Highlights

– In a pooled prospective analysis of 18,935 hips from nine cohorts in the World COACH consortium, severe pincer morphology (LCEA ≥45°) was associated with higher odds of incident radiographic hip osteoarthritis (RHOA) within 8 years (OR 1.50, 95% CI 1.05–2.15).

– Moderate pincer morphology (LCEA ≥40°) was common (25.8% of hips) but not significantly associated with incident RHOA overall (OR 1.15, 95% CI 0.92–1.51).

– Subgroup signals suggested higher relative risk in younger middle-aged adults (40–50 years), people with BMI ≥25, and possibly women, indicating potential high-risk subgroups that merit targeted study.

Background

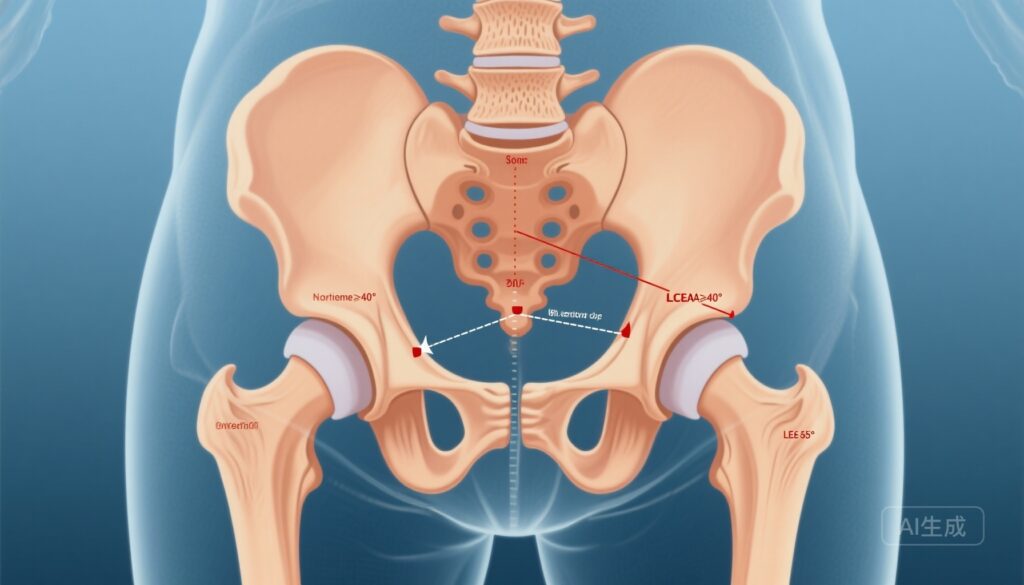

Femoroacetabular impingement (FAI) is a structural hip condition encompassing cam and pincer morphologies that can produce abnormal contact between the femoral head/neck and acetabulum. Pincer morphology refers to acetabular overcoverage of the femoral head and is commonly quantified on plain radiographs by the lateral centre edge angle (LCEA). Clinical and mechanistic studies have linked FAI to labral and cartilage injury and, in some cohorts, to increased risk of hip osteoarthritis (OA), but the role of isolated pincer morphology in the development of radiographic hip OA remains uncertain and heterogeneous across studies.

Study design and methods

Riedstra and colleagues pooled individual participant data from the World COACH consortium to examine prospectively whether baseline pincer morphology predicts incident radiographic hip osteoarthritis (RHOA) over 4–8 years of follow-up. Hips that were free of RHOA at baseline and had follow-up radiographs within the specified interval were included (n = 18,935 hips from nine cohorts).

Key elements:

- Exposure: Lateral centre edge angle (LCEA) measured uniformly on baseline anteroposterior pelvic radiographs. Moderate pincer defined as LCEA ≥40°; severe pincer was defined in sensitivity analyses as LCEA ≥45°.

- Primary outcome: Incident RHOA according to a harmonised osteoarthritis score applied across cohorts.

- Analysis: Multilevel logistic regression (generalised mixed effects) accounting for within-cohort, within-person, and within-side correlations, adjusted for age, biological sex, and body mass index (BMI).

