Introduction and Context

Acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGIB) remains a common, potentially life‑threatening emergency. While endoscopy is the diagnostic and often therapeutic cornerstone, the optimal timing of endoscopy—especially when patients present with varying degrees of hemodynamic instability—remains debated. Major society guidelines emphasize early endoscopy but provide limited, sometimes non‑specific guidance on how to tailor timing to hemodynamic status. The recent international survey by Obeidat and colleagues (analyzed responses from 533 clinicians across 50 countries) provides an important real‑world snapshot of how practicing physicians interpret hemodynamic risk and choose endoscopy timing in both variceal and non‑variceal UGIB (NVUGIB and VUGIB) (Obeidat et al., 2025).

This article synthesizes the survey’s findings, places them alongside existing guideline statements from major societies (ESGE, ACG/ASGE, hepatology consensus statements), and offers a pragmatic, graded set of recommendations for clinicians and systems. It focuses on the core clinical question the survey addressed: how should hemodynamic status determine the urgency of endoscopy for UGIB?

New Guideline Highlights (Survey‑Derived Consensus)

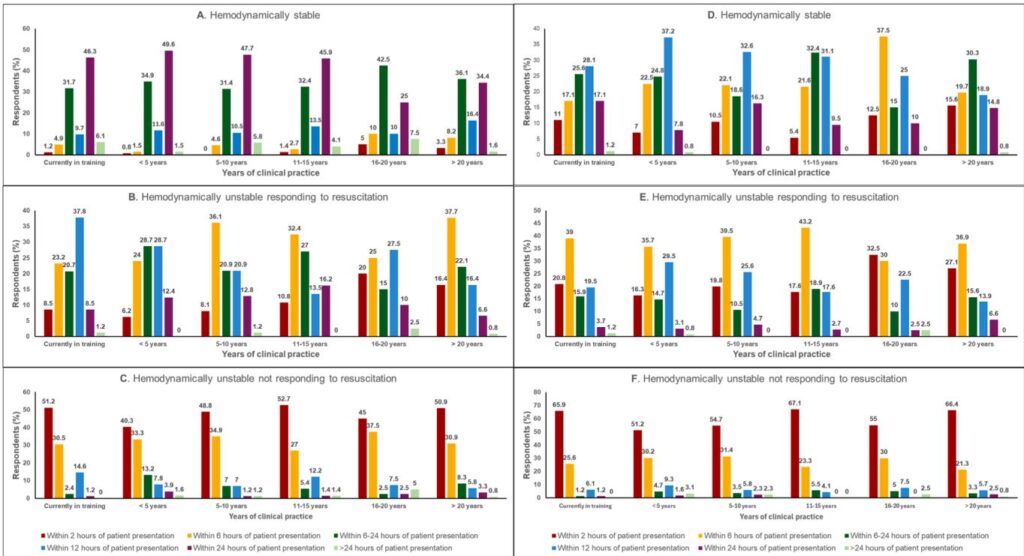

– Overarching principle: The more hemodynamically unstable the patient, the earlier clinicians favor endoscopy. The international survey showed a consistent stepwise shift to earlier endoscopy as instability increases, with most clinicians recommending urgent endoscopy (within 2 hours) for patients not responding to resuscitation, and routine early endoscopy (within 24 hours) for stable patients (Obeidat et al., 2025).

– Key time bands reflected in clinician practice: within 2 hours (immediate/very urgent), within 6 hours (urgent), within 12 hours (early urgent), within 24 hours (standard early), and >24 hours (delayed). These bands map intuitively to clinical scenarios and resource planning.

– Variceal vs non‑variceal differences: For suspected variceal bleeding, clinicians were more likely to favor earlier intervention compared with non‑variceal bleeding when hemodynamic instability was present—consistent with the higher likelihood of massive hemorrhage and need for targeted therapy in variceal bleeding (Obeidat et al., 2025; de Franchis et al., 2022).

– Experience, hospital type and volume matter: Senior clinicians, university centers and high‑volume units tended to favor earlier endoscopy for unstable patients; less experienced clinicians and community/private hospitals showed more variability and often opted for longer observation windows (Obeidat et al., 2025).

