in intervention groups remained above WHO targets.

Mechanistic Insights: Prenatal HAP Exposure and Infant Lung Function

Prenatal HAP exposure may impair infant lung development and function, potentially increasing susceptibility to pneumonia. Data from GRAPHS showed that elevated prenatal CO exposure correlated with altered infant lung function parameters at 30 days, including increased respiratory rate and reduced respiratory compliance (McCracken et al., 2019, Am J Respir Crit Care Med). Such physiological disruptions could mechanistically enhance pneumonia risk.

These findings offer a biological basis for observed sex-specific effects and underscore the importance of timing and intensity of exposure in respiratory health outcomes.

Expert Commentary

The convergence of data from multinational RCTs and observational cohorts offers a nuanced perspective on the relationship between biomass-related HAP and severe infant pneumonia. The recently published HAPIN trial’s robust design, including extensive personal exposure monitoring and rigorous clinical endpoint verification, renders its negative findings particularly compelling, suggesting previous observational associations may have been confounded or mediated by factors beyond PM2.5 and CO exposure alone.

However, potential limitations include residual confounding by unmeasured indoor air pollutants or environmental tobacco smoke, exposure misclassification despite sophisticated monitoring, and variations in host susceptibility and exposure patterns. Additionally, the degree of exposure reduction achieved in some interventions might not have sufficed to demonstrate clinical benefits.

Mechanistic evidence supports that prenatal exposure can disrupt lung development, which aligns with observed epidemiological patterns, particularly in female infants. This sexually dimorphic vulnerability invites further investigation into molecular and immunological pathways influenced by HAP.

Clinically, these findings warrant cautious interpretation. While promoting clean cooking technologies remains critical for multiple health and environmental reasons, expectations regarding pneumonia risk reduction may need recalibration. Greater focus on holistic environmental control, nutritional interventions, and vaccination strategies might yield more tangible benefits in pneumonia morbidity and mortality.

Conclusion

Emerging high-quality evidence challenges the longstanding paradigm that PM2.5 and CO exposures from biomass cooking are major independent drivers of severe pneumonia in infancy. Despite substantial pollution reduction through LPG interventions, randomized data reveal no significant decline in pneumonia incidence, contrasting with some earlier observational and mechanistic studies.

Future research should aim to:

- Elucidate complex pathways linking prenatal and postnatal HAP exposure with lung development, immune function, and infection susceptibility.

- Develop and validate more comprehensive exposure metrics encompassing multiple pollutants and contextual factors.

- Investigate sex-specific physiological responses and long-term respiratory health trajectories.

- Integrate intervention trials with socio-behavioral, nutritional, and vaccination strategies for multifactorial pneumonia prevention.

In sum, current data necessitate a paradigm shift toward a multifaceted approach to infant pneumonia prevention that transcends sole reliance on reductions in biomass-related indoor air pollution.

References

- McCracken JP, McCollum ED, Steenland K, et al.; Household Air Pollution Intervention Network (HAPIN) Investigators. Exposure to Household Air Pollution From Biomass Cooking and Severe Pneumonia in Infants. JAMA Netw Open. 2025;8(10):e2538721. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2025.38721 IF: 9.7 Q1 .

- McCracken JP, McCollum ED, Clasen T, et al. Liquefied Petroleum Gas or Biomass Cooking and Severe Infant Pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 2024;390(1):32-43. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2305681 IF: 78.5 Q1 .

- Adetona O, et al. Prenatal and Postnatal Household Air Pollution Exposures and Pneumonia Risk: Evidence From the Ghana Randomized Air Pollution and Health Study. Chest. 2021;160(5):1634-1644. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2021.06.080 IF: 8.6 Q1 .

- Clark ML, et al. A cluster randomised trial of cookstove interventions to improve infant health in Ghana. BMJ Glob Health. 2021;6(8):e005599. doi:10.1136/bmjgh-2021-005599 .

- McCracken JP, et al. Prenatal Household Air Pollution Is Associated with Impaired Infant Lung Function with Sex-Specific Effects. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;199(6):738-746. doi:10.1164/rccm.201804-0694OC .