Introduction and Context

Physical activity is one of the most effective interventions for preventing chronic disease, yet a small risk of serious adverse events—mainly cardiovascular and musculoskeletal—accompanies higher-intensity or new exercise. In response to gaps in guidance for non‑elite adults who plan to start or resume intensive exercise, the German Society for Sports Medicine and Prevention (DGSP) led a multi‑society consensus to produce the S2k guideline “Sports Preparticipation Evaluation for Healthy Adults” (Joisten et al., Sports Med 2025) [Joisten 2025].

Why now? Existing PPE guidance mostly targets elite athletes or provides divergent recommendations for middle‑aged adults (ACSM, EFSMA, EACPR). The German panel sought to fill a practical gap: how to screen apparently healthy adults (≥18 years) who intend to begin or increase the intensity/volume of exercise while balancing feasibility, cost, and the harms from overtesting. The guideline is consensus (S2k) rather than a full systematic evidence review—reflecting limited primary trial data—but it draws on 35 prior guidelines and 55 cited primary studies.

This article summarizes the core recommendations, explains what changed from prior practice, highlights controversies and expert views, and outlines pragmatic implications for clinicians and health services.

New Guideline Highlights

– Target population: apparently healthy adults planning to start or return to regular or higher‑intensity exercise (not elite athletes with separate pathways).

– Key principle: prioritize a structured medical and sports history plus targeted physical examination; perform additional tests only if history/exam indicate abnormal findings or elevated risk.

– Cardiovascular triage: use validated 10‑year risk scores (e.g., SCORE2, Arriba) from age 35 to objectify risk; resting 12‑lead ECG recommended if no recent ECG or if indicated by history/exam (moderate grade).

– Imaging and stress testing: echocardiography and exercise testing are not routine—use them selectively when structural disease or exercise‑induced symptoms or high pretest probability exist.

– Fitness as a vital sign: cardiopulmonary exercise testing (CPET) and simple muscle strength measures (handgrip) are optional tools to guide individualized training and risk stratification.

– Counseling & behavior change: results from PPE should be used to give individualized FITT‑VP (frequency/intensity/time/type/volume/progression) prescriptions and motivational interviewing to encourage safe uptake of activity.

– Resource and evidence limits recognized: the guideline calls for national registries and cohort studies to evaluate PPE impact and cost‑effectiveness.

Key takeaway for clinicians: do a thorough standardized history (medical, family, sports), a whole‑body focused physical examination, calculate cardiovascular risk where appropriate, and reserve ECG, echocardiography, labs, stress tests and CPET for those with red flags or high pretest probability. Use the PPE visit as an opportunity to prescribe exercise safely.

Updated Recommendations and Key Changes

Compared with prior athlete‑focused or older screening frameworks, the German consensus introduces several notable shifts:

– Population focus: explicit guidance for “healthy adults” returning to or beginning more intense exercise rather than elite/competitive athletes. This reframes PPE as a public‑health tool for recreational sports and fitness programs.

– Primary reliance on history + physical exam: the guideline places a stronger emphasis on structured history and whole‑body physical examination as the primary screening modality; additional testing is conditional rather than routine.

– ECG stance nuanced: unlike the Italian model that advocated routine ECG in athletes, this guideline recommends a 12‑lead resting ECG when no recent ECG exists or if history/exam indicate concern (moderate recommendation). The panel recognized the proven benefit in some athlete programs but balanced it against false positives and resource implications in broader populations.

– Selective imaging: transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) is recommended only where structural heart disease is suspected (strong recommendation for selective use), not as a routine test.

– Fitness measurement: the guideline endorses using CPET selectively to quantify cardiorespiratory fitness and to guide training (weak recommendation), and supports simple muscular fitness measures (e.g., handgrip) as useful adjuncts.

– Behavioral counseling integration: strong mandate to use PPE findings to craft individualized exercise prescriptions and apply evidence‑based behavior change techniques (motivational interviewing, action planning).

Evidence drivers: the panel used the limited direct evidence available (e.g., Corrado et al. on ECG and sudden cardiac death reduction in athletes, SAFER race screening data, ACSM algorithms), but decisions reflect pragmatic cost–benefit considerations and stakeholder surveys on feasibility and acceptability.

Top Recommendations (Condensed)

– Offer PPE to adults planning to start or expand regular or high‑intensity exercise (Recommendation 1; grade: moderate).

