Highlights

– A 2013 histopathologic reclassification of neuroendocrine neoplasms (NENs) largely explains an artifactual rise in colorectal cancer incidence among people aged 15–39 years in a French registry cohort (Jooste et al., JAMA Netw Open 2025).

– Large multicohort genomic analysis (Li et al., Lancet Oncol 2025) identifies divergent mutational landscapes in hypermutated versus non‑hypermutated EOCRC, including enrichment of APC, KRAS, CTNNB1 in hypermutated EOCRC and higher TMB in hypermutated younger patients.

– Population‑specific pathway differences (Monge et al., Cancers 2025) and higher MSI‑high and PD‑L1 prevalence in EOCRC (Tang et al., Int J Surg 2024) underscore biological heterogeneity with potential therapeutic implications.

Background — clinical context and unmet needs

Early‑onset colorectal cancer (EOCRC), commonly defined as colorectal cancer (CRC) diagnosed before age 50, has attracted intense clinical and research attention because of rising incidence in many regions and diagnostic, therapeutic, and public health implications. Clinicians and policy-makers need to distinguish true epidemiologic increases from artifactual changes due to classification or coding, and to characterise biologically meaningful molecular subtypes that may inform screening, prognostication, and targeted or immunotherapeutic strategies.

Study designs and data sources synthesised

This integrated appraisal synthesises four recent papers with complementary scope:

- Jooste et al. (JAMA Netw Open 2025): a population‑based cohort (FRANCIM) covering 2004–2021 (n=63,780 CRC cases) comparing age‑specific incidence trends for adenocarcinoma (ADC) and neuroendocrine neoplasms (NENs) and tumor extension at diagnosis.

- Li et al. (Lancet Oncology 2025): an international, multicohort genomic analysis of 17,133 CRC tumour samples from seven cohorts, stratifying tumours into hypermutated (TMB>15 muts/Mb) and non‑hypermutated and comparing mutation frequencies between EOCRC and LOCRC.

- Monge et al. (Cancers 2025): pathway‑focused bioinformatics analysis of 3,412 patients comparing WNT, TGF‑β, and RTK/RAS pathway alterations across EOCRC vs LOCRC and between Hispanic/Latino (H/L) and non‑Hispanic white (NHW) groups.

- Tang et al. (Int J Surg 2024): a case‑controlled NGS study of 11,344 CRC patients assessing TMB, MSI, PD‑L1, and mutation patterns in EOCRC vs LOCRC.

