Introduction and Context

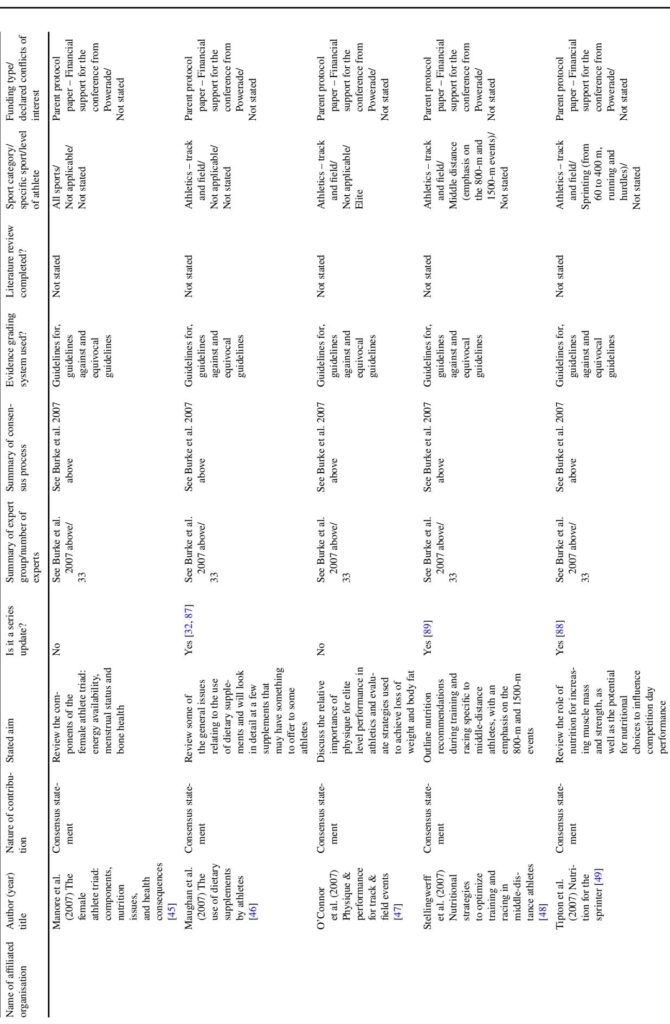

The manipulation of body mass and body composition—reducing fat mass, increasing fat-free mass, or both—is a routine part of competitive sport. In 2025 Delany and colleagues published a large scoping review that collated dietary recommendations from 73 consensus statements, position stands and a practice guideline produced by international expert groups (Delany et al., Sports Med. 2025). The review synthesises recommendations across many organisations (e.g., IOC, ACSM, ISSN, World Athletics/IAAF, World Aquatics/FINA) and identifies points of agreement, areas of uncertainty, and opportunities to make guidance more actionable.

Why now? The field has matured rapidly: new data on energy availability (EA), protein dosing, timing strategies, and the safety/efficacy of some supplements have changed practice. Concerns about athlete health (disordered eating, RED-S/relative energy deficiency in sport), anti-doping risk and implementation gaps in real-world settings created an imperative to summarise and harmonise expert guidance. Delany et al. did that by mapping recommendations and highlighting where guidance is precise (e.g., EA thresholds) and where it remains vague (e.g., many calorie and carbohydrate directives).

This article summarises the core, practice-facing recommendations emerging from that scoping review, explains what changed over time, highlights controversies and implementation barriers, and offers clinicians and sport practitioners a usable, evidence-aligned blueprint to manage athlete body-mass and composition goals safely and effectively.

New Guideline Highlights (Key Takeaways)

– Safety and team-based care: Always involve a qualified sports dietitian/nutritionist and a multidisciplinary team (minimum: sports dietitian/nutritionist, strength/conditioning coach, sports medicine physician, psychologist when indicated). (Delany et al., 2025; IOC RED-S, 2014)

– Individualised, realistic targets: Goals must be athlete-centred and sport-specific, accounting for sex, age, genetics, playing position and phase of season.

