Highlight

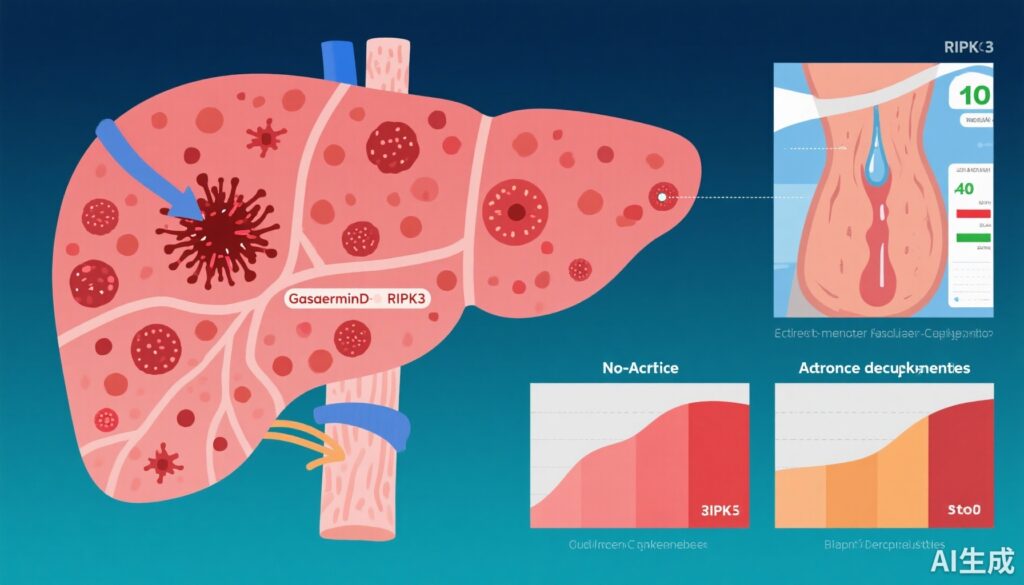

This study delineates non-acute decompensation (NAD) as a distinct clinical and pathophysiological stage in cirrhosis with intermediate survival outcomes between compensated cirrhosis and acute decompensation (AD). Patients with NAD demonstrate elevated markers of programmed cell death, notably Gasdermin-D and RIPK3, despite limited systemic inflammation. Key predictors of progression from NAD to AD include severe ascites, low serum IGF-1 and albumin, higher bilirubin, and enhanced cell death marker expression, suggesting potential therapeutic targets in necroptosis and pyroptosis pathways.

Background

Cirrhosis, a chronic liver disease culminating in liver failure, continues to pose significant morbidity and mortality worldwide. The clinical course is typically divided into compensated and decompensated stages, where the latter is associated with complications such as variceal hemorrhage, ascites, and hepatic encephalopathy. Acute decompensation (AD) episodes have been extensively studied due to their marked inflammatory response and poor prognosis. However, a less characterized intermediate state termed non-acute decompensation (NAD) has been identified, exhibiting heterogenous clinical presentations and prognosis. Understanding NAD’s clinical and pathophysiological landscape is critical for improved risk stratification and early intervention strategies to prevent transition to AD and subsequent mortality.

Study Design and Methods

This prospective multicenter cohort study was conducted in two tertiary centers in India between 2020 and 2023. The study enrolled 551 participants categorized into four groups: compensated cirrhosis (CC, n=29), non-acute decompensation (NAD, n=311), acute decompensation (AD, n=201), and healthy controls (n=10). Baseline clinical assessments included severity of ascites, body mass index (BMI), Child-Turcotte-Pugh (CTP) and Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) scores. Laboratory evaluations encompassed liver function tests, serum levels of inflammatory cytokines (IL-6, TNF, IL-10, MCP-1), and programmed cell death markers (M30, M65, Gasdermin-D, RIPK3, MLKL). Twelve-month follow-up assessed overall survival and monitored progression from NAD to AD. Statistical analyses identified predictors of disease progression and mortality within the NAD group.

