Highlights

Visceral adipose tissue, muscle fat infiltration, and liver fat are universal drivers of accelerated cardiovascular ageing across both sexes. Subcutaneous abdominal fat and android fat mass are associated with increased cardiovascular age-delta specifically in males. Genetic evidence from Mendelian randomization indicates that gynoid fat distribution may provide a protective effect against cardiovascular senescence.

Background: The Intersection of Obesity and Cardiovascular Senescence

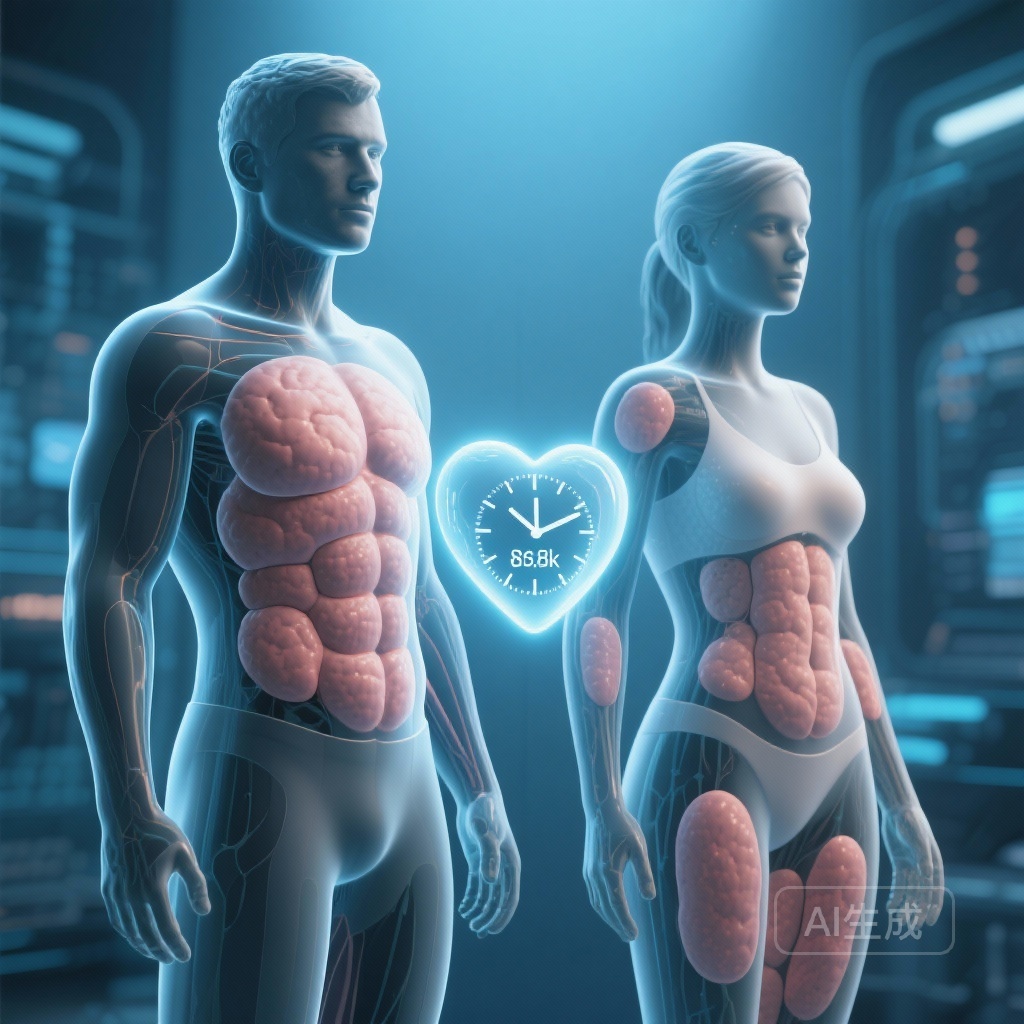

Cardiovascular ageing is defined as the progressive loss of physiological reserve within the heart and vasculature. This process is not merely a function of chronological time but is heavily modified by environmental, genetic, and metabolic factors. Over time, accumulated damage across diverse cell types and tissues leads to multi-morbidity and increased mortality. While obesity has long been recognized as a risk factor for premature ageing, the traditional reliance on Body Mass Index (BMI) often obscures the complex physiological reality of adipose tissue. Not all fat is created equal; its metabolic activity and impact on the cardiovascular system depend heavily on its anatomical distribution. This study sought to move beyond simple anthropometric measures to determine how sex-dependent fat phenotypes influence human cardiovascular ageing using advanced imaging and machine learning.

Study Design and Methodology

The researchers conducted a comprehensive analysis of 21,241 participants from the UK Biobank, a large-scale prospective cohort study. To quantify cardiovascular ageing, the team employed machine learning algorithms to analyze 126 image-derived traits (IDTs) obtained from cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) imaging. These traits encompassed vascular function, cardiac motion, and myocardial fibrosis. By training the model on these parameters, the researchers could predict a cardiovascular age for each participant. The primary metric used was the cardiovascular age-delta, calculated as the difference between the predicted cardiovascular age and the participant’s actual chronological age. A positive age-delta indicates a cardiovascular system that appears older than its chronological counterpart.

Quantifying Adipose Distribution

The volume and distribution of body fat were assessed using whole-body imaging. The study focused on several key phenotypes: visceral adipose tissue (VAT), abdominal subcutaneous adipose tissue (ASAT), liver fat fraction (LFF), muscle adipose tissue infiltration (MATI), and android/gynoid fat masses. The association between these fat phenotypes and the cardiovascular age-delta was assessed using multivariable linear regression, adjusting for age and sex. Furthermore, two-sample Mendelian randomization (MR) was utilized to investigate whether these associations were potentially causal rather than merely correlative.