– Protect energy availability: Minimum EA commonly adopted across expert documents = 30 kcal/kg fat-free mass (FFM)/day to reduce health risk. Avoid chronic EA below this threshold. (Loucks et al., 2011; Mountjoy et al., 2014)

– Rate and timing: Aim for gradual changes. For fat/fat mass loss, commonly recommended rate = 0.5–1.0 kg per week (0.5–1.0 kg/week may be used as a practical upper limit). Prefer off-season or pre-season periods for larger changes; periodise composition across the training year.

– Macronutrient framing:

– Protein: 1.6–2.4 g/kg/day is the contemporary consensus range (particularly in energy deficit to preserve FFM). Distribute protein across 3–6 feeds/day, with ~0.25–0.5 g/kg per meal (or 20–40 g absolute doses depending on body size) and peri-workout intake emphasized. (Delany et al., 2025; Jäger et al., 2017)

– Carbohydrate: Periodise to training demands. Broad practical range 3–12 g/kg/day depending on session volume/intensity; lower end (≈3–6 g/kg) often used during energy-restriction phases.

– Fat: Less often specified; recommendations typically emphasise maintaining overall diet quality and avoiding extreme reductions (<15% of total energy) that could impair hormonal or micronutrient status.

– Supplements: Most athletes do not need supplements. Where used, consensus supports evidence-based, targeted options: creatine (ergogenic for FFM & strength), whey/quality protein supplements for convenience, and short-term multi-vitamin/mineral when diet is restrictive. Discourage unproven products and those with anti-doping risk. (IOC supplements consensus, 2018; ISSN position stands)

– Behavioural and implementation gap: Many consensus documents phrase recommendations vaguely (e.g., “adequate calories”) rather than as concrete behaviours. Embedding behavioural science and specifying actionable steps (what, who, when, where, how) was widely recommended as a next step.

Updated Recommendations and Key Changes (Compared with Earlier Guidance)

Delany et al. tracked how recommendations evolved. Highlights:

– Protein recommendations narrowed and became more specific. Earlier guidance offered wide ranges or absolute meal sizes; recent consensus (post-2014) coalesced around 1.6–2.4 g/kg/day for body-composition goals and explicit per-meal targets (≈0.25–0.5 g/kg/meal). (Phillips & van Loon, 2011; Jäger et al., 2017; Witard et al., 2019)

– Energy-availability concept matured and gained consensus. By 2011–2014 an EA threshold of ~30 kcal/kg FFM/day became widely recommended to protect physiological function; that has been reiterated in later documents (Loucks et al., 2011; Mountjoy et al., 2014; Delany et al., 2025).

– Creatine guidance reversed early ambivalence to near-universal conditional support. Older documents noted insufficient evidence; recent ISSN and society position stands endorse creatine as safe and effective for increasing FFM and strength in many athletes (Kreider et al., 2017; Buford et al., 2007).

– Fluid restriction for weight loss has been de-emphasised. Earlier practices used dehydration for acute drops; contemporary guidance warns against routine fluid restriction and emphasises health risks, with any acute dehydration only for very short, competition-specific scenarios under clinical oversight. (Delany et al., 2025; ACSM/Weight-category guidance)

– More sport-specific guidance exists now (e.g., distance-running, sprinting, aquatic sports, football), but many sports remain under-represented and much guidance is still generalist in tone.

Table — Snapshot of Key Changes (older → newer)

– Protein per day: 1.0–2.5 g/kg (variable) → 1.6–2.4 g/kg (narrower consensus)

– Energy availability: early concept → standardised minimum EA ≈ 30 kcal/kg FFM/day

– Creatine: cautious/insufficient → evidence-backed support for many athletes

– Fluid restriction: occasional accepted practice → generally discouraged except short-term, supervised use

Topic-by-Topic Recommendations

Below are distilled, actionable recommendations based on the scoping review and the primary consensus documents it synthesised.