Updated Recommendations and Key Changes Compared with Prior Guidelines

The survey does not replace formal society guidelines but supplements them with practice patterns and clinician reasoning. Comparing this survey-derived consensus with existing guidelines clarifies gaps and suggests refinements:

– Existing guideline baseline:

– ACG/ASGE (Laine et al., 2021) and ESGE (Gralnek et al., 2021/2022) recommend early endoscopy—frequently within 24 hours—for most patients with UGIB, with recognition that high‑risk patients may benefit from more urgent procedures. However, precise triggers tied to specific hemodynamic definitions are not uniformly prescriptive.

– Hepatology and portal hypertension guidance (Baveno VII, de Franchis et al., 2022; Kaplan et al., 2024) emphasize early vasoactive therapy and endoscopic therapy for variceal hemorrhage, but the exact timing under different resuscitation responses remains variably defined.

– What this survey adds:

– Operationalizes urgency bands to real practice preferences and highlights how many clinicians equate “not responding to resuscitation” with immediate (<2 hour) endoscopy, and “responding” with urgent (≤6–12 hour) endoscopy.

– Demonstrates heterogeneity in definitions of hemodynamic instability (though a majority use systolic blood pressure 100 bpm ± syncope/orthostasis/organ hypoperfusion), pointing to an important target for consensus standardization.

– Suggested update to guidance language (practical proposal): Formal guidelines should (1) adopt a clear hemodynamic stratification (stable, unstable‑responding, unstable‑nonresponding), (2) link these strata to recommended endoscopy timing bands (2 h, 6 h, 12 h, 24 h), and (3) emphasize local resource readiness (24‑hour endoscopy, interventional radiology) and team roles (GI, anesthesia/ICU, IR) when urgent procedures are considered.

Topic‑by‑Topic Recommendations

Below are practical, evidence‑informed recommendations integrating the survey results with current society statements. Where possible, recommendations indicate the level of evidence or consensus strength—many areas remain driven by expert opinion rather than randomized trials.

1) Defining Hemodynamic Status (practical working definitions)

– Hemodynamically stable: systolic blood pressure (SBP) ≥100 mm Hg, heart rate (HR) ≤100 bpm, no syncope, no orthostatic drop, and no signs of organ hypoperfusion.

– Hemodynamically unstable — responding to resuscitation: initial SBP 100 bpm or syncope/orthostasis/clinical signs of bleeding but responds to initial resuscitation (fluid boluses, blood transfusion guided by hemoglobin and symptoms), with stabilization of vital signs and perfusion markers.

– Hemodynamically unstable — not responding to resuscitation: persistent hypotension or ongoing large‑volume bleeding despite initial resuscitation attempts, ongoing transfusion requirement, or continuing signs of organ hypoperfusion (e.g., altered mental status, rising lactate).

Note: A majority of clinicians in the survey used the SBP 100 or syncope/orthostasis/organ hypoperfusion definition—but up to one third used narrower criteria, highlighting variability (Obeidat et al., 2025). Adoption of standardized definitions will improve research and guideline clarity (Gralnek et al., 2021; Laine et al., 2021).

2) Risk stratification tools and initial assessment

– Immediate assessment: airway, breathing, circulation. Simultaneously determine likely source (variceal vs non‑variceal), comorbidities, medications (anticoagulants/antiplatelets), and signs of ongoing hemorrhage.

– Use validated risk scores: Glasgow‑Blatchford Score (GBS) for triage of low vs high risk; Rockall (pre‑ and post‑endoscopy) for rebleeding/mortality risk. Most clinicians should incorporate a risk score early, though the survey found only ~60% used a score routinely—an area for improvement (Obeidat et al., 2025) (Laine et al., 2021).

3) Resuscitation, transfusion and co‑therapy before endoscopy

– Resuscitate before endoscopy: establish large‑bore IV access, crystalloid resuscitation as needed, and blood transfusion guided by restrictive transfusion thresholds (target Hb 7–8 g/dL in most patients; consider higher targets—8–9 g/dL—for ischemic heart disease or ongoing massive bleeding) following contemporary randomized data and guideline recommendations (Laine et al., 2021).