– Use a standardized PPE process centered on:

– Comprehensive personal & family medical history (including COVID‑19 history where relevant), medication and supplement use, and sports history (FITT framework).

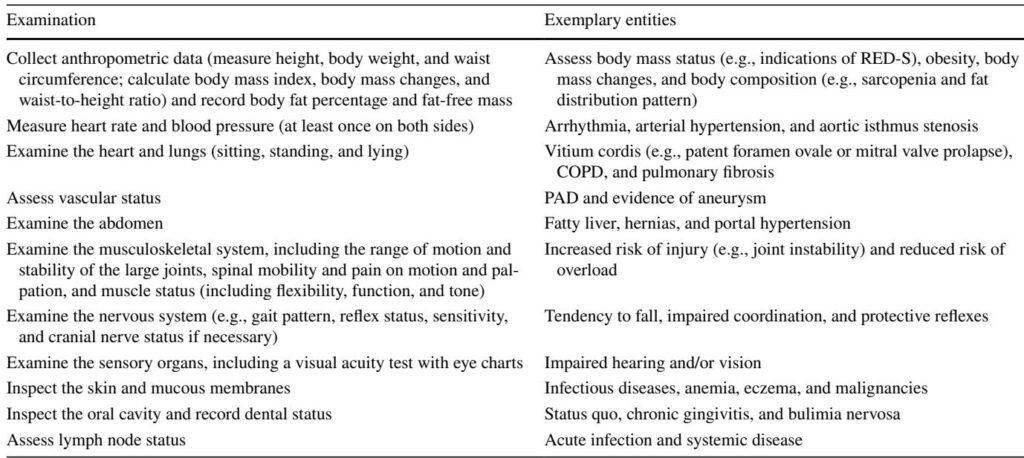

– Whole‑body physical exam (anthropometry, heart/lung auscultation, vascular check, abdominal exam, musculoskeletal and neurological screening, vision/hearing when relevant).

– From age 35, calculate cardiovascular risk with a validated instrument (SCORE2, Arriba); use this to triage further evaluation (Recommendation 8; strong).

– Perform a 12‑lead resting ECG if no recent ECG exists or if history/exam indicate (Recommendation 14; moderate).

– Reserve TTE and exercise testing for those with suspected structural disease, exercise‑induced symptoms, or elevated pretest probability (Recommendations 15 and 16).

– Use CPET selectively to quantify cardiorespiratory fitness and guide training (Recommendation 17; weak). Measure muscular fitness (handgrip) as a useful surrogate (Recommendation 18; weak).

– Limit laboratory or other instrumental tests to cases with indication from history/exam (Recommendation 13 and 19; weak to strong depending on scope).

– Refer patients with significant joint pathology, instability, or prior major injuries/arthroplasties to relevant specialists; monitor those with implants regularly (Recommendations 11–12).

– During counseling, assess risk to self and others, and advise on safe participation or modification when necessary (Recommendation 20; strong).

Topic‑by‑Topic Recommendations (More Detail)

1) Who should be offered a PPE

– Adults intending to start regular exercise or substantially increase intensity/volume. The guideline deliberately does not require PPE for all light or moderate activity nor make a one‑size‑fits‑all screening program mandatory.

2) Structure of the PPE

– Use a standardized medical history form covering family cardiovascular history (including sudden cardiac death 10%) or alarming symptoms/findings: consider additional testing (resting ECG if not recent; TTE if structural disease suspected; exercise ECG or advanced imaging if ischemia suspected).

4) Resting 12‑lead ECG

– Recommendation: perform if there is no recent resting ECG or if indicated by history/exam (moderate grade). Interpretation should follow athlete‑appropriate criteria where relevant, and clinicians should be aware of interpretation challenges and false positives.

5) Echocardiography and stress testing

– TTE: selective—use when structural disease suspected, new murmur, or unexplained findings.

– Exercise ECG: selective—use when exercise‑induced symptoms, suspected ischemia, or to assess exercise tolerance for high‑intensity plans. Achieve maximal effort where diagnostic utility is sought.

6) Laboratory testing

– No routine panels for all. Consider CBC, glucose/HbA1c, lipids, liver/renal function, electrolytes and urine testing when history/exam indicate or if risk scores require lipid or glycemic data. Athlete‑specific tests (ferritin, vitamin D) should be targeted by clinical indication.

