Highlights

• In the KIWE open-label randomised trial (n=136), a classic ketogenic diet was not superior to an additional antiseizure medication for reducing seizure frequency in infants with drug‑resistant epilepsy at 8 weeks (IRR 1.33, 95% CI 0.84–2.11).

• Responder rates (≥50% seizure reduction) and seizure‑freedom rates were similar between groups (44% vs 40% responders; 11% vs 13% seizure‑free).

• Serious adverse events occurred in similar proportions (51% ketogenic diet vs 45% antiseizure medication); three deaths occurred in the ketogenic diet arm but were judged unrelated to treatment.

• The trial supports the ketogenic diet as a safe and tolerable alternative to further pharmacotherapy in infants who have failed two antiseizure medicines, while highlighting limitations that temper definitive conclusions.

Study background and disease burden

Epilepsy incidence peaks in the first 2 years of life, and infant‑onset epilepsies frequently have high seizure burden and risk of adverse neurodevelopmental outcome. Early seizure control is associated with improved developmental trajectories, but many infantile epilepsy syndromes are pharmacoresistant. Non‑pharmacologic therapies, notably ketogenic dietary therapies, have an established role in older children and adults with drug‑resistant epilepsy, but evidence in infants has been limited and mainly uncontrolled. The KIWE (Ketogenic diet In the treatment of epilepsy in infants With drug-resistant Epilepsy) trial was designed to provide high‑quality comparative data on the classic ketogenic diet versus further antiseizure medication in infants with persistent frequent seizures despite two or more prior antiseizure treatments.

Study design

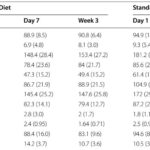

KIWE was a phase 4, multicentre, open‑label randomised clinical trial conducted across 19 UK hospitals. Eligibility included infants aged 1–24 months with drug‑resistant epilepsy defined pragmatically as ≥4 seizures per week and failure of at least two prior antiseizure medications (including steroids). After a 1–2 week baseline observation, participants were randomised (simple randomisation, no stratification) to either a classic ketogenic diet (initiated non‑fasting at ratios usually 2:1–4:1 fat:(protein+carbohydrate), with dietitian oversight and monitoring) or to an additional antiseizure medication selected by the treating clinician according to syndrome and prior treatments. The primary endpoint was the median number of seizures/day during weeks 6–8, adjusted for baseline seizure rate. Key secondary outcomes included ≥50% responder rate, seizure freedom during weeks 6–8, tolerability, laboratory safety markers, and medium‑chain fatty acid concentrations. Participants were followed up to 12 months; the trial was terminated early due to slow recruitment and funding constraints.

Key findings

Population and follow‑up: Of 155 infants screened, 136 were randomised (78 to ketogenic diet, 58 to antiseizure medication). Modified intention‑to‑treat analyses included 61 in the ketogenic diet group and 47 in the antiseizure medication group with primary outcome data at 8 weeks. Median follow‑up was 11.3 months but data completeness declined at 12 months.

Primary outcome: During weeks 6–8, median seizures/day were 5 (IQR 1–16) for the ketogenic diet group versus 3 (IQR 2–11) for the antiseizure medication group. The incidence rate ratio (IRR) adjusted for baseline and centre was 1.33 (95% CI 0.84–2.11), indicating no statistically significant difference and no evidence of superiority of the diet in this cohort.

Secondary seizure outcomes: Responder rates (≥50% reduction) were 44% (28/63) for ketogenic diet and 40% (19/47) for antiseizure medication (OR 1.21, 95% CI 0.55–2.65). Seizure freedom at 8 weeks occurred in 11% (7/63) versus 13% (6/48) respectively (OR 0.88, 95% CI 0.27–2.80). These point estimates are numerically similar between arms and consistent with prior reports of ketogenic diet responder rates in infants (~40–60%) and older children.

Safety and tolerability: The proportion of infants experiencing at least one serious adverse event (SAE) was comparable: 51% (40/78) in the ketogenic diet arm and 45% (26/58) in the antiseizure medication arm. Seizure exacerbations and infections were common SAEs. Three deaths occurred among infants randomised to the ketogenic diet; each was adjudicated as unrelated to the intervention by investigators and the data safety monitoring committee. Laboratory changes consistent with ketosis (e.g., increased β‑hydroxybutyrate), and expected alterations in lipids and carnitine profiles, were observed in the diet group but without clinically significant laboratory derangements overall.

Retention and crossover: Retention at 12 months was modest and affected by early trial termination; among participants with the opportunity for 12‑month follow‑up, ~64% remained on the ketogenic diet and ~67% on antiseizure medication. Notably, more participants assigned to antiseizure medication required changes to concurrent antiseizure regimens during the trial, and more in that group subsequently switched to a ketogenic diet outside the trial at 8 weeks.

