The Evolution of Parkinson’s Management

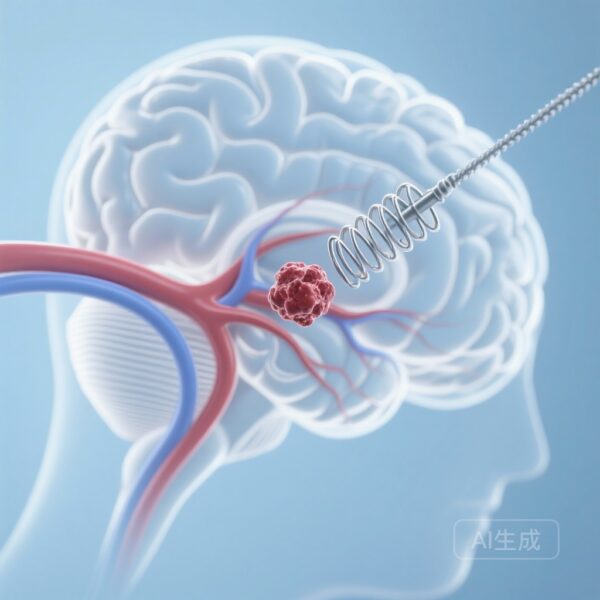

For decades, Parkinson’s disease (PD) has been managed through a combination of medication and, for many, Deep Brain Stimulation (DBS). Traditional DBS, often referred to as continuous DBS (cDBS), operates much like a cardiac pacemaker. It delivers a constant, steady stream of electrical pulses to specific regions of the brain, such as the subthalamic nucleus, to suppress motor symptoms like tremors, rigidity, and bradykinesia (slowness of movement). While life-changing for many, this ‘always-on’ approach has a significant limitation: the brain’s needs are not constant.

Throughout the day, a person with Parkinson’s experiences fluctuating levels of dopamine and varying degrees of physical activity. A fixed level of stimulation that works while a patient is walking may be too high while they are resting, leading to side effects like dyskinesia (involuntary, jerky movements). Conversely, it might be too low during periods of high stress or movement, leading to ‘off’ periods where symptoms return. This is the challenge that adaptive deep brain stimulation (aDBS) aims to solve.

The Case of Robert: The Need for Precision

To understand the impact of this technology, consider Robert, a 65-year-old retired civil engineer who has lived with Parkinson’s for over a decade. Robert underwent traditional DBS surgery five years ago. While it initially helped him regain control over his tremors, he found himself in a constant tug-of-war. To suppress his rigidity during his morning walks, his doctors set the stimulation level high. However, by mid-afternoon, this same level caused Robert to experience troublesome dyskinesia—uncontrollable swaying and twitching—making it difficult for him to focus on his woodworking hobby. Robert’s experience is common; the fixed nature of traditional DBS often forces a compromise between symptom control and side-effect management.

What is Adaptive Deep Brain Stimulation?

Adaptive DBS is often described as a ‘smart thermostat’ for the brain. Just as a thermostat measures the temperature of a room and turns the heater on or off to maintain a target level, aDBS senses specific neural signals—known as biomarkers—and automatically adjusts the stimulation amplitude in real-time.

The primary biomarker used in aDBS is the ‘beta oscillation.’ In people with Parkinson’s, excessive bursts of beta-band activity in the brain are closely linked to motor symptoms like stiffness and slowness. The aDBS system monitors these beta bursts through the same electrodes used for stimulation. When beta activity rises, indicating a need for more help, the system increases the stimulation. When beta activity falls, the system dials back, saving energy and reducing the risk of stimulation-induced side effects.

The ADAPT-PD Trial: A Pivotal Step Forward

While the concept of closed-loop or adaptive stimulation has existed for years, evidence of its long-term safety and efficacy in real-world, at-home settings has been limited. The ADAPT-PD trial (Long-Term Personalized Adaptive Deep Brain Stimulation in Parkinson Disease) was designed to fill this gap.

This international, nonrandomized clinical trial enrolled 68 participants across the United States, Canada, and Europe between 2020 and 2022. These participants were already stable on traditional cDBS but were transitioned to aDBS to see if the responsive technology could offer superior or equivalent benefits. The study looked at two specific modes of adaptive stimulation: Single Threshold (ST-aDBS) and Dual Threshold (DT-aDBS).

What the Data Tell Us

The results of the trial, published in JAMA Neurology, were highly encouraging. The primary goal was to determine if participants could achieve ‘on-time’ (periods when symptoms are well-controlled) without troublesome dyskinesia, while maintaining safety and tolerability over the long term.