1. Goal-setting and assessment

– Who decides: Targets should be set collaboratively—athlete, sports dietitian, coach, sports physician; include psychologist when body-image or disordered eating risks exist. (IOC RED-S, 2014)

– Assessment: Choose validated body-composition methods appropriate for the context, and document measurement error. Use multi-modal assessment where possible (e.g., DEXA, skinfolds with trained assessor, BIA with standardised protocol). Interpret values against sport- and position-specific reference ranges, not population norms. (Ackland et al., 2012; Delany et al., 2025)

– Target framing: Use ranges rather than fixed numbers; prioritise performance and health (e.g., power:mass ratio) rather than aesthetic goals. Consider genetics, sex, age and career stage.

– Safety limits: Avoid advising body fat below ~5% for men and ~12% for women as routine targets; recognise individual variation and that optimal performance may be achieved above these minimums. (Delany et al., 2025; Manore et al., 2007)

2. Energy and Energy Availability (EA)

– Definition reminder: EA = (energy intake − exercise energy expenditure) / kg FFM.

– Minimum recommended EA: Aim to keep EA ≥ 30 kcal/kg FFM/day to protect endocrine function, bone health and performance, and to reduce RED-S risk. Avoid prolonged reductions below this level. (Loucks et al., 2011; Mountjoy et al., 2014)

– Calorie manipulation: To increase mass, create a surplus commonly quoted as +500–1000 kcal/day (individualise). To reduce mass, implement a deficit between −250 to −1000 kcal/day depending on starting weight, sport and athlete status—smaller deficits for lighter athletes to preserve EA. Monitor weekly changes and adjust. (Delany et al., 2025; ACSM, 2021)

3. Protein

– Daily target: 1.6–2.4 g/kg/day (strong consensus in recent position stands for body-composition goals and FFM preservation during energy restriction). Many papers recommend the 1.6–2.4 range for both gaining muscle and maintaining FFM when losing fat. (Jäger et al., 2017; Witard et al., 2019; Delany et al., 2025)

– Distribution: Spread intake across 3–6 meals; aim for ~0.25–0.5 g/kg/meal or absolute doses of 20–40 g high-quality protein per meal (adjust for body mass). Include protein in the pre- and post-exercise periods and consider a pre-sleep protein dose for overnight MPS support when appropriate. (Phillips & van Loon, 2011; Witard et al., 2019)

– Types: Prioritise high-quality, whole-food protein sources; use whey or other supplements for convenience when diet cannot meet needs.

4. Carbohydrate

– Periodise to training: Daily recommendations vary with workload: ~3–12 g/kg/day. Use higher intakes for high-volume training and lower intakes during reduced-load/responsive fat-loss phases. During calorie restriction, favour the lower end (e.g., 3–6 g/kg/day) while ensuring training quality is maintained.

– Around sessions: Emphasise carbohydrate availability for key sessions; strategies include targeted carbs pre-, during (when prolonged), and post-exercise for recovery and adaptation.

5. Fat, Fibre, Micronutrients, Fluid

– Fat: Typically 15–30% of energy; avoid extreme reductions (<15%) that may impair fat-soluble vitamin absorption, reproductive hormones and energy density.

– Fibre: Monitor as high-fibre intake in energy-restricted athletes can reduce overall energy intake; temporarily reduce fibre intake before weigh-ins if clinically appropriate and supervised.

– Micronutrients: Athletes in restricted diets may need monitoring and possible supplementation (iron, calcium, vitamin D, B vitamins, zinc). Aim for dietary adequacy first.

– Fluid: Ensure hydration supports training and competition. Avoid dehydration strategies for routine weight loss; any acute dehydration must be supervised and short term.