- Follow-up: Mean 6.0 ± 1.7 years (maximum 8 years).

Key findings

Population characteristics: Of 18,935 hips included, 4,894 hips (25.8%) met the criterion for moderate pincer morphology (LCEA ≥40°). During follow-up, 352 hips (1.9%) developed incident RHOA.

Primary results

– Moderate pincer morphology (LCEA ≥40°): Not significantly associated with incident RHOA (adjusted OR 1.15, 95% CI 0.92–1.51). The absolute incidence of RHOA across the cohort was low (1.9% over mean 6 years), which constrains the potential population impact of modest relative effects.

– Severe pincer morphology (sensitivity analysis using LCEA ≥45°): Significantly associated with incident RHOA (adjusted OR 1.50, 95% CI 1.05–2.15). This suggests an effect threshold: greater acetabular overcoverage conveys higher odds of radiographic progression.

Subgroup and exploratory results

– Age: Hips in participants aged 40–50 years with moderate pincer morphology showed higher relative risk (RR 2.67, 95% CI 1.43–4.95) compared with non-pincer hips. This implies the association may be stronger in middle-aged adults where degenerative cascade may be emerging.

– BMI: Moderate pincer morphology in participants with BMI ≥25 had a higher point estimate for risk (RR 1.23, 95% CI 0.98–1.71), suggesting overweight may interact with structural overcoverage to increase risk.

– Sex: Women with pincer morphology had a numerically higher risk (RR 1.20, 95% CI 0.93–1.56) than men (RR 0.95, 95% CI 0.57–1.58), although confidence intervals overlapped and do not establish definitive sex differences.

Interpretation of effect size and clinical significance

The OR of 1.50 for severe pincer morphology reflects a modest increase in odds of developing radiographic changes compatible with hip OA within 8 years. Given the low overall absolute incidence (1.9%), the absolute risk increase attributable to severe pincer morphology over this time frame appears small. However, in identified subgroups (e.g., 40–50 years old), relative risks were larger, which may translate to clinically meaningful absolute differences in specific patient groups.

Expert commentary and context

These results help clarify a long-standing uncertainty in the FAI literature: while cam morphology has more consistently been implicated in incident hip OA in prospective studies, the relationship between pincer morphology and OA has been inconsistent. The World COACH pooled analysis strengthens evidence that degree of overcoverage matters: severe acetabular overcoverage (LCEA ≥45°) confers higher odds of RHOA, whereas more moderate degrees of overcoverage (LCEA ≥40°) do not show a consistent overall association.

Biomechanically, pronounced overcoverage can produce focal contact between the acetabular rim and femoral neck, potentially inducing labral compression and secondary cartilage damage. However, pincer morphology can also produce more global contact patterns and may in some settings cause less shear than cam lesions; this complex biomechanics likely contributes to heterogeneous clinical outcomes and makes threshold effects plausible.

Strengths of the study

- Large pooled individual participant dataset (18,935 hips) with standardised baseline LCEA measurement across cohorts.

- Prospective design with harmonised radiographic outcome definition and multilevel statistical modelling accounting for correlated data (within-person and within-cohort).

- Sensitivity and subgroup analyses that explored severity thresholds and effect modification by age, BMI, and sex.

Limitations and caveats

- Outcome measure is radiographic hip OA rather than symptomatic OA—radiographic change does not always parallel clinically meaningful pain or functional decline.

- Follow-up (mean 6 years) may be insufficient for full expression of OA resulting from structural abnormalities; longer-term outcomes could show different effect sizes.

- Plain radiographs and the LCEA metric have limitations: pelvic tilt and rotation, radiographic technique, and inter-reader variability can influence LCEA measurement. Cross-sectional imaging (CT, MRI) would provide more precise three-dimensional coverage measures.

- Residual confounding is possible despite adjustment for age, sex, and BMI. Activity level, previous hip injury, hip morphology elsewhere (cam lesions), and genetic factors were not fully accounted for in the presented summary.