– Pharmacologic therapy: For suspected variceal bleeding — start vasoactive agents (terlipressin, somatostatin analogs, or octreotide) promptly and administer prophylactic antibiotics (as per hepatology guidance) before endoscopy (de Franchis et al., 2022; Kaplan et al., 2024).

– Reversal of anticoagulation/antiplatelets: follow specific guidance depending on agent and bleeding severity (consult hematology/thrombosis protocols). Do not delay essential endoscopy in life‑threatening bleeds when reversal would take time.

4) Recommended endoscopy timing by hemodynamic category (practical algorithm)

– Hemodynamically stable (NVUGIB or VUGIB): aim for endoscopy within 24 hours (standard early endoscopy). Most clinicians preferred this timing for stable NVUGIB; for VUGIB some favored earlier (6–12 h) due to risk profile (Obeidat et al., 2025). This aligns with ESGE and ACG recommendations (Gralnek et al., 2021; Laine et al., 2021).

– Hemodynamically unstable — responding to resuscitation:

– NVUGIB: aim for urgent endoscopy within 6–12 hours. Survey responses clustered around 6–12 hours, with more experienced physicians preferring earlier intervention (Obeidat et al., 2025).

– VUGIB: aim for endoscopy within 6 hours (many clinicians favored within 6 h), after stabilization and initiation of vasoactive agents and antibiotics (de Franchis et al., 2022).

– Hemodynamically unstable — not responding to resuscitation (ongoing massive hemorrhage): prioritize resuscitation but plan for immediate endoscopy within 2 hours (very urgent) if the procedure can be delivered safely with appropriate anesthesia/airway support and transfusion capacity. Most surveyed clinicians (47.8% NVUGIB; 60% VUGIB) chose endoscopy within 2 hours for this scenario (Obeidat et al., 2025). If endoscopy is not feasible or unsuccessful, engage interventional radiology (angiography/embolization) or surgical teams emergently.

Rationale and evidence: Prospective randomized data on exact timing are limited. Observational studies and guideline statements consistently support early (within 24 h) endoscopy for most patients and urgent endoscopy for those with ongoing bleeding or hemodynamic instability (Laine et al., 2021; Gralnek et al., 2022). The survey documents how clinicians interpret and operationalize these recommendations in real practice.

5) Specific considerations for variceal bleeding (VUGIB)

– Immediate measures: vasoactive drugs and antibiotics on presentation; arrange urgent endoscopy once airway and resuscitation are controlled.

– Timing: earlier endoscopy is generally preferred—many experts and the survey support endoscopy within 6 hours for unstable but responding patients and within 2 hours for those not responding (Obeidat et al., 2025). Endoscopic variceal ligation (EVL) is the standard endoscopic therapy; if endoscopy is delayed or fails, consider transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) in high‑risk patients (de Franchis et al., 2022; Kaplan et al., 2024).

6) Non‑variceal bleeding (NVUGIB) specifics

– Peptic ulcer bleeding remains the most common NVUGIB cause. Endoscopic hemostasis (clips, thermal, injection) should be performed during the index procedure when indicated.

– Timing: stable patients—within 24 hours; unstable but responding—preferably within 6–12 hours; unstable and not responding—within 2 hours if feasible (Obeidat et al., 2025). Observational literature suggests very early endoscopy (<6 h) does not clearly improve mortality in stable patients but is reasonable where ongoing bleeding is evident (Laursen et al., 2017; Laine et al., 2021).

7) Anesthesia, airway and sedation considerations

– Patients who are actively bleeding or severely unstable often require general anesthesia or intubation for airway protection during urgent endoscopy. This requires coordination with anesthesia and ICU teams. The survey highlighted that sedation‑related complications are a concern in unstable patients and influence clinician willingness to perform immediate procedures (Obeidat et al., 2025).

8) Interventional radiology (IR) and surgery: when endoscopy fails or is not feasible

– Availability of timely IR varies (survey: IR available to ~55% of respondents). For ongoing life‑threatening bleeding not controlled endoscopically, IR embolization and emergency surgery are critical backups; guidelines stress early multidisciplinary involvement (Gralnek et al., 2021; Laine et al., 2021).

