Highlight

– A confirmatory, double-blind, placebo-controlled multicenter RCT (n=160) tested simvastatin 40 mg daily added to escitalopram in adults with major depressive disorder (MDD) and obesity; no additional antidepressant effect was observed at 12 weeks (MADRS least squares mean difference 0.47 points; 95% CI, -2.08 to 3.02; P = .71).

– Simvastatin substantially improved cardiometabolic risk markers: LDL cholesterol down ≈40 mg/dL, total cholesterol down ≈39 mg/dL, and C-reactive protein decreased by about 1.0 mg/L versus placebo.

– The trial was well powered for a confirmatory test, achieved excellent retention (95.6%), and maintained blinding, strengthening the negative efficacy finding.

Study background and disease burden

Major depressive disorder (MDD) and obesity are prevalent, often co-occurring conditions that contribute substantially to global disability and cardiometabolic morbidity. Epidemiological meta-analyses indicate bidirectional associations between obesity and depression, with obesity increasing the future risk of depression and vice versa (Luppino et al., 2010). Mechanistic work has implicated low-grade systemic inflammation, metabolic dysregulation, and shared genetic pathways linking obesity and mood disorders. Elevated inflammatory markers, particularly C-reactive protein (CRP) and proinflammatory cytokines, have been reported in subsets of patients with MDD and have been proposed as potential treatment targets (Dowlati et al., 2010).

Statins—HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors—are widely prescribed for primary and secondary prevention of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Beyond lipid lowering, statins have pleiotropic anti-inflammatory and endothelial effects and some preclinical and small clinical studies suggested potential antidepressant properties. These observations led to the hypothesis that adjunctive statin therapy might augment antidepressant response in patients with MDD, particularly those with obesity and elevated cardiometabolic risk.

Study design

This confirmatory randomized clinical trial (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT04301271) enrolled adults with DSM-defined MDD and comorbid obesity across nine tertiary care centers in Germany. Key design elements:

– Design: Multicenter, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, parallel-group trial.

– Population: Adults with MDD and obesity; analytic intention-to-treat population included 160 participants (simvastatin n=81, placebo n=79); mean age 39.0 (SD 11.0) years; 79% female.

– Interventions: All participants received escitalopram 10 mg daily for the first 2 weeks, then 20 mg daily until week 12. Randomized add-on treatment was simvastatin 40 mg daily or matching placebo for 12 weeks.

– Primary outcome: Change in Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) from baseline to week 12.

– Secondary outcomes: Additional mental health–related scales, safety and tolerability outcomes, and cardiometabolic biomarkers including LDL cholesterol, total cholesterol, and CRP.

– Analysis: Mixed models for repeated measures in the intention-to-treat sample; pre-specified safety assessments and retention/blinding checks.

Key findings

Efficacy (primary outcome)