7) Fitness testing

– CPET: helpful but not routine—use to quantify maximal oxygen uptake, differentiate dyspnea etiologies, and set training zones when warranted.

– Muscle strength: handgrip or simple functional tests can inform prescriptions and predict risk; include especially for older adults.

8) Musculoskeletal management and referral

– Immediate referral to orthopedics/rehab for joint swelling, instability, major ROM restriction, or spine knock/pain with neuro signs. Patients with joint replacements or significant prior injuries require specialist monitoring and tailored activity plans.

9) Counseling and exercise prescription

– Translate PPE findings into individualized FITT‑VP prescriptions. Incorporate behavior change techniques (motivational interviewing, goal setting, action planning). PPE visits should motivate safe initiation and progression rather than create barriers.

Expert Commentary, Controversies and Implementation Challenges

Consensus strengths and tensions

– Broad agreement on the primacy of history and exam and on using PPE to prescribe individualized exercise (100% consensus for many items). Strong consensus also supported restricting advanced tests to indicated cases.

– Areas of contention included the degree to which PPEs should be offered to all adults. DEGAM (family medicine) raised concerns that a broad PPE program could divert scarce primary care resources, create barriers to exercise, and generate harms from false positives. Consequently, Recommendation 1 is a moderate rather than strong recommendation.

ECG debate

– The Italian experience (Corrado et al., JAMA 2006) supports routine ECG in athletes to reduce sudden cardiac death incidence; however, extrapolating this to the general adult population raises issues of low prevalence, false positives and resource implications. The German panel therefore adopted a middle path: ECG when no recent recording exists or when prompted by history/exam.

Resource and training limitations

– A practical limitation is the variable availability of clinicians trained in sports medicine. Germany relies on course‑based qualifications rather than wide specialty coverage, and many countries lack sports medicine specialists. The guideline notes that interpretation of athlete ECGs and subtle sports‑related findings may require sports cardiology expertise or decision support (including validated AI tools) to reduce unnecessary referrals.

False positives and overdiagnosis

– For rare conditions, even tests with good sensitivity/specificity yield low positive predictive values. The panel explicitly warns about follow‑up cascades from nonspecific abnormal findings and recommends cautious, indication‑based testing.

Research gaps and need for registries

– The evidence base lacks randomized or registry data showing PPEs reduce mortality or serious morbidity in recreational adult populations. The guideline prioritizes establishing national/regional registries and cohorts (e.g., a FRIEND‑like registry extended to muscular fitness) to track outcomes, NNT/NNP, and cost‑effectiveness.

Practical Implications for Clinicians and Health Systems

For primary care and sports medicine clinicians

– Implement a standardized history and physical examination form for PPE visits. Use age‑appropriate risk tools (SCORE2) and document sports goals and planned intensity to guide triage.

– Reserve resting ECG, stress testing, echo, CPET and lab testing for individuals with warning features or elevated pretest risk.

– Use the PPE visit to give an individualized exercise prescription and apply brief motivational interviewing techniques—this could shift many patients from inactivity to sustainable, safe physical activity.

For occupational health & community programs

– PPE should not be a barrier to starting activity. Consider low‑threshold entry for light/moderate activities while targeting PPE resources to those planning higher‑intensity or prolonged exertion or who are older/have risk factors.

System and policy considerations

– Training in sports medicine competencies for primary care clinicians will improve PPE quality. Decision support (ECG interpretation algorithms validated in athletes and adults) and teleconsultation with sports cardiologists could help manage abnormal screening findings without unnecessary referrals.

– Establish registries to capture events (sudden cardiac arrest, serious injuries) and evaluate PPE effectiveness and health economic impact.

Illustrative Patient Vignette

Mark is 48, previously sedentary, and plans to train for his first half‑marathon. He has well‑controlled hypertension on an ACE inhibitor and a family history of coronary artery disease (father MI at 62). He reports occasional exertional chest discomfort over several weeks. Mark books a PPE.

Applying the guideline:

– History: detailed sports history (FITT), medication, family history, and exertional symptoms documented.

– Risk score: SCORE2 is calculated (using BP and lipids if available); with age and risk factors, Mark falls into an intermediate–high risk category. This flags need for further cardiac evaluation.