Interpreting the results: effect size, precision, and clinical meaning

The KIWE trial was designed as a superiority study and, after sample size recalculation, had 80% power to detect the prespecified effect; however, recruitment stopped short of the original target and the trial ended early, limiting precision. The adjusted IRR for seizure frequency (1.33, 95% CI 0.84–2.11) crosses the null and cannot exclude a modest benefit or harm. Secondary outcomes (responder and seizure‑freedom rates) produced overlapping confidence intervals and no significant differences. Clinically, the data indicate that the ketogenic diet performed broadly comparably to clinician‑selected additional antiseizure medication in this heterogeneous, high‑risk infant population over an 8‑week primary assessment window.

Expert commentary and mechanistic considerations

These findings align with prior randomized data in older children showing improved seizure control with ketogenic diets compared with usual care, while adding a head‑to‑head comparison with pharmacotherapy in infants. Mechanistically, medium‑chain fatty acids (notably decanoic acid) have been implicated in antiseizure effects and mitochondrial modulation, and infants may metabolically adapt to fat oxidation more readily than older children. The trial attempted measurement of medium‑chain fatty acids, but logistical sample stability issues limited meaningful analysis—an important area for future biomarker work.

Limitations to weigh: open‑label design may introduce expectation bias; non‑stratified randomisation could allow imbalance (although baseline characteristics were broadly similar); heterogeneous epilepsy etiologies reduce ability to detect syndrome‑specific effects; the 8‑week primary window is shorter than some adult/older‑child trials and may miss later responses to diet; early termination with incomplete 12‑month data reduced power for longer‑term outcomes and neurodevelopmental measures.

Clinical implications

For clinicians managing infants with persistent seizures after two antiseizure medications, KIWE suggests the classic ketogenic diet is a reasonable, evidence‑supported option with comparable short‑term efficacy and tolerability to trying another antiseizure medication. Practical considerations remain: careful metabolic screening to exclude contraindications, structured dietitian input for initiation and monitoring, parental education and support, and monitoring for potential metabolic or nutritional abnormalities. The choice between initiating dietary therapy versus another drug should be individualized, considering epilepsy syndrome, prior drug history, family preferences, logistics of diet implementation, and access to dietetic services.

Research and policy priorities

Future trials should consider: adaptive or syndrome‑stratified designs; longer primary assessment windows to capture delayed diet response; biomarkers (including medium‑chain fatty acids) to predict responders; and pragmatic approaches to reduce recruitment barriers in acutely ill infants. Policy‑wise, KIWE underscores the need for accessible ketogenic diet services and trained dietitians for infants within health systems so families can realistically choose diet therapy when appropriate.

Conclusion

The KIWE trial provides the first randomised evidence comparing the classic ketogenic diet with further antiseizure medication in infants with drug‑resistant epilepsy. It did not demonstrate superiority of the diet but found broadly similar efficacy, safety, and tolerability over an 8‑week assessment period. The ketogenic diet can therefore be presented as an evidence‑based treatment option for infants after failure of two antiseizure drugs, with shared decision‑making that incorporates clinical context, resource considerations, and family preference. Larger, longer, and syndrome‑targeted studies are needed to refine patient selection and optimise treatment sequencing.

References

1. Schoeler NE, Marston L, Lyons L, et al. Classic ketogenic diet versus further antiseizure medicine in infants with drug‑resistant epilepsy (KIWE): a UK, multicentre, open‑label, randomised clinical trial. Lancet Neurol. 2023;22:1113–24.

2. Martin‑McGill KJ, Bresnahan R, Levy RG, Cooper PN. Ketogenic diets for drug‑resistant epilepsy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;6:CD001903.

3. Neal EG, Chaffe H, Schwartz R, et al. The ketogenic diet for the treatment of childhood epilepsy: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 2008;7:500–6.

4. Lyons L, Schoeler NE, Langan D, Cross JH. Use of ketogenic diet therapy in infants with epilepsy: A systematic review and meta‑analysis. Epilepsia. 2020;61:1261–81.

5. van der Louw EJTM, van den Hurk D, Neal E, et al. Ketogenic diet guidelines for infants with refractory epilepsy. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2016;20:798–809.

6. Dressler A, Benninger F, Trimmel‑Schwahofer P, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of the ketogenic diet versus high‑dose adrenocorticotropic hormone for infantile spasms: a single‑center parallel‑cohort randomized controlled trial. Epilepsia. 2019;60:441–51.

7. Auvin S, French J, Dlugos D, et al. Novel study design to assess efficacy and tolerability of antiseizure medications for focal‑onset seizures in infants and young children: consensus document. Epilepsia Open. 2019;4:537–43.