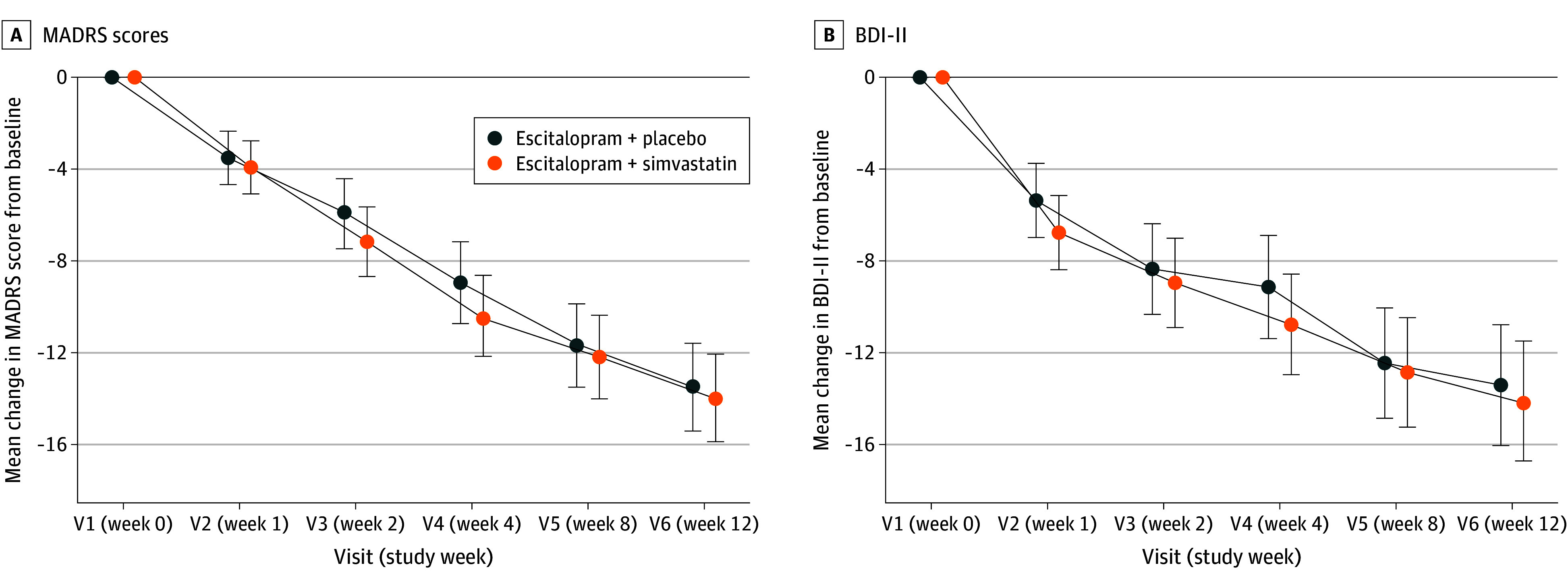

– Primary analysis showed no statistically significant benefit of add-on simvastatin on depressive symptoms measured by MADRS at 12 weeks: least squares mean difference 0.47 points favoring simvastatin (95% CI, -2.08 to 3.02; P = .71). This effect size is both statistically non-significant and clinically negligible.

– No significant effects were observed across mental health–related secondary endpoints. The negative result was consistent across intention-to-treat and sensitivity analyses reported.

Mean Change in Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) Scores Over 12 Weeks and Mean Change in Beck Depression Inventory II (BDI-II) Scores.

Safety and tolerability

– Retention was excellent (95.6%), indicating high adherence and feasibility of the protocol.

– Serious adverse events were uncommon (4 events total) with no difference between simvastatin and placebo groups, suggesting no short-term major safety signal for adjunctive simvastatin in this population.

Cardiometabolic and inflammatory biomarkers

– Simvastatin produced robust and expected lipid-lowering effects: LDL cholesterol decreased by a mean of ~40.4 mg/dL (95% CI, -47.41 to -33.33) in the simvastatin arm versus a small decrease in placebo (~ -3.78 mg/dL; 95% CI, -11.18 to 3.62; P < .001).

– Total cholesterol also declined markedly with simvastatin (mean change ≈ -39.1 mg/dL; 95% CI, -49.42 to -28.73) versus placebo (~ -4.9 mg/dL; 95% CI, -15.64 to 5.87; P < .001).

– Inflammation as measured by CRP decreased modestly but significantly with simvastatin (mean change -1.04 mg/L; 95% CI, -1.89 to -0.20) compared with an increase in the placebo group (mean change 0.57 mg/L; 95% CI, -0.28 to 1.42; P = .003).

Treatment Effects on Low-Density Lipoprotein (LDL) Cholesterol, Total Cholesterol, and C-Reactive Protein (CRP) Stratified by Visit and Treatment Group.

Interpretation of effect sizes and clinical meaning

– The trial was designed as a confirmatory test of efficacy; a near-zero mean difference on MADRS and wide CI encompassing clinically unimportant changes indicate a true lack of antidepressant effect of adjunctive simvastatin under the conditions tested.

– The clear improvements in LDL and total cholesterol confirm biological activity of the study drug and argue against pharmacologic failure as a reason for the negative mood result. The modest CRP reduction shows some anti-inflammatory action, though the magnitude may have been insufficient, or inflammation may not have been the primary driver of depressive symptoms in this sample.

Expert commentary

Strengths

– Rigorous randomized, double-blind design with prespecified confirmatory analysis improves confidence in the negative finding.

– Multicenter conduct and excellent retention reduce concerns about bias and enhance internal validity.