– Exam: focused cardiac and vascular exam performed; BP measured bilateral; basic musculoskeletal screen normal.

– Tests: resting 12‑lead ECG ordered (no recent ECG available). Because of exertional symptoms and elevated pretest risk, the clinician refers for echocardiography and an exercise ECG or cardiopulmonary exercise test to evaluate ischemia and exercise tolerance.

– Counseling: while awaiting tests, Mark receives an individualized FITT‑VP plan focusing initially on low‑ to moderate‑intensity walking and cross‑training, and is counseled on symptom escalation (stop and seek care for chest pain/syncope). The clinician uses brief motivational interviewing to set goals and plan progressive training once clearance is documented.

This practical pathway mirrors the guideline’s emphasis on history & exam‑driven triage, targeted testing for risk and symptoms, and the use of PPE to craft a safe training plan.

Research and Quality‑Improvement Priorities

The guideline identifies clear research priorities:

– Registry studies linking PPE findings to later adverse outcomes (sudden cardiac arrest, myocardial infarction, major musculoskeletal injuries) to estimate NNP/NNP and cost‑effectiveness.

– Prospective cohort studies to determine whether fitness measures (CPET, handgrip) improve risk prediction beyond standard risk scores.

– Trials of PPE‑based counseling interventions measuring behavior change (increased activity), injuries, and cardiovascular events.

– Evaluation of digital decision support (AI ECG interpretation) to reduce false positives and unnecessary specialist referrals.

Conclusions

The 2025 German S2k consensus on Sports Preparticipation Evaluation for Healthy Adults offers a pragmatic, multidisciplinary approach centred on a comprehensive history and whole‑body examination. It emphasizes targeted use of ECG, imaging, stress testing and laboratory investigations—avoiding routine blanket testing—while insisting PPEs should generate individualized exercise prescriptions and behavior‑change support. The guideline balances population health goals (increasing safe activity) with the need to limit overtesting and resource waste.

For clinicians, the key actions are: use a standardized PPE form; compute validated cardiovascular risk from age 35; perform ECG and further cardiac imaging or stress testing only for indicated cases; refer musculoskeletal red flags promptly; and make the PPE a vehicle for credible, tailored exercise counseling.

Finally, the guideline’s authors recognize the current evidence gaps and call for registries and cohort studies to test whether a structured PPE reduces adverse events and improves long‑term health outcomes. Until such data exist, the consensus provides a reasoned, multidisciplinary framework for clinicians who help adults begin or resume active, and potentially health‑transforming, exercise.

References (selected)

– Joisten C, Hirschmüller A, Bauer P, et al. Sports Preparticipation Evaluation for Healthy Adults: A Consensus‑Based German Guideline. Sports Med. 2025;55(8):1827–1851. doi:10.1007/s40279-025-02230-5.

– Corrado D, Basso C, Pavei A, et al. Trends in sudden cardiovascular death in young competitive athletes after implementation of a preparticipation screening program. JAMA. 2006;296(13):1593–1601.

– American College of Sports Medicine. ACSM’s Guidelines for Exercise Testing and Prescription. 11th ed. 2021.

– SCORE2 Working Group/ESC Cardiovascular Risk Collaboration. SCORE2 algorithms to estimate 10‑year risk of cardiovascular disease in Europe. Eur Heart J. 2021;42(25):2439–2454.

– Harmon KG, Zigman M, Drezner JA. The effectiveness of screening history, physical exam, and ECG to detect potentially lethal cardiac disorders in athletes: a systematic review/meta‑analysis. J Electrocardiol. 2015;48(3):329–338.

– Schwellnus M, Swanevelder S, Derman W, et al. Prerace medical screening and education reduce medical encounters in distance road races (SAFER study). Br J Sports Med. 2019;53(10):634–639.

– Mont L, Pelliccia A, Sharma S, et al. Pre‑participation cardiovascular evaluation for athletic participants to prevent sudden death: EHRA/EACPR position paper. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2017;24(1):41–69.

– Piepoli MF, et al. 2016 European guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice. Eur Heart J. 2016;37(29):2315–2381.

– Kaminsky LA, Arena R, Myers J. Reference standards for cardiorespiratory fitness measured with CPET: FRIEND registry. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015;90(11):1515–1523.

(For a complete list of references cited in the guideline, see Joisten et al., Sports Med 2025.)