Highlights

– Zalunfiban, a subcutaneous glycoprotein IIb/IIIa (αIIbβ3) inhibitor given at first medical contact, improved a 30‑day hierarchical clinical composite in patients with ST‑elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI).

– Zalunfiban accelerated preintervention coronary patency (improved corrected frame count) and lowered the chance of worse outcomes in a multicomponent ranking model (adjusted odds ratio 0.79; 95% CI 0.65–0.98; P=0.028).

– Severe or life‑threatening bleeding (GUSTO severe) was not increased, but mild‑to‑moderate bleeding was more frequent with zalunfiban (6.4% vs 2.5%; P<0.001).

Background and clinical need

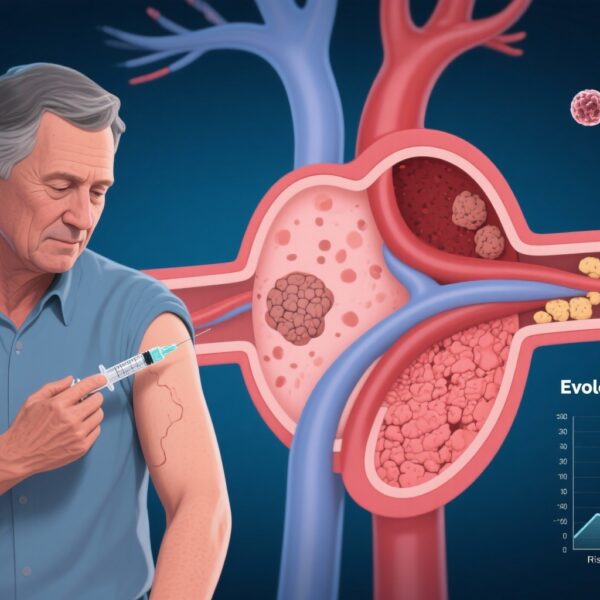

ST‑segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) is a time‑sensitive condition in which early restoration of coronary blood flow reduces infarct size, preserves left ventricular function, and improves short‑ and long‑term outcomes. Primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) is the preferred reperfusion strategy when it can be performed in a timely fashion. Yet, even with rapid door‑to‑balloon care, substantial myocardial injury may occur before mechanical reperfusion. Pharmacologic approaches that limit thrombotic burden prior to angiography—particularly antiplatelet agents—have the potential to improve initial vessel patency, reduce distal embolization during PCI, and improve clinical outcomes.

Intravenous glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors (αIIbβ3 antagonists) were developed to block final common pathway platelet aggregation and have shown benefits in some PCI settings, at the cost of increased bleeding in certain populations. Zalunfiban is a novel formulation designed for subcutaneous administration at first medical contact (including prehospital settings), aiming to provide rapid platelet inhibition without the logistic constraints of intravenous therapy.

Study design

The CELEBRATE trial (NCT04825743) was an international, randomized, double‑blind, placebo‑controlled study enrolling patients with suspected STEMI. A total of 2,467 patients were randomized in a 1:1:1 ratio to receive a single subcutaneous injection of zalunfiban at 0.11 mg/kg (n=853), zalunfiban at 0.13 mg/kg (n=818), or placebo (n=796) at first medical contact. Treatment was intended to be given before angiography and primary PCI.

The primary efficacy outcome was assessed using a hierarchical proportional odds model that ranked seven clinical and physiologic end points from worst to best across 30 days: (1) all‑cause death, (2) stroke, (3) recurrent myocardial infarction, (4) acute stent thrombosis, (5) new‑onset heart failure or rehospitalization for heart failure, (6) larger infarct size, and (7) no end point through 30 days. This type of ranked composite places greater weight on the most clinically consequential events.

The primary safety end point was severe or life‑threatening bleeding according to the GUSTO criteria. Prespecified secondary assessments included angiographic measures of preintervention infarct‑related artery patency and procedural findings.

Key findings

Primary efficacy

When zalunfiban arms were pooled versus placebo, the trial found a statistically significant improvement in the hierarchical 30‑day composite: adjusted odds ratio (OR) 0.79 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.65 to 0.98; P=0.028). An odds ratio below 1.0 in this proportional odds framework indicates a lower likelihood of being in a worse category on the ranked outcome scale with zalunfiban compared with placebo.

Angiographic outcomes

Preintervention angiography demonstrated faster coronary blood flow in the zalunfiban group versus placebo. The corrected frame count of the infarct‑related artery was significantly lower (improved) with zalunfiban: median 109 (interquartile range [IQR] 35–176) versus 176 (IQR 40–176) for placebo (P=0.012). Improved frame count suggests greater patency and flow before mechanical reperfusion.

Bleeding and safety

GUSTO severe or life‑threatening bleeding occurred in 1.2% of zalunfiban‑treated patients versus 0.8% of placebo recipients (P=0.40), a difference that did not reach statistical significance. However, GUSTO mild‑to‑moderate bleeding was more frequent with zalunfiban: 6.4% versus 2.5% with placebo (P<0.001). Thus, zalunfiban increased less‑severe bleeding events but did not appear to increase the predefined severe bleeding metric within 30 days.