– Biomarker data demonstrate target engagement (lipid lowering and reduced CRP), providing mechanistic context.

Limitations and considerations

– Population characteristics: Mean age was relatively young (≈39 years) and predominantly female (79%), which may limit generalizability to older adults, men, or more severe/chronic MDD populations.

– Concomitant antidepressant treatment: All participants received escitalopram; thus the trial tested augmentation rather than statin monotherapy. A potential antidepressant effect of statins as monotherapy was not assessed.

– Duration: The exposure period was 12 weeks. Some hypothesized antidepressant effects mediated through neuroplastic or anti-inflammatory pathways might require longer treatment to manifest. Conversely, early signal would be expected if statins produced adjunctive symptomatic benefits within weeks.

– Baseline inflammation: The trial did not report that participants were selected for elevated inflammatory markers. Prior literature suggests that anti-inflammatory strategies may be most effective in depressed patients with elevated CRP or cytokines; lack of stratification may dilute potential benefit in an inflammatory subgroup.

– Statin choice and CNS penetration: Simvastatin is lipophilic and crosses the blood–brain barrier, which could be advantageous for central effects. However, differences among statins (lipophilicity, potency, off-target effects) mean negative results for simvastatin do not necessarily generalize to all statins.

Context with prior literature

– Earlier small RCTs and observational studies provided mixed signals about statins’ effects on mood, with some suggesting benefit. However, these were often underpowered, heterogeneous in design, and at risk of bias. The present well-powered negative trial provides a higher level of evidence against routine use of simvastatin as an antidepressant augmentation strategy in unselected obese patients with MDD.

Implications for practice and guidelines

– Clinicians should not prescribe statins specifically to treat depressive symptoms in patients with MDD on the basis of current evidence.

– For patients with comorbid obesity and elevated cardiovascular risk, statins remain indicated according to cardiology guidelines for primary prevention when appropriate; their cardiometabolic benefits are affirmed by this trial’s biomarker results, but mood improvement should not be expected as an ancillary benefit in the short term.

Future research directions

– Enrichment strategies: Trials selecting patients with elevated inflammatory biomarkers (e.g., CRP > 3 mg/L) could test whether inflammation-defined subgroups derive mood benefit from statins or other anti-inflammatory agents.

– Longer duration and different agents: Longer follow-up and testing other statins (hydrophilic vs lipophilic, differing potency) may clarify if any statin subtype or longer exposure yields antidepressant effects.

– Mechanistic studies: Parallel neuroimaging, peripheral and central immune profiling, and pharmacogenomic approaches could identify responders and clarify mechanisms of action.

Conclusion

This robust multicenter randomized trial demonstrates that adding simvastatin 40 mg daily to escitalopram does not confer additional antidepressant benefit over placebo in adults with MDD and obesity at 12 weeks, despite clear improvements in LDL, total cholesterol, and CRP. The findings argue against using simvastatin specifically as an augmenting antidepressant strategy in unselected obese patients with MDD. Future trials targeting inflammation-enriched patient subgroups, employing longer follow-up, or testing alternative agents or statin types may further refine whether and when anti-inflammatory or metabolic interventions can meaningfully improve depressive outcomes.

References

– Otte C, Chae WR, Dogan DY, et al. Simvastatin as Add-On Treatment to Escitalopram in Patients With Major Depression and Obesity: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2025 Aug 1;82(8):759-767. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2025.0801 IF: 17.1 Q1 . PMID: 40465256 IF: 17.1 Q1 ; PMCID: PMC12138799 IF: 17.1 Q1 .- Luppino FS, de Wit LM, Bouvy PF, et al. Overweight, obesity, and depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010 Mar;67(3):220-229. doi:10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.2 .- Dowlati Y, Herrmann N, Swardfager W, et al. A meta-analysis of cytokines in major depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2010 Mar 1;67(5):446-57. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.09.033 IF: 9.0 Q1 .- Ridker PM, Danielson E, Fonseca FA, et al.; JUPITER Study Group. Rosuvastatin to prevent vascular events in men and women with elevated C-reactive protein. N Engl J Med. 2008 Nov 20;359(21):2195-2207. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0807646 IF: 78.5 Q1 .