Highlight

– Cyclic Cushing’s syndrome (cCS) is frequently misdiagnosed or delayed even at tertiary centres: 41% experienced delayed diagnosis and 43% delayed therapy.

– In 110 patients, biochemical cyclicity showed median urinary free cortisol (UFC) peaks 7.4× upper limit of normal (ULN) and troughs 0.31×ULN; ectopic cCS produced the most frequent and pronounced peaks.

– Imaging missed tumours in 32% and 8% underwent unwarranted surgery at the wrong site; bilateral inferior petrosal sinus sampling (BIPSS) performed during troughs contributed to misclassification.

– Practical steps include repeated home salivary cortisol collection, confirming biochemical hypercortisolism before BIPSS, planning BIPSS/imaging during active peaks, and routine provision of emergency glucocorticoids for patients at risk of spontaneous adrenal insufficiency.

Background

Cushing’s syndrome (CS) is the clinical state resulting from chronic glucocorticoid excess and is associated with significant morbidity and mortality if untreated. Cyclic Cushing’s syndrome (cCS) is a biologically and clinically challenging variant characterised by alternating periods of hypercortisolaemia (peaks) and eucortisolaemia or hypocortisolaemia (troughs). Cycles may be days to months long and often irregular, producing intermittently clear clinical and biochemical abnormalities that complicate diagnosis, localisation, and management. Traditional pathways for diagnosing and subtyping CS assume a persistent biochemical excess; they are therefore vulnerable to failure when applied during troughs of cCS. The international retrospective cohort reported by Nowak et al. (Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2025) addresses these diagnostic and outcome gaps by assembling 110 well-characterised cCS cases from 43 endocrine centres worldwide.

Study design

This was a retrospective, multicentre observational cohort capturing patients with confirmed CS who demonstrated at least two hypercortisolaemic peaks and at least one spontaneous eucortisolaemic or hypocortisolaemic trough. Data were collated from 43 specialised endocrine centres across 21 countries between Dec 1, 2023 and Feb 2, 2025. Clinical, biochemical, imaging, invasive testing (including BIPSS), treatments, complications (including spontaneous adrenal insufficiency), and outcomes were recorded. Cyclicity assessment primarily relied on serial 24 h urinary free cortisol (UFC) measurements, with complementary use of late-night salivary cortisol and plasma cortisol where available. The cohort included pituitary, ectopic, adrenal and occult cCS subtypes, and follow-up median was 5.8 years (IQR 2.6–10.5).

Key findings

Cohort characteristics

110 patients met inclusion criteria. Median age at diagnosis was 44.0 years (IQR 31.8–58.3); 76% were female (84/110). cCS aetiologies were pituitary in 64% (70/110), ectopic in 23% (25/110), adrenal in 3% (3/110), and occult in 11% (12/110).

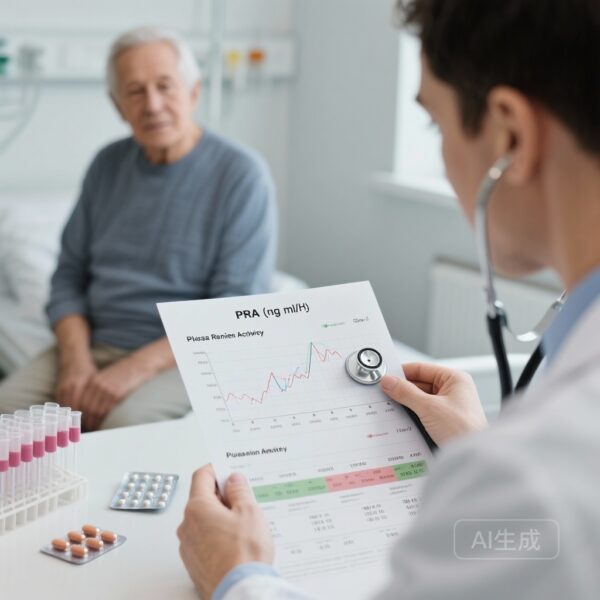

Biochemical cycle patterns

Serial 24 h UFC was the predominant method to define cyclicity. Median peak UFC was 7.40 × ULN (range 0.44–299); median trough UFC was 0.31 × ULN (range 0.02–0.98). The median number of documented peaks was 3.0 (IQR 2.0–4.0). Among patients with detailed temporal data, cycles occurred at irregular intervals in 86% (55/64). Ectopic cCS demonstrated the most frequent and pronounced peaks consistent with abrupt or high-amplitude hypercortisolism arising from non-pituitary ACTH sources.

Clinical manifestations and complications

Symptoms and signs of cortisol excess worsened during peaks for 81% (87/108) and improved during troughs for 74% (79/107), illustrating the dynamic clinical course. Notably, 28% (31/110) experienced spontaneous adrenal insufficiency at least once, likely reflecting oversuppression of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis during troughs and/or post‑surgical or medical therapy effects.

Diagnostic and management pitfalls

Imaging failed to detect tumours in 32% (35/110), and 8% (9/110) underwent unwarranted surgery at incorrect anatomical sites due to misclassification. BIPSS — a gold standard for distinguishing pituitary from ectopic ACTH sources — was performed during biochemical troughs in 14 patients (18% of BIPSS procedures), contributing to incorrect lateralisation or false negatives. Delayed diagnosis occurred in 41% (45/110) and delayed therapy in 43% (47/110), highlighting system and disease-driven impediments to care. Mortality during observation was 3% (3/110).