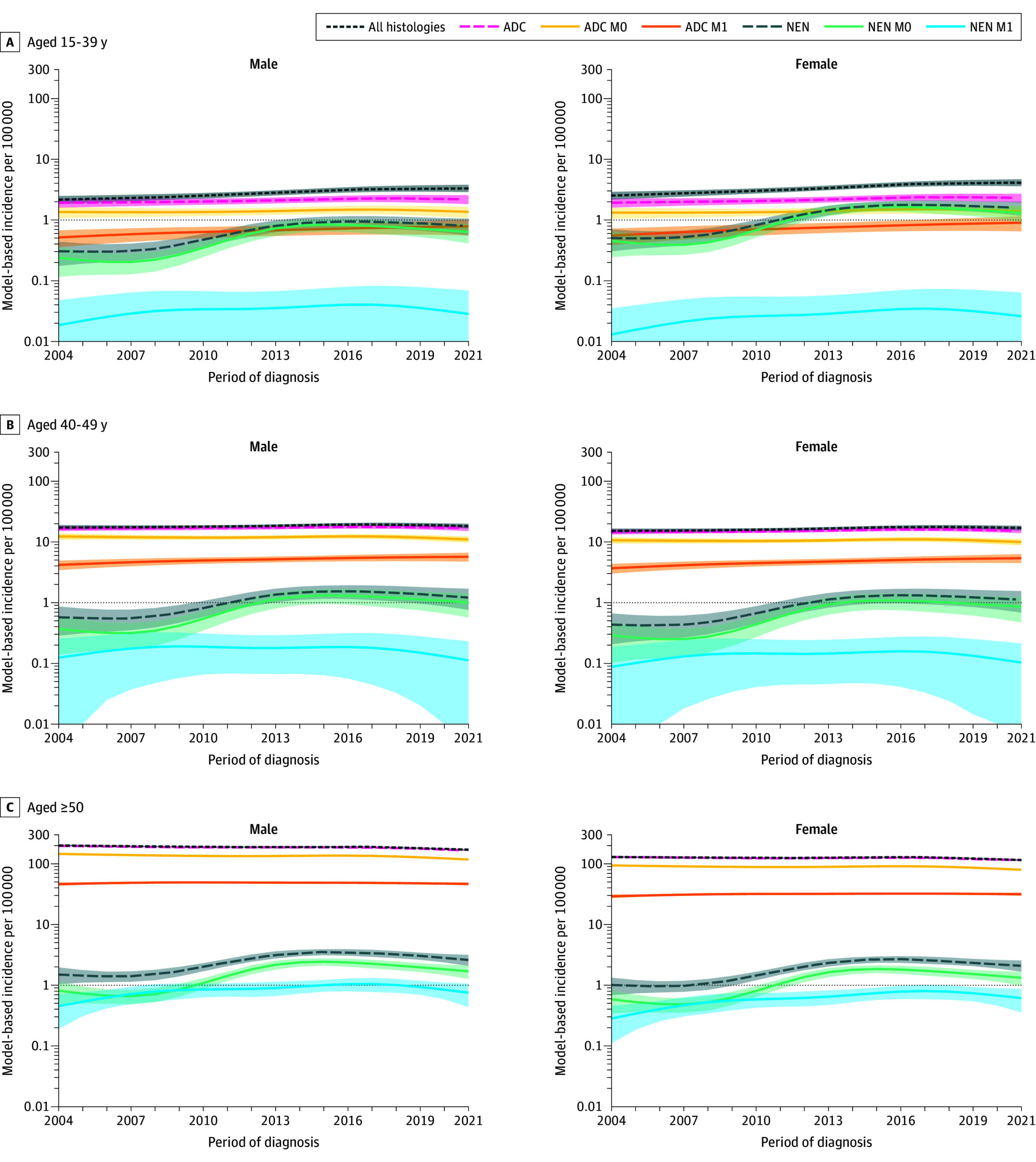

Key findings — epidemiology: an artifactual signal driven by NEN reclassification

Jooste et al. document an apparent increase in CRC incidence among those aged 15–39 years (APC 2.6–2.9% per year) but not in 40–49-year-olds. Crucially, ADC rates were stable across ages while NEN rates rose sharply between 2004 and 2013 (annual increases 10–13%) and then declined after 2013. The 2013 change in NEN classification therefore explains much of the apparent EOCRC rise in the youngest age stratum: 29.7% of CRC in 15–39-year-olds were NENs versus 5.7% in 40–49 and 1.4% in ≥50-year-olds. Public‑health inference: at least part of the observed EOCRC ‘‘epidemic’’ in very young adults reflects diagnostic/classification artefact, not a sudden surge in adenocarcinoma incidence. Importantly, Jooste et al. still documented a true increase in ADC with distant metastasis (M1) within EOCRC over the full period, indicating concurrent real clinical concerns.

Figure 2. Model-Based Specific Incidence of Colorectal Cancer by Histopathological Type, Tumor Extension, Sex, and Age Class.

Key findings — molecular taxonomy: hypermutated versus non‑hypermutated EOCRC

Li et al.’s large genomic consortium provides the most comprehensive mutational map. Their principal observations:

- Hypermutated group: EOCRC tumours had higher TMB than older counterparts (mean ratio 1.11). EOCRC hypermutated tumours were enriched for APC, KRAS, CTNNB1 and TCF7L2 mutations and depleted for BRAF and RNF43 mutations relative to LOCRC. This suggests a unique constellation of WNT/β‑catenin and RAS‑pathway alterations within hypermutated EOCRC.

- Non‑hypermutated group: EOCRC tumours had lower TMB than LOCRC. TP53 mutations were more common in EOCRC here, whereas several canonical driver mutations (e.g., BRAF, KRAS) were less frequent than in older patients.

- Interpretation: EOCRC is molecularly heterogeneous; hypermutated EOCRC shows an unexpectedly high mutation accumulation and specific pathway enrichments that may contribute to early carcinogenesis and could be targetable or prognostically informative.

Key findings — MSI, TMB, PD‑L1 and clinical presentation

Tang et al. add clinically actionable detail: EOCRC patients had a higher prevalence of MSI‑high (MSI‑H) tumours (10.2% vs 2.2% in LOCRC), higher overall TMB (especially in MSI‑H tumours), and higher PD‑L1 expression. Within EOCRC, MSI‑H tumours presented with earlier TNM stage but poorer differentiation and more mucinous histology. Several genes (FBXW7, FAT1, ATM, ARID1A, KMT2B) were enriched among EOCRC MSI‑H tumours, suggesting molecular patterns that intersect with immune responsiveness. Clinically, MSI‑H and high TMB/PD‑L1 point to potential eligibility for immune checkpoint inhibitors in a subset of younger patients.

Key findings — pathway and population heterogeneity

Monge et al. emphasise ethnic and pathway‑level heterogeneity. Among Hispanic/Latino patients, EOCRC demonstrated lower RTK/RAS alteration frequency than LOCRC but higher prevalence of specific alterations (CBL, NF1) and distinct increases in RNF43 (WNT) and BMPR1A (TGF‑β). Differences between H/L and NHW EOCRC cases (e.g., RNF43, BMPR1A, MAPK3) suggest ancestry‑associated genomic patterns that may influence tumour behavior and response to pathway‑specific agents. Interestingly, in NHW EOCRC WNT pathway alterations correlated with improved survival; this relationship was not observed in H/L patients, indicating population‑specific prognostic associations.

