Highlight

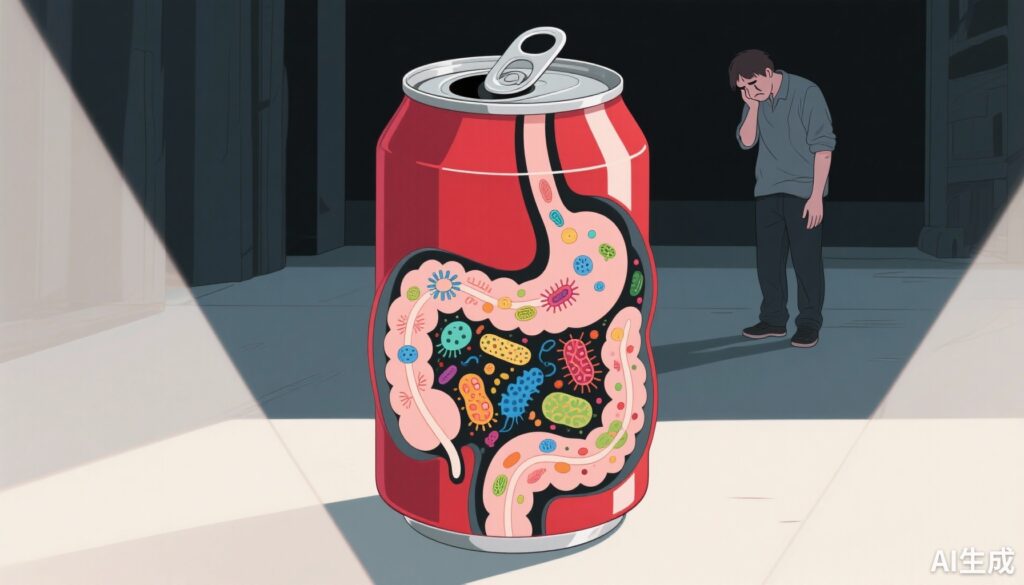

This multicenter cohort study identifies a positive association between soft drink consumption and major depressive disorder (MDD) diagnosis and symptom severity, with stronger effects noted in women. Notably, the gut microbiome genus Eggerthella mediates part of this relationship. These findings suggest possible microbiome-targeted interventions in depression, emphasizing public health measures to reduce soft drink intake.

Study Background and Disease Burden

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is a leading cause of disability worldwide, profoundly impacting quality of life and socioeconomic productivity. While nutritional and lifestyle factors have been increasingly recognized as contributors to depression risk, the specific role of soft drink consumption remains ambiguous. Soft drinks, commonly rich in sugar, caffeine, and additives, are frequently linked to negative physical health outcomes such as obesity and metabolic syndrome. Recent evidence hints at their potential adverse influence on mental health, yet the biological mechanisms underlying these associations are incompletely understood.

The gut-brain axis is an emerging paradigm linking gastrointestinal microbiota to neuropsychiatric outcomes, deepening understanding of depression pathophysiology. Certain gut bacteria are hypothesized to modulate neuroinflammation, neurotransmitter synthesis, and stress responsiveness. In this context, alterations in specific gut microbiota genera may represent a mechanistic intermediate between dietary exposures like soft drink intake and depressive symptoms. However, few large-scale cohort studies have rigorously explored such mediation, especially focusing on bacteria such as Eggerthella and Hungatella, which have been implicated in microbiome shifts related to depression.

Study Design

This investigation utilized cross-sectional data from the Marburg-Münster Affective Cohort, collected between September 2014 and September 2018 across multiple centers in Germany. The sample comprised 405 clinically diagnosed patients with MDD and 527 healthy controls, age 18-65 years, recruited from the general population and primary care settings. Data analysis was conducted between May and December 2024.

Soft drink consumption was assessed quantitatively alongside clinical diagnosis and symptom severity of MDD. Gut microbiota profiles, focusing on Eggerthella and Hungatella abundance, were determined through sequencing-based analyses controlling for technical covariates such as library size. Primary statistical approaches involved multivariable regression and analysis of variance (ANOVA), adjusting for important confounders including site and education level, with mediation analyses employed to test whether microbiota alterations mediated the soft drink–MDD relationship.