9) Special populations

– Cirrhosis and portal hypertension: prioritize vasoactive drugs and antibiotics; lower thresholds for urgent endoscopy and early consideration of salvage therapy (TIPS) for uncontrolled bleeding (de Franchis et al., 2022).

– Elderly or frail patients: balance endoscopy urgency against comorbidities and procedural risks; shared decision‑making and early involvement of multidisciplinary teams recommended.

– Antithrombotic therapy users: individualized approach guided by bleeding severity, thrombotic risk, and specialist input.

10) Follow‑up and secondary prevention

– After successful endoscopic hemostasis, institute cause‑specific secondary prevention: for peptic ulcer disease—eradicate H. pylori and stop or modify NSAIDs/antiplatelets where possible; for variceal bleeding—start secondary prophylaxis (non‑selective beta‑blocker plus EVL per hepatology guidelines) (de Franchis et al., 2022; Kaplan et al., 2024).

– Early outpatient follow‑up and clear discharge instructions are essential for preventing rebleeding and readmission.

Expert Commentary and Insights

The international survey’s authors and advisory group include experienced endoscopists, hepatologists and intensivists. Their combined perspective yields several practical insights:

– Standardize the definition of hemodynamic instability. The survey shows variability; a common, operational definition (as suggested above) will reduce practice heterogeneity and improve research and guideline clarity (Obeidat et al., 2025).

– Prioritize systems readiness. The therapeutic benefits of earlier endoscopy depend on having 24‑hour endoscopy staffing, anesthesia availability for high‑risk cases, and access to IR and surgery. High‑volume university centers more often recommend very early endoscopy because they have infrastructure—smaller hospitals must develop transfer protocols and clear triage criteria (Obeidat et al., 2025).

– Experience matters. Senior clinicians more commonly favor earlier intervention in unstable patients. Mentorship, simulation and protocols can increase junior clinicians’ comfort with urgent procedures and harmonize care.

– Evidence gaps persist. Randomized trials comparing specific timing bands (e.g., ≤2 h vs 6–12 h in unstable but responding patients) are lacking. Observational data, principles of hemostasis, and expert consensus drive current practice. The survey identifies research priorities: outcomes by defined hemodynamic strata, the role of immediate endoscopy in ongoing transfusion‑dependent bleeds, and resource‑sensitive pathways.

Controversies and dissenting views identified by the authors include:

– Whether immediate endoscopy in profoundly unstable patients meaningfully improves mortality beyond rapid resuscitation plus temporizing measures. Some clinicians worry about procedural risk without stabilization; others emphasize that definitive hemostasis as soon as possible can be life‑saving.

– The optimal timing for stable high‑risk patients (e.g., high GBS but clinically stable): some clinicians favor very early endoscopy (<12 h) while others endorse a more measured approach within 24 h.

Practical Implications

For clinicians and hospital systems, translating the survey’s findings into practice suggests several actionable steps:

1) Institutional protocol and triage algorithm

– Adopt a local protocol that defines hemodynamic categories (stable, unstable‑responding, unstable‑nonresponding) and ties each to an expected endoscopy timing band (e.g., 24 h, 6–12 h, ≤2 h respectively).

– Include triggers for escalation: transfusion of >4 units in 6 h, persistent hypotension despite resuscitation, or ongoing active hematemesis should prompt activation of an urgent endoscopy/IR/surgery pathway.

2) Team readiness

– Ensure 24‑hour on‑call endoscopy and formal pathways for anesthesia/intubation when urgent procedures are needed.

– Map local IR and surgical backup capabilities; create fast transfer agreements with higher‑level centers where necessary.

3) Education and quality assurance

– Train junior staff in triage principles and simulation of urgent endoscopy scenarios; audit timing and outcomes to identify barriers.

– Encourage routine use of risk scores (GBS, Rockall) to support triage decisions—only ~60% of surveyed clinicians used them regularly (Obeidat et al., 2025).

4) Resource‑sensitive adaptations

– In resource‑limited settings or where IR is unavailable, the thresholds and strategies for transfer versus immediate endoscopy must be explicit. Early discussion with tertiary centers and telemedicine consultation can help.