Key Findings: The Topography of Fat and Aging

The study revealed that specific fat depots have a disproportionate impact on the biological age of the heart and vessels. The results demonstrate a clear hierarchy in how fat distribution influences cardiovascular senescence.

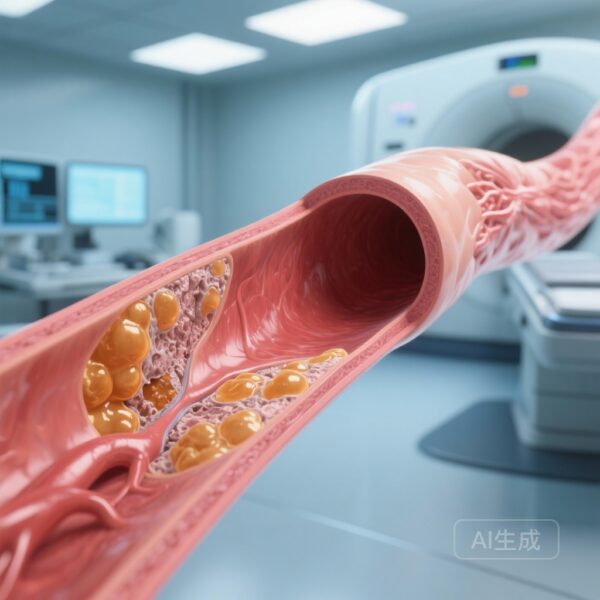

Universal Drivers of Ageing

Three specific fat phenotypes emerged as the strongest predictors of an increased cardiovascular age-delta in both men and women: liver fat fraction, visceral adipose tissue volume, and muscle fat infiltration. Liver fat fraction showed the most significant impact, with a β coefficient of 1.066 (95% CI, 0.835-1.298, P < .0001). Visceral adipose tissue followed closely (β = 0.656, 95% CI, 0.537-0.775, P < .0001), emphasizing that fat stored around the internal organs is far more detrimental than total body fat. Muscle adipose tissue infiltration (MATI) also showed a significant positive association (β = 0.183, 95% CI, 0.122-0.244, P = .0003), suggesting that ectopic fat within skeletal muscle contributes to systemic cardiovascular decline.

Sex-Specific Dimorphism

A striking finding of the study was the sex-specific impact of certain fat depots. Abdominal subcutaneous adipose tissue (ASAT) and android fat mass (fat typically stored around the trunk and upper body) were significantly associated with increased cardiovascular age-delta only in males. In men, android fat mass showed a strong positive association (β = 0.983, 95% CI, 0.64-1.326, P < .0001). In contrast, these same fat depots did not demonstrate the same deleterious effect on the cardiovascular age of female participants, suggesting that women may have a higher physiological tolerance for subcutaneous fat or that hormonal profiles (such as estrogen) modulate the inflammatory response of these tissues.

The Protective Role of Gynoid Fat

Perhaps the most intriguing result came from the analysis of gynoid fat (fat stored around the hips and thighs). Genetically predicted gynoid fat, assessed through Mendelian randomization, showed an association with a decreased cardiovascular age-delta. This suggests that the biological pathways involved in storing fat in the gynoid region may actually be protective against the structural and functional changes associated with cardiovascular ageing.

Mechanistic Insights and Clinical Implications

The study provides robust evidence that the metabolic health of the cardiovascular system is intimately linked to where fat is stored. Ectopic fat, particularly in the liver and around viscera, is known to be pro-inflammatory and metabolically active, releasing adipokines and fatty acids directly into the portal circulation. This contributes to systemic inflammation, insulin resistance, and eventually, structural changes in the myocardium and arterial stiffness. The male-specific vulnerability to android and subcutaneous fat suggests that clinicians should be particularly vigilant when assessing cardiovascular risk in men with central adiposity, even if their BMI remains within a relatively moderate range. Conversely, the potential protective effect of gynoid fat aligns with the gluteofemoral fat hypothesis, which posits that this depot acts as a metabolic sink, sequestering harmful fatty acids away from the heart and liver.

Expert Commentary: Shifting the Clinical Paradigm

This research highlights the limitations of BMI as a clinical tool for assessing cardiovascular health. While BMI is easy to calculate, it fails to capture the nuances of fat distribution that this study proves are critical for predicting biological ageing. The use of machine learning and advanced imaging allows for a much more granular understanding of a patient’s cardiovascular trajectory. By identifying patients with high visceral or liver fat early, clinicians can implement targeted lifestyle interventions or pharmacological treatments (such as GLP-1 receptor agonists or SGLT2 inhibitors) that specifically target ectopic fat reduction. However, it is important to note that while the UK Biobank is a powerful resource, it primarily consists of individuals of European descent, and further research is needed to determine if these sex-specific fat patterns hold true across more diverse ethnic and racial groups.

Conclusion

The study by Losev et al. establishes that cardiovascular ageing is not a uniform process but is shaped by the topography of body fat. The discovery that visceral and ectopic fat are universal drivers of ageing, while subcutaneous fat effects are sex-dependent, provides a new framework for personalized cardiovascular medicine. Recognizing that gynoid fat may offer protective benefits further complicates and enriches our understanding of adipose tissue function. Ultimately, targeting the distribution and metabolic function of adipose tissue—rather than just total weight—will be essential for interventions aimed at extending the healthy human lifespan.

References

Losev V, Lu C, Tahasildar S, et al. Sex-specific body fat distribution predicts cardiovascular ageing. Eur Heart J. 2025;46(46):5076-5088. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehaf553.