- Although pooled, heterogeneity across cohorts (recruitment source, baseline risk) could affect generalisability to specific clinical populations.

Clinical implications and practical guidance

For clinicians evaluating incidental radiographic pincer morphology, the data suggest a nuanced approach:

- Moderate pincer morphology (LCEA ≥40° but <45°) appears common and, in this pooled analysis, not clearly associated with short- to mid-term development of RHOA overall. Routine aggressive intervention for asymptomatic moderate overcoverage is not supported solely by this association.

- Severe pincer morphology (LCEA ≥45°) is associated with higher odds of developing radiographic OA. In symptomatic patients with severe overcoverage, this finding may support more thorough evaluation and shared decision-making about interventions targeted at hip impingement when conservative measures fail.

- Consideration should be given to targeted surveillance or earlier conservative management measures (weight management, activity modification, physiotherapy) in individuals with pincer morphology who are middle-aged (40–50 years), have elevated BMI, or have symptoms, since subgroup analyses suggested higher relative risks in these groups.

- Decisions about FAI surgery should remain individualized, integrating symptoms, functional impairment, imaging correlates (including labral or cartilage damage on MRI), and patient priorities; the presence of pincer morphology alone—especially moderate degrees—should not be the sole indication for surgery in asymptomatic individuals.

Research and policy priorities

Key unanswered questions and directions:

- Longer-term prospective follow-up to determine whether moderate pincer morphology confers risk over decadal timescales and to examine progression to symptomatic OA and total hip replacement.

- High-quality imaging studies (CT, 3D MRI) to refine exposure measurement, explore dose–response relationships between acetabular coverage and cartilage injury, and integrate cam and pincer morphology analyses.

- Mechanistic studies linking focal cartilage and labral damage patterns to degrees of overcoverage and biomechanical loading, including activity-level interactions.

- Randomised or pragmatic trials comparing conservative versus surgical management in symptomatic patients with severe pincer morphology, with clinically meaningful outcomes (pain, function, progression to arthroplasty).

- Stratified analyses to identify and validate high-risk subgroups (age ranges, BMI thresholds, sex differences) for targeted prevention strategies.

Conclusion

The World COACH pooled individual-level analysis provides robust prospective evidence that severe pincer morphology (LCEA ≥45°) is associated with a modestly higher odds of incident radiographic hip osteoarthritis within 8 years, whereas moderate pincer (LCEA ≥40°) was not significantly associated overall. Absolute risk of radiographic change was low over the follow-up interval, but subgroup signals (middle-aged adults, higher BMI, women) point to potential patient groups who may warrant closer attention. Clinicians should integrate these findings with clinical symptoms, imaging of soft tissues, and patient preferences when making management decisions. Further research using longer follow-up, 3D imaging, and clinically relevant endpoints is needed to define which hips with acetabular overcoverage are most likely to progress and to guide optimal prevention and treatment strategies.

Funding and clinicaltrials.gov

Funding details and trial registrations are reported in the original article: Riedstra N et al., Br J Sports Med. 2025 Nov 4. Please consult the primary publication for specific funder acknowledgements and cohort registration information.

References

1. Riedstra N, Boel F, van Buuren MM, et al. Severe pincer morphology is associated with incident hip osteoarthritis: prospective individual participant data from 18 935 hips from the World COACH consortium. Br J Sports Med. 2025 Nov 4:bjsports-2024-109595. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2024-109595. PMID: 41192959.

2. Ganz R, Parvizi J, Beck M, Leunig M, Nötzli H, Siebenrock KA. Femoroacetabular impingement: a cause for osteoarthritis of the hip. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research. 2003;(417):112-120.

3. Beck M, Kalhor M, Leunig M, Ganz R. Hip morphology influences the pattern of damage to the acetabular cartilage: femoroacetabular impingement as a cause of early osteoarthritis of the hip. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research. 2005;(441):21-29.

Article provenance

This article synthesises and interprets findings from the cited World COACH consortium publication and places them in clinical and research context for practising clinicians and researchers.