Patient Vignette (Illustrative Application)

John Davis, a 62‑year‑old man with known peptic ulcer disease, arrives at a community emergency department with large‑volume hematemesis. On arrival his SBP is 86 mm Hg, HR 115 bpm. He is given two large‑bore IVs, crystalloids and two units of packed red cells; after resuscitation his SBP improves to 106 mm Hg and HR to 96 bpm. The ED team initiates IV PPI, calls gastroenterology and activates the urgent endoscopy pathway. Based on the patient’s unstable but responding status, the recommended approach would be urgent endoscopy within 6 hours to identify and treat the bleeding lesion. If he had remained hypotensive and requiring ongoing transfusion despite resuscitation, the team would have aimed for immediate endoscopy (within 2 hours) if anesthesia support and transfusion capability were available; otherwise rapid transfer to a tertiary center with IR and surgical backup would be arranged.

This vignette reflects the survey’s majority practice patterns and aligns with an evidence‑informed, resource‑aware approach (Obeidat et al., 2025; Laine et al., 2021).

Future Directions and Research Needs

The survey highlights several priorities:

– Standardized definitions of hemodynamic instability and use of core outcome sets for timing studies.

– Randomized or pragmatic trials comparing different timing bands in clearly defined hemodynamic strata (e.g., ≤2 h vs 6–12 h in unstable‑responding patients) with mortality, rebleeding, transfusion need and complication endpoints.

– Implementation research on how to expand 24‑hour endoscopy capability safely and equitably, including teleconsultation and regionalized care models.

– Studies of the role and timing of early IR and of combined strategies (endoscopy + early TIPS) in high‑risk variceal bleeding.

Conclusions

The international survey of 533 clinicians provides a pragmatic, practice‑based roadmap: hemodynamic status should be the principal determinant of endoscopy timing in UGIB. Stable patients are generally managed with endoscopy within 24 hours; patients who are unstable but responding to resuscitation are best served by urgent endoscopy within roughly 6–12 hours (earlier for suspected variceal hemorrhage); patients not responding to resuscitation usually require immediate endoscopy within 2 hours if safe and feasible, with rapid escalation to IR or surgery when necessary.

These practice patterns complement existing guideline recommendations (ESGE, ACG, hepatology statements) and underscore the need for standardized definitions, local protocols, team readiness, and targeted research to refine timing strategies. Hospitals should translate these consensus‑based principles into clear triage algorithms, ensure multidisciplinary coverage for urgent cases, and monitor outcomes to improve care for this common and consequential emergency.

References

– Obeidat M, Floria DE, Teutsch B, Abonyi‑Tóth Z, Hegyi P, Erőss B; International Advisory Group of The Survey. Hemodynamic Status as a Determinant Factor of Optimal Endoscopy Timing in Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding: Results From an International Survey of 533 Clinicians. Gastroenterology. 2025 Oct 20:S0016‑5085(25)05899‑8. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2025.07.044. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 41114679.

– Laine L, Barkun AN, Saltzman JR, et al. ACG Clinical Guideline: Management of Patients With Acute Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding. Am J Gastroenterol. 2021;116(5):899–917. doi:10.14309/ajg.0000000000001229.

– Gralnek IM, Dumonceau JM, Kuipers EJ, et al. Diagnosis and management of nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Guideline—Update 2021/2022. Endoscopy. 2021;53(5):300–332. (Updated 2022 statement: Endoscopy. 2022;54:1094–1120.)

– de Franchis R, et al. Baveno VII — Renewed recommendations on the management of portal hypertension. J Hepatol. 2022;76(1):959–974.

– Kaplan DE, et al. [AASLD/Hepatology portal hypertension guidance]. Hepatology. 2024;79:1180–1211.

– Laursen SB, et al. Timing of endoscopy in upper gastrointestinal bleeding and outcomes: a systematic review and meta‑analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2017;85:936–944.e3.

– Prosenz J, et al. Variability in practice patterns for acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding: a survey. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2023;58:856–862.

(Readers should consult full society guideline documents—ESGE, ACG, AASLD/EASL and local clinical protocols—for detailed, prescriptive guidance.)