Treatment outcomes

After median 5.8 years follow-up, 50% (55/110) achieved complete biochemical surgical remission, 6% (7/110) experienced spontaneous remission, 20% (22/110) were medically controlled, 5% (6/110) had partial remission, 10% (11/110) remained uncontrolled, and 8% (9/110) were lost to follow-up. Outcomes varied by aetiology and by timeliness of diagnosis and therapy.

Clinical implications and practical recommendations

The Nowak et al. cohort provides actionable lessons for clinicians evaluating suspected CS and managing confirmed cCS.

1) Expect and test for cyclicity — build a sample series

Because single-point testing risks false negatives during troughs, clinicians should obtain serial biochemical measurements when cCS is suspected. Repeated late-night salivary cortisol, serial 24 h UFC and overnight dexamethasone suppression tests across weeks to months increase sensitivity. Home collection kits for late-night salivary cortisol should be offered and patients instructed in timing and collection to capture peaks. Documenting a pattern — rather than a single abnormal value — supports diagnosis and avoids missteps.

2) Time invasive localisation to biochemical peaks

BIPSS and targeted imaging should be scheduled when biochemical hypercortisolism is demonstrably present. Performing BIPSS during biochemical troughs risks false-negative central-to-peripheral ACTH gradients and misclassification that may prompt wrong-site surgery. Practically, confirm hypercortisolism (eg, elevated UFC or salivary cortisol consistent with a peak) within days of planned BIPSS.

3) Interpret imaging with cyclicity in mind

Negative or equivocal imaging is common. For occult ACTH sources or imaging-missed lesions, repeat imaging timed to biochemical peaks, dedicated thin‑slice pituitary MRI protocols, and whole-body cross-sectional or functional imaging (for ectopic sources) should be considered. Multidisciplinary review (endocrinology, neuroradiology, endocrinosurgery, nuclear medicine) is recommended.

4) Prepare for adrenal insufficiency and provide safety planning

Given that nearly one-third of patients had spontaneous adrenal insufficiency, clinicians should counsel patients on adrenal crisis signs, provide an emergency steroid plan, and consider prescribing a hydrocortisone emergency kit. Patients should be advised to carry steroid alert information and trained on when to escalate care.

5) Avoid premature surgery

Given the risk of unwarranted operations reported, surgical decisions should be based on concordant biochemical, imaging and/or invasive testing performed under conditions of biochemical activity, and ideally within a multidisciplinary team context. When diagnostic uncertainty persists, consider watchful waiting with serial testing rather than immediate, irreversible surgery.

Expert commentary and context

Guidelines for diagnosing Cushing’s syndrome emphasise multiple, convergent biochemical assessments to establish hypercortisolism before localisation attempts (Nieman et al., Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline, 2008). The Nowak et al. cohort reinforces and extends these principles to cCS: the intermittent nature of cCS magnifies the pitfalls when single tests guide major diagnostic or therapeutic steps. Although the cohort is enriched by referral to specialised centres (referral bias), it demonstrates that even expert teams encounter diagnostic delay, incorrect localisation and high complication rates when cyclicity is not explicitly addressed.

Limitations

The study’s retrospective design predisposes to selection and information biases. Case ascertainment occurred at specialized centres, which may select for more complicated or refractory cases and may not reflect community practice. Assay heterogeneity across centres and inconsistent definitions of ULN may introduce variability in reported multipliers of ULN. Finally, documentation of cycles depends on the density and quality of serial testing; under‑ or over‑estimation of cycle frequency is possible.

Conclusion

Cyclic Cushing’s syndrome presents unique diagnostic and management challenges. The international cohort of 110 patients underscores the frequency of diagnostic delays, imaging misses, inappropriate surgeries and spontaneous adrenal insufficiency. Practical measures—serial biochemical testing (including home late‑night salivary cortisol kits), confirming hypercortisolism before BIPSS or localisation procedures, multidisciplinary review of imaging, and proactive adrenal insufficiency safety planning—can reduce avoidable harm and improve outcomes. Prospective, standardized pathways and accessible home-testing protocols merit development and evaluation to optimise care in this high-risk syndrome.

Funding and trial registration

Funding: none declared in the primary report. No clinicaltrials.gov registration applies for this retrospective cohort.

References

1) Nowak E, Zhang Q, Zhang S, et al. Cycle characterisation and clinical complications in patients with cyclic Cushing’s syndrome: insights from an international retrospective cohort study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2025;13(12):1030-1040. doi:10.1016/S2213-8587(25)00249-9.

2) Nieman LK, Biller BMK, Findling JW, et al. The diagnosis of Cushing’s syndrome: an Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93(5):1526-1540. doi:10.1210/jc.2008-0125.

Thumbnail image prompt

A worried middle-aged woman sitting in a bright clinic room, holding a saliva collection tube and instruction leaflet; in the background, faint overlays of pituitary MRI and adrenal CT scans and a printed 24 h urinary free cortisol graph, realistic photographic style, soft clinical lighting.