Key Findings

The study population consisted of 405 individuals with MDD (67.9% female; mean age 36.37 years) and 527 healthy controls (65.5% female; mean age 35.33 years).

- Soft Drink Consumption Predicts MDD Diagnosis and Severity: After adjustments, soft drink consumption was significantly associated with higher odds of MDD diagnosis (odds ratio [OR], 1.081; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.008–1.159; P = .03). Symptom severity was also positively correlated (P < .001; partial eta squared [ηp2], 0.012), indicating small but significant effect sizes.

- Gender Differences: These associations were notably stronger in women (diagnosis: OR, 1.167; 95% CI, 1.054–1.292; P = .003; severity: P < .001; ηp2, 0.036), suggesting potential sex-specific vulnerability or behavioral patterns influencing risk.

- Gut Microbiota Changes: Among women, increased soft drink consumption correlated with elevated abundance of the genus Eggerthella (P = .007; ηp2, 0.017), but no significant association was detected with Hungatella abundance.

- Mediation Analyses: Eggerthella abundance significantly mediated the relationship between soft drink intake and both MDD diagnosis (P = .011) and symptom severity (P = .005). This mediation explained roughly 3.82% and 5.00% of the total effect respectively, indicating that gut microbiota partially accounts for the observed association.

While the effect sizes of mediation were modest, this biologically plausible pathway underscores the relevance of the gut microbiome in mood disorders.

Expert Commentary

The study by Thanarajah et al. represents a critical step forward in unraveling the complex interplay among diet, gut microbiota, and depression. The identification of Eggerthella as a mediator aligns with prior microbiome research implicating this genus in inflammatory processes and neuroactive metabolite production potentially relevant to depression pathogenesis.

The stronger effects observed in females raise important queries about sex-linked biological or psychosocial moderators in dietary influences on mental health. However, given the cross-sectional design, causality cannot be definitively established, and reverse causation remains plausible; depressed individuals might consume more soft drinks as a coping mechanism.

These findings warrant replication in prospective cohorts and intervention trials to evaluate whether reducing soft drink intake or modulating Eggerthella abundance can alleviate depressive symptoms. Additionally, comprehensive characterization of the gut microbiome beyond individual taxa will refine understanding of microbial network effects.

Limitations include potential residual confounding by unmeasured lifestyle or dietary factors and reliance on cross-sectional analyses. Nonetheless, this research provides a valuable framework for microbiota-informed depression prevention strategies.

Conclusion

This study provides compelling evidence that soft drink consumption associates with increased risk and severity of major depressive disorder, with gut microbiota alterations—especially in Eggerthella abundance—partially mediating this effect. From a clinical and public health standpoint, reducing soft drink intake may serve as a practical approach to lessen depression risk. Moreover, targeting gut microbiome alterations presents a promising avenue for novel therapeutic interventions in depression.

Future longitudinal and interventional studies are needed to establish causality and develop microbiome-based clinical applications. Meanwhile, clinicians should consider integrating dietary counseling focused on beverage consumption when managing patients with or at risk for depression.

References

- Thanarajah S, Ribeiro AH, Lee J, et al. Soft Drink Consumption and Depression Mediated by Gut Microbiome Alterations. JAMA Psychiatry. 2025 Sep 24:e252579. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2025.2579. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 40991280; PMCID: PMC12461599.

- Destefano Shields C, Arora T, Cermakova P. Gut microbiome and depressive symptoms: epidemiological evidence and potential mechanisms. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;89:200-211.

- Clarke G, O’Mahony SM, Dinan TG, Cryan JF. Priming for health: Gut microbiota acquired in early life regulates particulate matter-induced neuroinflammation and behavior. Transl Psychiatry. 2014;4:e398.

- Jiang H, Ling Z, Zhang Y, et al. Altered fecal microbiota composition in patients with major depressive disorder. Brain Behav Immun. 2015;48:186-194.