6. Supplements

– Recommended/conditionally supportive:

– Creatine monohydrate: evidence supports improvements in strength, FFM and repeated-power tasks. Typical loading 15–20 g/day for 5–7 days followed by maintenance 3–5 g/day; many athletes use 3–5 g/day without loading. (Kreider et al., 2017)

– High-quality protein powders (e.g., whey) for convenience and meeting protein targets.

– Multi-vitamin/mineral: short-term use when diet is restrictive.

– Discouraged or not routinely recommended:

– Many weight-loss-specific supplements with weak evidence (e.g., carnitine, chromium) and products with contamination risk. Use third-party tested products when supplements are necessary. (Maughan et al., 2018; Delany et al., 2025)

7. Rates, Timing and Periodisation

– Fat loss: Aim for gradual loss—0.5–1.0 kg/week commonly recommended; slower rates may better preserve FFM, especially in lighter athletes.

– Mass gain: Aim for steady gains with a modest surplus (≈+250–1000 kcal/day depending on athlete size and desired rate), with strength training stimulus to favour FFM gains over fat.

– Season timing: Large composition changes are best planned for off-season or general/preparation phases. Acute, small adjustments may be used in-season but prioritise performance and health.

– Periodisation: Plan cyclical adjustments to energy and carbohydrate to align with training cycles and competition demands.

8. Special Populations

– Female athletes: Recognise sex-specific physiology (menstrual function, bone health) and heightened RED-S risk. Apply EA monitoring and be cautious with aggressive energy restriction. (Mountjoy et al., 2014; Sims et al., ISSN, 2023)

– Weight-category and combat sports: Use sport-specific, medically supervised protocols. Prefer gradual adjustments early in the season; any acute weight-cutting must be minimised and monitored. ACSM expert consensus (Burke et al., 2021) emphasises health-protective approaches.

– Endurance vs power vs team sports: Adjust carbohydrate and energy strategies to match high-volume endurance training versus power/strength-focused programs.

Expert Commentary and Insights

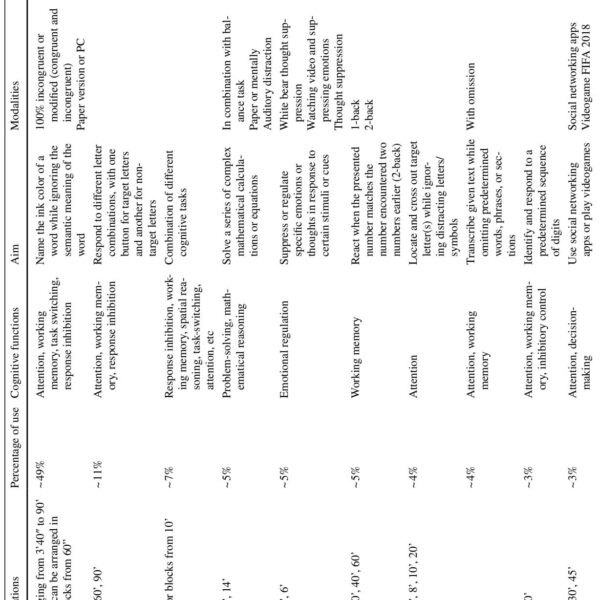

Delany et al. synthesised input from 328 experts across 25 countries. Their review surfaced several recurrent expert perspectives and contested issues:

– Consensus areas: The field broadly agrees on team-based care, individualised targets, EA ≥30 kcal/kg FFM/day as a health guardrail, prioritising protein and periodised carbohydrate, and cautious, evidence-based supplement use (creatine, whey). These form a practical scaffold for safe practice.

– Vague language and implementation gap: Many documents use nonspecific terms—”adequate”, “sufficient”, “appropriate”—which leaves front-line practitioners to interpret and operationalise recommendations. Experts highlighted the need for behaviourally anchored guidance (What specific behaviors should an athlete change? How and when?) and for more sport- and position-specific operational tools.

