Highlights

Research indicates that Black patients undergo benign hysterectomy with a significantly higher risk of major postoperative complications compared to White patients, a disparity that remains even after adjusting for medical comorbidities and uterine weight.

Key modifiable risk factors associated with increased complications include longer operative times, the use of laparotomy over minimally invasive techniques, non-standard preoperative antibiotic regimens, and treatment by low-volume surgeons.

Black patients were 39% more likely to experience major complications than White patients after adjusting for non-modifiable risk factors, highlighting a critical need for systemic changes in surgical delivery.

Standardizing perioperative protocols and improving access to high-volume surgeons are identified as essential strategies to close the racial gap in gynecologic surgical outcomes.

Background: The Unmet Need for Surgical Equity

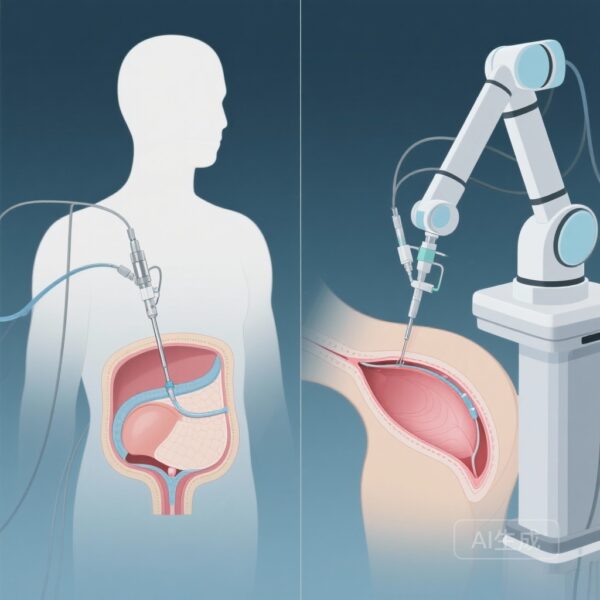

Hysterectomy is one of the most common surgical procedures performed on women globally. While the transition toward minimally invasive surgery (MIS) has improved outcomes generally, the benefits of these advancements have not been shared equally across racial groups. Historically, clinical data has consistently shown that Black patients experience higher rates of perioperative complications, regardless of whether the procedure is performed via an abdominal, laparoscopic, or robotic route.

The standard clinical explanation for these disparities often focuses on patient-level factors, such as higher rates of uterine fibroids, larger uterine weights, and a higher prevalence of medical comorbidities like hypertension or diabetes. However, even when these variables are meticulously controlled for, the disparity persists. This suggests that the root of the problem may lie not within the patients themselves, but within the systems of care and the surgical practices applied to them. There is a critical unmet need to identify factors that are within the control of surgeons and hospital systems—potentially modifiable factors—that can be targeted to ensure equitable healthcare delivery.

Study Design: A Deep Dive into the MSQC Database

To address this gap, researchers conducted a retrospective cohort study utilizing data from the Michigan Surgical Quality Collaborative (MSQC) database. The MSQC is a multi-institutional consortium that collects high-fidelity, clinical data on surgical outcomes across the state of Michigan. The study population included 18,395 patients who underwent hysterectomy for benign, non-obstetrical indications between January 2015 and December 2018. Of these, 82.4% (n=15,164) identified as White and 17.6% (n=3,231) identified as Black.

The primary outcome measured was the occurrence of major postoperative complications, which included events such as surgical site infections, venous thromboembolism, unintended return to the operating room, and readmission within 30 days. The researchers evaluated the association between these outcomes and several categories of risk factors: patient-level factors (age, BMI, comorbidities), perioperative clinical practices (antibiotic choice, hemostatic agents), surgical/intraoperative factors (operative time, surgical approach), and hospital/surgeon characteristics (surgeon volume).

Key Findings: Quantifying the Disparity

The overall rate of major postoperative complications in the cohort was 1.6%. However, a stark contrast emerged when the data was disaggregated by race. Black patients experienced major complications at a rate of 2.8%, compared to 1.4% in White patients (P<.001). This signifies that Black patients faced double the raw risk of major complications.