Key Findings from the ADAPT-PD Study:

1. High Success Rate: The primary performance goal was met by 91% of participants in the Dual Threshold (DT-aDBS) group and 79% in the Single Threshold (ST-aDBS) group. This indicates that the vast majority of patients could maintain or improve their symptom control when switching to the smart system.

2. Reduced Energy Consumption: One of the secondary benefits of aDBS is efficiency. In the ST-aDBS mode, there was a 15% reduction in total electrical energy delivered (TEED) compared to traditional continuous DBS. This is significant because lower energy usage can lead to longer battery life for the implanted pulse generator, potentially reducing the frequency of replacement surgeries.

3. Safety and Tolerability: Perhaps most importantly, the long-term use of aDBS (followed for 10 months) was found to be safe. While some stimulation-related adverse events occurred during the initial setup and adjustment phase, nearly all were resolved quickly. There were no serious device-related adverse events during the follow-up period.

4. Improved ‘On-Time’: Exploratory analyses suggested that the Dual Threshold mode, in particular, provided more ‘on-time’ without troublesome dyskinesia compared to the traditional fixed stimulation. This means patients spent more of their day feeling ‘normal’ and less time struggling with either Parkinson’s symptoms or the side effects of the treatment.

Breaking Down the Modes: Single vs. Dual Threshold

The study compared two ways the device ‘decides’ how to adjust stimulation.

In Single Threshold (ST-aDBS), the system has one set point. If the brain’s beta signal goes above that point, the stimulation increases; if it goes below, it decreases. This is a straightforward reactive model.

In Dual Threshold (DT-aDBS), the system uses two points to create a ‘zone’ of desired neural activity. This allows for a more nuanced and gradual adjustment, which may explain why the DT-aDBS group saw slightly higher success rates in the primary endpoint and improved qualitative outcomes in exploratory data.

The Practical Benefits for Patients and Clinicians

For a patient like Robert, aDBS represents a move toward ‘personalized neurology.’ Instead of visiting a clinic every few months for a static adjustment that might be outdated by the time he gets home, his brain is receiving the exact amount of electricity it needs, minute by minute.

For clinicians, the ADAPT-PD trial provides a roadmap for implementing these systems. It demonstrates that while the initial setup (the ‘tuning’ phase) requires careful attention to resolve minor stimulation-related side effects, the long-term payoff is a more stable patient with fewer ‘off’ periods. The reduction in energy use also adds a layer of practical convenience, as patients with non-rechargeable devices will see their implants last longer.

Addressing Common Misconceptions

A common concern among patients regarding new technology is whether the device ‘takes over’ their brain or if they will feel the stimulation changing. In reality, the adjustments are subtle and occur at a sub-perceptual level. The goal of aDBS is not to make the patient feel the electricity, but to make them forget they have a movement disorder altogether. Another misconception is that aDBS replaces medication. While aDBS can significantly reduce the ‘pill burden’ for some, it is currently intended to work in harmony with a patient’s existing pharmacological regimen, providing a more stable baseline that medication alone often cannot achieve.

Expert Insights: The Future of Closed-Loop Systems

Neurologists involved in the study emphasize that this is just the beginning. The ability to sense signals from the brain while simultaneously treating it opens doors for even more sophisticated treatments. Future versions of these devices might incorporate other biomarkers, such as gait sensors or sleep monitors, to further refine the stimulation.

As Dr. Helen Bronte-Stewart and colleagues noted in the study’s conclusion, the tolerability and efficacy of long-term aDBS mark a significant milestone. It proves that the technology is no longer just a laboratory curiosity but a viable clinical tool that can improve the lives of those living with Parkinson’s.

Conclusion

The ADAPT-PD trial confirms that the future of Parkinson’s treatment is responsive, personalized, and data-driven. By moving away from a ‘one-size-fits-all’ electrical dose and toward an adaptive model, medical science is providing patients with the precision they deserve. For Robert and thousands like him, this means more time spent woodworking, walking, and living life, and less time managing the unpredictable fluctuations of a complex disease.

Trial Registration and Funding

Trial Registration: ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT04547712.

The ADAPT-PD study was an international, open-label, prospective trial. Funding for the study and the development of the technology was provided by Medtronic, the manufacturer of the Percept™ PC neurostimulator used in the trial.

References

Bronte-Stewart HM, Beudel M, Ostrem JL, et al. Long-Term Personalized Adaptive Deep Brain Stimulation in Parkinson Disease: A Nonrandomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Neurol. 2025;82(11):1171-1180. doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2025.2781