Expert commentary — interpreting concordance and discordance across studies

Taken together, these studies define a nuanced picture: some of the epidemiologic alarm about EOCRC, particularly in very young adults, reflects diagnostic reclassification of NENs rather than a new surge in adenocarcinoma; concurrently, independent genomic datasets demonstrate biologically distinct EOCRC subtypes with potential clinical relevance. Strengths include population‑level incidence data and large, multinational genomic sampling. Limitations include heterogeneity of sequencing platforms, cohort ascertainment bias (tertiary centres vs population registries), and under‑representation of some racial/ethnic groups. Linkage between registry incidence and matched molecular data remains incomplete, limiting direct epidemiologic‑molecular correlation. Clinicians should therefore interpret incidence trends alongside diagnostic practices and should not assume uniform biology across all EOCRC cases.

Clinical and translational implications

1) Epidemiology and public health: Registries and surveillance programs must account for classification changes — coding stratification by histology (ADC vs NEN) and clear annotation of classification versions are essential to avoid misinterpretation of secular trends.

2) Diagnostic workup of young CRC patients: Routine testing for MSI status, comprehensive targeted NGS panels that capture WNT/β‑catenin, RAS/MAPK, TGF‑β and DNA‑repair pathway genes, and quantification of TMB/PD‑L1 should be standard in EOCRC to identify actionable targets and immunotherapy candidates.

3) Therapeutic selection: Higher MSI‑H/TMB and PD‑L1 in EOCRC subsets support immunotherapy consideration; pathway alterations (e.g., KRAS, BRAF, RNF43, APC) will influence use of targeted agents and enrolment in precision trials. Population‑specific differences argue for inclusive trial enrollment and subgroup analyses by ancestry.

Roadmap and outlook — towards a practical molecular taxonomy for EOCRC

To move from descriptive genomics to a clinically actionable molecular classification, I propose a pragmatic, nested taxonomy integrating histology, global mutation burden, key pathway alterations, and immunogenic markers:

- Step 1 (histology): Separate ADC from NEN and other histotypes using contemporary WHO criteria and document classification year/version.

- Step 2 (hypermutation axis): Classify tumours as hypermutated (e.g., TMB>15 muts/Mb or MSI‑H/POLE‑mutant) versus non‑hypermutated.

- Step 3 (pathway module): Within each axis, report dominant pathway alterations — WNT (APC, CTNNB1, RNF43), RAS/MAPK (KRAS, NRAS, BRAF, NF1, CBL), TGF‑β/BMP (BMPR1A), DNA‑repair (MMR genes, POLE) — and TP53/PI3K status.

- Step 4 (immune module): Provide MSI status, TMB, and PD‑L1 expression to inform immunotherapy eligibility.

Operationalizing this taxonomy requires harmonized panels, consensus thresholds for TMB/MSI, standardized PD‑L1 assays, and integration of ancestry/epidemiologic metadata. Prospective registries linking molecular data to clinical outcomes in diverse populations are a priority.

Research priorities

– Prospective population‑based cohorts that combine registry incidence with systematic molecular profiling to disentangle true incidence shifts from diagnostic artifacts.

– Mechanistic studies of hypermutated EOCRC: Why do younger hypermutated tumours accumulate specific mutational signatures? Role of germline predisposition, environmental exposures, microbiome, and defective DNA‑repair should be interrogated.

– Inclusion of underrepresented populations in sequencing studies and clinical trials to validate ancestry‑specific associations and ensure equitable therapeutic development.

– Clinical trials stratified by the proposed taxonomy to test pathway‑directed therapies and immunotherapy in EOCRC‑specific contexts.

Conclusions

Recent work reconciles two seemingly discordant observations about EOCRC: part of the apparent epidemiologic rise in very young adults is attributable to a 2013 NEN classification change, but independent genomic analyses reveal true biological heterogeneity and clinically relevant molecular subtypes among EOCRC adenocarcinomas. The clinical imperative is twofold: epidemiologists must adjust incidence analyses for classification artefacts, and clinicians should adopt systematic molecular profiling in younger patients to guide precision therapy. A harmonized, clinically oriented molecular taxonomy — integrating histology, hypermutation status, pathway alterations, and immune biomarkers — will improve prognostication, inform targeted treatment decisions, and direct future preventive strategies.

References

Jooste V, Nousbaum JB, Alves A, et al. Epidemiological Classification Changes and Incidence of Early‑Onset Colorectal Cancer. JAMA Netw Open. 2025;8(11):e2541732.

Li J, Pan Y, Guo F, et al. Patterns in genomic mutations among patients with early‑onset colorectal cancer: an international, multicohort, observational study. Lancet Oncol. 2025;26(8):1055‑1066.

Monge C, Waldrup B, Carranza FG, Velazquez‑Villarreal E. Molecular Heterogeneity in Early‑Onset Colorectal Cancer: Pathway‑Specific Insights in High‑Risk Populations. Cancers (Basel). 2025;17(8):1325.

Tang J, Peng W, Tian C, et al. Molecular characteristics of early‑onset compared with late‑onset colorectal cancer: a case controlled study. Int J Surg. 2024;110(8):4559‑4570.