Highlight

– In a secondary analysis of the PENUT randomized trial, AKI in extremely preterm infants (24–27 weeks’ gestation) was associated with higher adjusted odds of death or moderate to severe neurodevelopmental impairment at 22–26 months’ corrected age (AOR 1.53; 95% CI 1.07–2.18).

– Survivors with AKI had nearly doubled odds of cognitive delay (BSID-III cognitive score <85; AOR 1.94; 95% CI 1.25–2.99).

– Neither AKI stage nor early versus late timing showed an independent association with neurodevelopmental outcomes in adjusted analyses.

Background: Why this question matters

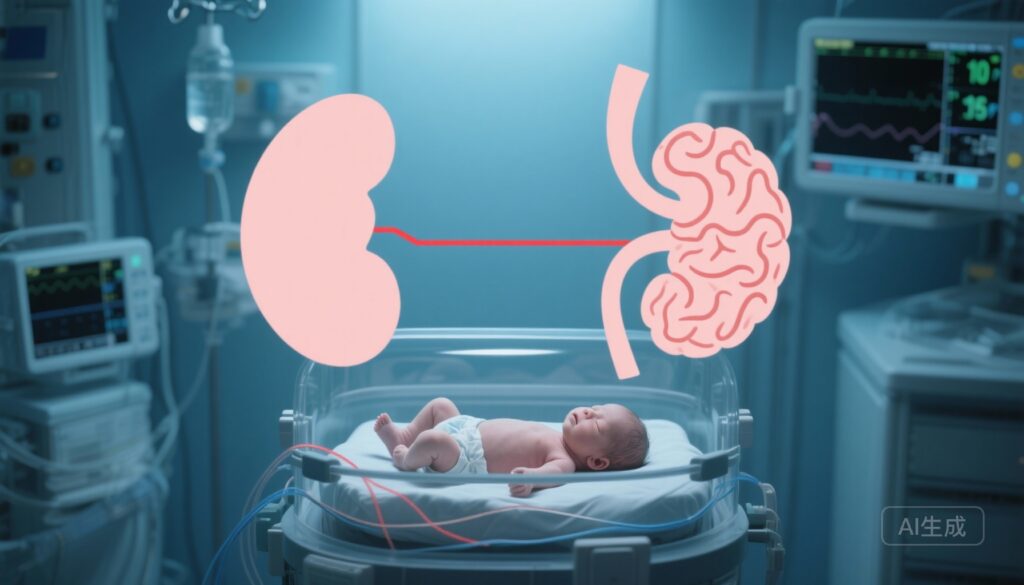

Extremely preterm neonates (born at 24–27 weeks’ gestation) face very high risks of mortality and of long-term neurodevelopmental impairment (NDI), including cognitive and motor deficits and cerebral palsy. Identifying perinatal and neonatal factors that predict or contribute to adverse neurodevelopment is essential for risk stratification, counseling, and targeting preventive strategies.

Acute kidney injury (AKI) is increasingly recognized in neonatal intensive care units (NICUs); it is common among extremely low gestational age neonates because of immature renal physiology, hemodynamic instability, exposure to nephrotoxins, and comorbidities such as sepsis or patent ductus arteriosus. In older children and adults, AKI is associated with increased mortality and longer-term morbidity, including chronic kidney disease and worse functional outcomes. Whether AKI contributes to—or is merely a marker of—adverse neurodevelopment in extremely preterm infants has been less clear.

Study design and population

This is a secondary analysis of data collected in the Preterm Erythropoietin Neuroprotection Trial (PENUT), a randomized, placebo‑controlled phase 3 trial of erythropoietin conducted across 30 US NICUs from December 2013 to September 2016. The trial enrolled infants born at 24 0/7 to 27 6/7 weeks’ gestation. The present analysis considered 660 infants who completed a follow-up visit with a Bayley Scales of Infant Development, Third Edition (BSID-III) performed per protocol between 22 and 26 months’ corrected age.

The primary exposure was AKI during the neonatal period. Analyses evaluated AKI presence, AKI stage, and timing (early: within first 7 days of life; late: after day 7). The primary outcome for this secondary analysis was the composite of death or moderate to severe NDI at 22–26 months’ corrected age. Moderate to severe NDI was defined as moderate to severe cerebral palsy or BSID-III cognitive or motor score <85. Secondary outcomes included the individual components (death, cognitive delay, motor delay, cerebral palsy).

Key findings

Population characteristics

Of the 941 neonates initially enrolled in PENUT, 660 had follow-up BSID-III data available within the prespecified window. Among survivors, 256 (39%) experienced AKI. Infants with AKI were smaller and sicker by several baseline measures: mean gestational age was lower (25.1 ± 1.1 vs 25.7 ± 1.1 weeks), birth weight lower (755 ± 181 g vs 825 ± 189 g), and a higher proportion had a 5‑minute Apgar score <5 (24.1% vs 17.1%). 57% of infants with AKI were male.

Association between AKI and composite outcome

The principal adjusted analysis found that AKI was associated with higher odds of the composite outcome of death or moderate to severe NDI (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] 1.53; 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.07–2.18). This means that, accounting for measured confounders included in the model, infants with AKI had approximately a 50% higher odds of the composite adverse outcome.

Cognitive outcomes

Among the components, the strongest association was with cognitive outcomes: AKI was associated with increased odds of a BSID-III cognitive score <85 (AOR 1.94; 95% CI 1.25–2.99). This represents nearly a doubling of odds for cognitive delay among survivors with AKI compared with those without AKI.