Key Findings

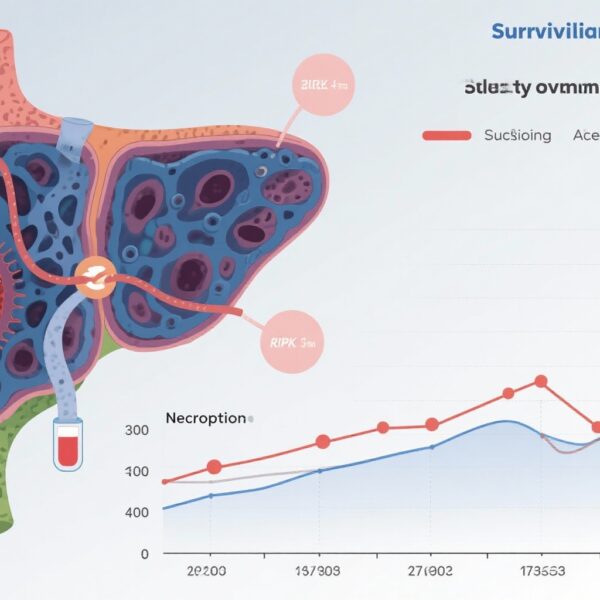

Survival Outcomes: Survival at 12 months was significantly different across groups: 100% in CC, intermediate 81.7% in NAD, and poorest in AD at 31.2% (p < 0.001). Patients with NAD therefore represent a subgroup with substantial risk but better outcomes than AD.

Inflammatory and Cell Death Profiles: Unlike AD, NAD patients did not show significant systemic inflammation; cytokine levels (IL-6, TNF, IL-10, MCP-1) were not markedly elevated compared to controls or CC. However, NAD exhibited elevated cell death markers Gasdermin-D and RIPK3 relative to healthy controls and CC, indicating activation of programmed necroptosis and pyroptosis pathways even in absence of florid inflammation. The highest levels of both inflammatory and cell death markers were observed in AD patients, reflecting acute liver injury and systemic inflammatory response.

Predictors of Progression and Mortality in NAD: Over 12 months, 55.1% of NAD patients progressed to AD, markedly reducing survival (68.2% vs 95.3%, p < 0.001). Multivariate predictors for progression included:

- Severe ascites (clinically significant fluid accumulation)

- Lower serum insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) and albumin levels

- Higher total bilirubin levels

- Elevated Gasdermin-D and RIPK3 concentrations

- Higher CTP and MELD scores

- Lower BMI

These factors depict deteriorating liver synthetic function, nutritional status, and activation of cell death pathways as key elements driving clinical worsening.

Expert Commentary

This robust prospective study clarifies the heterogeneous spectrum of cirrhosis decompensation by characterizing NAD as a distinct entity from both compensated and acutely decompensated stages. The absence of marked systemic inflammation in NAD challenges paradigms that inflammation is the sole driver of decompensation and implicates programmed cell death mechanisms, such as necroptosis and pyroptosis, in disease progression. Clinical predictors such as ascites severity and conventional scores remain essential, while emerging biomarkers like Gasdermin-D and RIPK3 offer novel prognostic insight and therapeutic targets.

The identification of necroptosis and pyroptosis pathways opens promising avenues for disease-modifying interventions. Research into inhibitors targeting these pathways could prevent NAD progression, reduce healthcare burden, and improve transplant candidacy. Nevertheless, the study’s limitations include its geographic concentration in Indian centers, which may affect generalizability, and potential confounding variables inherent in observational design. Future studies should validate findings across diverse populations and explore interventional trials targeting cell death modulation.

Conclusion

Non-acute decompensation in cirrhosis constitutes a clinically and pathophysiologically unique stage marked by elevated programmed cell death despite limited systemic inflammation. NAD patients have significant risk of progression to acute decompensation and mortality, highlighting the need for enhanced risk stratification using combined clinical parameters and novel biomarkers such as Gasdermin-D and RIPK3. Targeting necroptosis and pyroptosis represents a novel therapeutic frontier in cirrhosis management, potentially shifting the paradigm towards precision medicine. This study underscores the importance of recognizing NAD to optimize timing for intervention and improve patient outcomes.

Funding and ClinicalTrials.gov

The study was conducted without reported external funding. Clinical trial registrations were not stated within the publication.

References

Verma N, Kaur P, Garg P, Ranjan V, Ralmilay S, Rathi S, De A, Premkumar M, Taneja S, Roy A, Goenka M, Duseja A, Jalan R. Clinical and pathophysiological characteristics of non-acute decompensation of cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 2025 Sep;83(3):670-681. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2025.02.028. Epub 2025 Mar 7. Erratum in: J Hepatol. 2025 Sep 25:S0168-8278(25)02475-4. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2025.09.001. PMID: 40056937.