After performing a multivariable logistic regression to adjust for non-modifiable patient factors—including insurance type, BMI, preoperative anemia, diabetes, and uterine weight—Black race remained an independent predictor of major postoperative complications. The adjusted odds ratio (aOR) was 1.39 (95% CI, 1.04-1.85; P=.026). This finding reinforces the hypothesis that patient health status alone does not account for the observed inequities.

Identifying the Modifiable Culprits

The core contribution of this study is the identification of five specific factors that are potentially modifiable by the clinician or the institution. These factors were found to be independently associated with a higher risk of major complications:

1. Operative Time: Longer surgeries were associated with increased risk (aOR 1.13 per hour; 95% CI, 1.01-1.25). Black patients frequently experience longer operative times, often due to complex pathology, yet this factor contributes significantly to morbidity across the board.

2. Surgical Approach: The use of laparotomy (open surgery) instead of a minimally invasive approach was a significant risk factor (aOR 1.39; 95% CI, 1.03-1.84). Black patients are historically more likely to be offered open surgery, even when MIS is clinically feasible.

3. Hemostatic Agents: The use of topical hemostatic agents was unexpectedly associated with higher complication rates (aOR 1.55; 95% CI, 1.22-1.96). This may serve as a proxy for intraoperative difficulty or represent a practice pattern that warrants further investigation.

4. Preoperative Antibiotics: The use of a non-preferred or non-standard preoperative antibiotic regimen significantly increased the risk of complications (aOR 1.50; 95% CI, 1.15-1.94). Adherence to evidence-based prophylaxis is a clear target for hospital-level quality improvement.

5. Surgeon Volume: Patients operated on by surgeons in the lowest volume tertile had a higher risk of complications (aOR 1.45; 95% CI, 1.00-2.04). Black patients are disproportionately treated by lower-volume surgeons, suggesting a disparity in access to specialized expertise.

Expert Commentary: Moving from Observation to Intervention

The findings of this study provide a roadmap for health systems aiming to achieve surgical equity. For decades, the medical community has observed racial disparities in surgery, often attributing them to the biological or socioeconomic characteristics of the patients. This research shifts the focus toward the “provider side” of the equation. If the disparity is driven by surgical approach, antibiotic choice, and surgeon volume, then the solution is structural, not biological.

From a clinical perspective, the association between laparotomy and poor outcomes is well-documented. However, the fact that Black patients are less likely to receive MIS suggests a bias in surgical counseling or a lack of MIS training among surgeons who predominantly serve Black communities. Similarly, the finding regarding non-preferred antibiotics highlights a failure in standardized care delivery. Standardizing the perioperative pathway—ensuring every patient receives the evidence-based antibiotic and the least invasive approach possible—is a tangible step toward equity.

Furthermore, the data regarding surgeon volume points toward a systemic referral issue. If Black patients are not being referred to high-volume centers or high-volume specialists, they are being denied the “volume-outcome” benefit that is a hallmark of modern surgical quality. Health policy experts must look at how insurance networks and hospital locations influence these referral patterns.

Conclusion: Toward a More Equitable Standard of Care

In summary, while racial disparities in benign hysterectomy are persistent and complex, this study identifies actionable targets for improvement. To reduce the 39% higher risk of complications faced by Black patients, clinical teams must prioritize the use of minimally invasive surgical approaches, strictly adhere to preferred antibiotic prophylaxis regimens, and work to minimize operative times through surgical efficiency and standardized techniques.

Crucially, hospitals must ensure that Black patients have equal access to high-volume, specialized surgeons. While modifying these clinical factors may not eliminate the disparity entirely—given the systemic nature of racism in healthcare—it provides a clear evidence-based framework for immediate quality improvement. Future research should continue to explore the nuances of intraoperative decision-making and the socio-structural barriers that prevent Black patients from receiving optimal surgical care.

References

Richardson D, Lim CS, Liu Y, Morgan DM, As-Sanie S, Santiago S, Hong CX, Till SR. Identifying potentially modifiable risk factors associated with racially disparate postoperative outcomes following benign hysterectomy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2025 Dec 2:S0002-9378(25)00872-5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2025.11.036. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 41344529.