Motor outcomes, cerebral palsy, timing and stage of AKI

The analysis did not find a statistically significant association between AKI and motor scores or the occurrence of moderate to severe cerebral palsy after adjustment, nor did it find differential associations based on AKI stage or whether AKI occurred early versus late in the neonatal course. The absence of associations by stage or timing may reflect limitations in power, misclassification of AKI severity, or complex causal relationships.

Statistical and clinical interpretation

The adjusted models attempted to account for several baseline and illness‑severity variables, but residual confounding is possible. The observed relationship between AKI and worse cognitive outcomes remained after adjustment, strengthening the argument that AKI may be an independent risk factor for adverse neurodevelopment in this population. Nevertheless, causality cannot be established from this observational secondary analysis.

Expert commentary: mechanisms, strengths, and limitations

Biological plausibility and potential mechanisms

Several mechanisms could plausibly link AKI to adverse neurodevelopmental outcomes in preterm infants:

- Systemic inflammation: AKI provokes systemic inflammatory responses and cytokine release, which can disrupt the developing brain and white matter.

- Fluid and hemodynamic instability: AKI often co-occurs with hypo‑ or hypervolemia and blood pressure variability, compromising cerebral perfusion in a vulnerable brain.

- Uremic toxins and metabolic derangements: Accumulation of metabolites might have neurotoxic effects or interfere with neurodevelopmental processes.

- Shared upstream causes: Sepsis, asphyxia, or severe cardiorespiratory illness can concurrently cause AKI and brain injury; in this case AKI may be a marker rather than a mediator.

These plausible pathways strengthen the biological rationale for a link between AKI and neurodevelopmental outcomes, and provide potential targets for intervention.

Strengths of the analysis

- Use of a well-characterized multicenter randomized trial cohort with prospective data collection and a standardized neurodevelopmental follow-up protocol.

- Substantial sample size of extremely preterm infants with granular clinical data allowing adjusted analyses.

- Clinically relevant predefined outcome (death or moderate to severe NDI) assessed at a common developmental time point (22–26 months corrected age).

Limitations and cautions

- Secondary analysis: PENUT was not designed primarily to assess AKI–neurodevelopment relationships; potential for unmeasured confounding remains.

- AKI ascertainment in neonates has intrinsic challenges: neonatal serum creatinine reflects maternal values early after birth and is influenced by low muscle mass and fluid shifts; urine-output–based AKI ascertainment may be inconsistent.

- Missing follow-up: 660 of 941 enrolled infants had BSID-III data in the window—loss to follow-up can bias results if differential by AKI status.

- Heterogeneity of AKI: No observed association with AKI stage or timing could reflect misclassification, limited power, or that the mere presence of AKI identifies infants at higher risk regardless of stage measured by creatinine criteria.

- Outcome measurement: BSID-III at 2 years predicts later function imperfectly; some cognitive or behavioral problems may emerge later in childhood.

Clinical and research implications

For clinicians caring for extremely preterm infants, these findings provide additional impetus to:

- Recognize AKI as a potential marker of increased neurodevelopmental risk and incorporate kidney injury history into counseling and follow-up planning.

- Adopt kidney-protective strategies where possible: minimize exposure to nephrotoxins, optimize fluid and hemodynamic management, and involve neonatal nephrology early when AKI occurs.

- Ensure structured neurodevelopmental surveillance for infants who experience AKI, with timely involvement of early intervention services.

For researchers, priorities include:

- Prospective cohort and mechanistic studies to disentangle whether AKI is a causal contributor to brain injury or an illness‑severity marker.

- Development and validation of neonatal AKI biomarkers that better capture renal injury than creatinine alone in the preterm population.

- Interventional trials testing kidney‑protective approaches and assessing downstream neurodevelopmental outcomes.

Conclusion

This robust secondary analysis of the PENUT trial demonstrates that AKI in extremely preterm infants is associated with higher adjusted odds of the composite outcome of death or moderate to severe neurodevelopmental impairment at 22–26 months’ corrected age, with a particularly strong association for cognitive delay. While causality cannot be inferred, the findings underscore the clinical importance of preventing, detecting, and managing AKI in the NICU and incorporating AKI history into neurodevelopmental follow-up planning. Future work should clarify mechanisms, improve neonatal AKI ascertainment, and test interventions to reduce both kidney and brain injury in this vulnerable population.

Funding and clinicaltrials.gov

The PENUT trial was supported by the National Institutes of Health and other funders as detailed in the primary trial publication. Trial registration: ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier NCT01378273. The secondary analysis referenced here was performed using PENUT trial data and analyzed in February 2024.

References

1. Hanna M, Chock VY, Kamath N, Raj A, Swanson JR, Griffin R, Askenazi DJ, Nesargi S. Acute Kidney Injury and Neurodevelopmental Outcomes in Extremely Premature Neonates: A Secondary Analysis of a Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2025 Nov 3;8(11):e2543270. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2025.43270.

2. Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Acute Kidney Injury Work Group. KDIGO Clinical Practice Guideline for Acute Kidney Injury. Kidney Int Suppl. 2012;2:1–138.

3. Jetton JG, Askenazi DJ. Acute kidney injury in the neonate. Clin Perinatol. 2014 Jun;41(3):487–502. doi:10.1016/j.clp.2014.03.002.