– Evidence grading varies: Some organisations used formal evidence-grading systems (e.g., ADA Evidence Analysis Library, ISSN adapted grading), but many consensus statements did not report transparent grading. Experts signalled the need for more consistently graded guidance to inform clinical confidence.

– Athlete involvement: Only a handful of consensus groups included athletes in development panels. Experts increasingly recommend co-design with athletes to improve practicality, acceptability and adherence.

– Controversies: Optimal protein dose per meal, safe minimal EA for short-term interventions in men vs women, and the role of ketogenic diets for body-composition goals are areas of active debate. Recent ISSN and sport-specific position stands (e.g., ISSN ketogenic diet 2024; Delany et al., 2025) emphasise that ketogenic approaches can reduce body mass but may impair high-intensity performance and reduce FFM in some contexts.

Practical Implications for Clinicians and Practitioners

A concise operational checklist drawn from the review for sports clinicians and dietitians:

1. Assemble the team: sport dietitian/nutritionist + coach + physician (psychologist when indicated).

2. Baseline assessment: body composition (method & error), dietary intake, training load, medical history, menstrual status in female athletes, and screening for disordered eating/RED-S.

3. Agree goals: define performance-relevant, realistic ranges (not single numbers); document rationale and timeframe.

4. Protect EA: calculate estimated EA and avoid chronic EA <30 kcal/kg FFM/day; adjust deficits/surplus to maintain safe EA where possible.

5. Macronutrient plan: aim protein 1.6–2.4 g/kg/day with distributed meals; periodise carbohydrate 3–12 g/kg/day to match training; avoid excessive fat restriction.

6. Rate & monitor: target 0.5–1.0 kg/week for fat loss when reasonable; monitor training quality, recovery, mood, menstrual function, and biomarkers where indicated (iron, vitamin D, bone turnover if relevant).

7. Supplements: follow evidence—creatine and whey where indicated; use third-party tested products; avoid unproven fat-loss supplements.

8. Behavioural plan: translate dietary prescriptions into behavioural steps (meal plans, shopping lists, routines) and use behaviour-change techniques (goal setting, monitoring, feedback).

9. Update & communicate: review every 1–2 weeks early in a programme, then monthly; communicate changes clearly to athlete and coaching staff.

Vignette: Applying the Consensus

Alex is a 24-year-old male lightweight rower (70 kg) who needs to lose 3 kg of body mass across 6 weeks before the national trials while maintaining FFM and race power.

Using the consensus:

– Team: sports dietitian + coach + sports physician agree goals.

– EA calculation: Aim to keep EA ≥30 kcal/kg FFM/day. If Alex’s FFM is 58 kg, minimum EA ≈ 1,740 kcal/day.

– Calorie plan: Create a modest deficit of ~300–500 kcal/day, aiming for ~0.5 kg/week loss; this preserves EA and supports training.

– Protein: Target 1.8–2.0 g/kg/day ≈ 126–140 g/day, spread across 4 meals (≈30–35 g/meal) with post-training protein.

– Carbs: Periodise carbs to training days (≈4–6 g/kg/day on heavy days; lower on light days) to support session quality.

– Supplements: Use whey for convenience if whole-food protein can’t meet needs, and consider creatine when off-season for strength gains (but avoid if it increases body mass above weight-class limits).

– Monitoring: Weekly body-mass checks, session-RPE and training quality, mood, and menstrual function not applicable here; check iron status if fatigue emerges.

This approach aligns performance and health priorities, uses consensus targets, and translates them into clear behavioural steps.

Gaps, Controversies and Future Directions

– Need for sport-specific, behaviourally specific guidance: Consensus documents often lack concrete implementation steps. Future guidelines should specify “what to do” (e.g., exact meal plans, timing strategies) and use behavioural technique taxonomies to improve adherence.

– Evidence grading and transparency: A move toward consistently graded recommendations (GRADE-style) across organisations would help clinicians weigh benefits vs harms.