Other clinical events

Although the hierarchical model integrates several clinical events and physiologic measures, the published result centers on the pooled comparison versus placebo. Absolute event rates for each individual component were not the primary determinant of the trial conclusion; the hierarchical analysis emphasizes clinically major outcomes such as death, stroke, and reinfarction above laboratory or imaging endpoints.

Interpretation and biological plausibility

Zalunfiban targets the αIIbβ3 integrin on platelets, blocking the final common pathway for platelet aggregation. Subcutaneous dosing at first medical contact is designed to achieve early systemic platelet inhibition before coronary instrumentation and reperfusion, theoretically reducing thrombus burden, improving spontaneous or pharmacologically aided vessel patency, and decreasing distal embolization during PCI.

The observed improvement in corrected frame count supports the mechanistic expectation that platelet inhibition before angiography leads to improved preintervention coronary flow. The overall favorable effect on the ranked 30‑day composite suggests that earlier pharmacologic platelet inhibition with zalunfiban can translate into clinically meaningful benefits at 30 days.

Clinical implications

If adopted into practice, zalunfiban could change early STEMI care by enabling a standardized, easily administered antiplatelet strategy at first medical contact (prehospital or emergency department) without requiring intravenous access or infusion pumps. This approach may be particularly useful in systems where prehospital diagnosis and transport-to‑PCI times are variable and in patients at high thrombotic risk.

However, translation into routine care would require consideration of multiple factors: integration with existing antiplatelet regimens (e.g., aspirin and P2Y12 inhibitors), timing relative to administration of potent oral or intravenous P2Y12 inhibitors or cangrelor, patient selection to minimize bleeding risk, and logistics for paramedics and emergency physicians.

Strengths

The CELEBRATE trial was randomized, placebo‑controlled, double‑blind, and international, enhancing internal validity and generalizability across healthcare systems. The pragmatic design—administering a single subcutaneous dose at first medical contact—addresses a real‑world implementation question. The use of a hierarchical endpoint appropriately weights major clinical events while integrating physiologic measures such as infarct size and vessel patency.

Limitations

Several caveats temper enthusiasm. First, the primary analysis pooled two doses of zalunfiban against placebo; dose‑response effects and optimal dosing require further exploration. Second, the hierarchical composite, while clinically thoughtful, can be complex to interpret—improvements may be driven by physiologic measures rather than large reductions in mortality or stroke. Third, follow‑up was limited to 30 days; longer‑term effects on mortality, heart failure, and stent thrombosis are unknown. Fourth, although severe bleeding was not increased, the rise in mild‑to‑moderate bleeding could affect patient experience and resource use (e.g., additional monitoring, transfusions in some cases). Finally, the trial was funded by the manufacturer (CeleCor Therapeutics), and industry sponsorship warrants independent replication.

Where this fits in current practice and guidelines

Current STEMI guidelines emphasize rapid reperfusion, dual antiplatelet therapy, and individualized anticoagulation strategies. Established intravenous αIIbβ3 inhibitors have been used selectively in high‑risk PCI settings, but routine upstream use has not been widely adopted because of bleeding concerns and mixed effects on hard outcomes. The possibility of an effective subcutaneous αIIbβ3 antagonist that can be administered at first contact—without increasing severe bleeding—represents an important evolution, but guideline incorporation will require confirmatory studies, assessment of interactions with modern P2Y12 strategies, and health‑system implementation research.

Research and practice gaps

Key questions for further investigation include: Which patient subgroups derive the greatest net benefit (e.g., anterior MI, large thrombus burden, long transport times)? What is the optimal dosing and timing relative to other antiplatelet agents, including oral P2Y12 inhibitors and intravenous agents like cangrelor? Will benefits persist beyond 30 days, influencing mortality and heart‑failure outcomes? How does zalunfiban perform in routine practice when administered by emergency medical services rather than in controlled trial settings?

Conclusion

The CELEBRATE trial indicates that subcutaneous zalunfiban administered at first medical contact in STEMI improves pre‑PCI coronary patency and reduces the likelihood of a worse 30‑day hierarchical clinical outcome compared with placebo, without a statistically significant increase in severe bleeding but with more mild‑to‑moderate bleeding. These results support the biologic rationale for early potent platelet inhibition and suggest a potential new tool for prehospital STEMI care. Confirmation in independent studies, longer follow‑up, and careful integration into contemporary antiplatelet strategies will be necessary before broad guideline adoption.

Funding and trial registration

Funded by CeleCor Therapeutics. CELEBRATE ClinicalTrials.gov number: NCT04825743.

References

1) Van’t Hof AWJ, Gibson CM, Rikken SAOF, et al. Zalunfiban at First Medical Contact for ST‑Elevation Myocardial Infarction. NEJM Evidence. 2025 Nov 10:EVIDoa2500268. doi: 10.1056/EVIDoa2500268. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 41211981.

2) Ibanez B, James S, Agewall S, et al. 2017 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST‑segment elevation. Eur Heart J. 2018;39(2):119–177.

3) O’Gara PT, Kushner FG, Ascheim DD, et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA Guideline for the Management of ST‑Elevation Myocardial Infarction. Circulation. 2013;127:e362–e425.