– Under-represented sports and populations: Many sports lack tailored guidance; athletes with disabilities were excluded from the Delany et al. review and require dedicated recommendations.

– Implementation science: Research is needed into how well consensus recommendations translate into practice, barriers/facilitators, and the real-world effectiveness of recommended rates and macronutrient targets.

Conclusions

Delany et al.’s 2025 scoping review synthesises a large, diverse literature of expert statements and position stands into a coherent set of practical priorities: prioritise athlete safety and multidisciplinary care; individualise and realistically set targets; protect energy availability (EA ≥30 kcal/kg FFM/day); adopt gradual, periodised approaches to calorie manipulation; deliver protein at the higher end of the range (≈1.6–2.4 g/kg/day) with distributed feeding; periodise carbohydrate to match training; and use supplements sparingly and evidence-based (creatine, whey). To improve implementation, future guidance should be regularly updated, sport-specific, and behaviourally explicit.

Clinicians and practitioners should use these consensus-derived principles as a scaffold and operationalise them in partnership with athletes, applying measurement, monitoring and behavioural techniques to protect athlete health while optimising performance.

References (selected)

– Delany LV, Costello N, Jones B, Backhouse SH. Dietary Recommendations for Body Mass and Composition Manipulation in Male and Female Athletes: a Scoping Review of Consensus Statements, Position Stands and Practice Guidelines from International Expert Groups. Sports Med. 2025 Aug 21. doi:10.1007/s40279-025-02285-4 IF: 9.4 Q1 .- Mountjoy M, Sundgot-Borgen J, Burke L, Carter S, Constantini N, Lebrun C, et al. The IOC consensus statement: beyond the female athlete triad—relative energy deficiency in sport (RED-S). Br J Sports Med. 2014;48(7):491–497. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2014-093502 IF: 16.2 Q1 .- Loucks AB, Kiens B, Wright HH. Energy availability in athletes. J Sports Sci. 2011;29(Suppl 1):S7–S15. doi:10.1080/02640414.2011.615119 .- Thomas DT, Erdman KA, Burke LM; American College of Sports Medicine; Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics; Dietitians of Canada. Nutrition and Athletic Performance. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2016 Mar;48(3):543–568. doi:10.1249/MSS.0000000000000852 IF: 3.9 Q1 .- Jäger R, Kerksick CM, Campbell BI, Cribb PJ, Wells SD, Skwiat TM, et al. International Society of Sports Nutrition position stand: protein and exercise. J Int Soc Sports Nutr. 2017 Dec 1;14:20. doi:10.1186/s12970-017-0187-6 IF: 3.9 Q1 .- Kreider RB, Kalman DS, Antonio J, Ziegenfuss TN, Wildman R, Collins R, et al. International Society of Sports Nutrition position stand: safety and efficacy of creatine supplementation in exercise, sport, and medicine. J Int Soc Sports Nutr. 2017 Nov 15;14:18. doi:10.1186/s12970-017-0173-z IF: 3.9 Q1 .- Burke LM, Castell LM, Casa DJ, Close GL, Costa RJS, Melin AK, et al. International Association of Athletics Federations consensus statement 2019: nutrition for athletics. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab. 2019;29(2):73–84. doi:10.1123/ijsnem.2019-0002 IF: 2.6 Q2 .- Maughan RJ, Burke LM, Dvorak J, Larson-Meyer DE, Peeling P, Phillips SM, et al. IOC consensus statement: dietary supplements and the high-performance athlete. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab. 2018 Apr;28(2):104–125. doi:10.1123/ijsnem.2018-0021 .- Burke LM, Slater GJ, Matthews JJ, Langan-Evans C, Horswill CA. American College of Sports Medicine expert consensus statement on weight loss in weight-category sports. Curr Sports Med Rep. 2021;20(4):199–217. doi:10.1249/JSR.0000000000000808 IF: 1.4 Q3 .

(For full bibliographic detail and the complete list of documents reviewed, see Delany et al., 2025.)