Study Background and Disease Burden

Ischemic stroke remains a leading cause of long-term disability worldwide, with substantial physical, cognitive, and emotional sequelae. Beyond traditional motor and sensory impairments, many stroke survivors face invisible challenges such as cognitive deficits, anxiety, depression, and limited societal participation, all of which critically affect quality of life (QoL). Despite awareness of these issues, current evidence guiding systematic screening and management of post-stroke emotional and cognitive problems is limited. There remains an unmet clinical need to determine whether structured screening and intervention can effectively enhance rehabilitation outcomes, especially societal re-engagement after ischemic stroke in patients not receiving inpatient or outpatient rehabilitation services.

Study Design

This investigation was a multicenter, patient-masked, cluster-randomized controlled trial conducted across 12 Dutch nonuniversity hospitals equipped with stroke units. Clusters (hospitals) were randomized 1:1 to either an intervention arm or usual care. Eligible participants were adults (≥18 years) recovering from ischemic stroke and discharged home without referral to inpatient or outpatient rehabilitation.

The intervention comprised a specialized stroke nurse-led consultation at 6 weeks post-stroke during outpatient neurology visits. This consultation included comprehensive screening for emotional and cognitive problems, assessment of participation restrictions using standardized tools, and tailored self-management support. Patients identified with significant issues were referred to appropriate rehabilitation services. Usual care clusters continued standard follow-up without this structured intervention.

The trial’s primary endpoint was societal participation measured by the Restrictions subscale of the Utrecht Scale for Evaluation of Rehabilitation-Participation (USER-P-R) at 1 year after stroke. Secondary outcomes evaluated at 3 and 12 months included cognitive and emotional concerns (Checklist for Cognitive and Emotional Consequences following Stroke), symptoms of anxiety and depression (Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale – anxiety and depression subscales), various QoL metrics (EQ-5D-5L index, EQ-VAS, and PROMIS-10), self-efficacy (General Self-Efficacy Scale), and disability (modified Rankin Scale). Data analysis used mixed models for repeated measures and ordinal mixed-effects models.

Key Findings

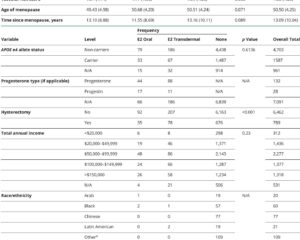

Between August 2019 and May 2022, 531 patients across 12 hospitals were enrolled—264 in intervention and 267 in usual care clusters. The cohort had a mean age of 70.6 years (±9.7), with 40% female participants and mild stroke severity (median NIH Stroke Scale = 2).

Primary analysis revealed no statistically significant or clinically meaningful difference in societal participation at 1 year: the USER-P-R mean difference was 0.77 (95% confidence interval [CI] -2.46 to 4.06; p=0.652). This indicates that the structured screening and care consultation did not improve overall societal engagement or participation restrictions compared to usual care.

Nonetheless, secondary outcomes showed modest early benefits at 3 months:

– Anxiety symptoms (HADS-A) were reduced by a mean of -0.86 points (95% CI -1.33 to -0.39) in the intervention group relative to controls.

– Quality of life measured by EQ-5D-5L improved by 0.044 points (95% CI 0.022 to 0.065).

– EQ-VAS scores increased by 2.90 points (95% CI 0.69 to 5.10).

At 1 year, EQ-5D-5L index scores remained slightly higher in the intervention group by 0.043 points (95% CI 0.021 to 0.064), reflecting a sustained but modest QoL benefit.

Other secondary outcomes, including depression symptoms, cognitive concerns, self-efficacy, and disability scores, did not show significant differences between groups at either time point.

Expert Commentary

This rigorously conducted cluster-randomized trial provides important insights into post-stroke care paradigms. The lack of improvement in the primary endpoint suggests that a single nurse-led screening and consultation visit at 6 weeks may be insufficient to translate into meaningful gains in societal participation by one year. This may be due to multiple factors including low baseline disability, the modest dose of the intervention, or the delayed timing of screening.

The early reduction in anxiety symptoms and improved QoL metrics are encouraging, suggesting that emotional and cognitive screening and subsequent support could have short-term psycho-social benefits. These findings align with the mechanistic understanding that anxiety and mood disorders interact with recovery trajectories post-stroke and impact patient-perceived health.

Several limitations merit consideration. First, the study cohort represented patients discharged home without rehabilitation, limiting generalizability to those with more severe deficits requiring rehabilitation. Second, the intervention’s intensity and frequency were limited; more sustained or multidisciplinary approaches might yield greater impact. Third, the study did not assess the cost-effectiveness at this stage, which is critical for implementation decisions.

These results underscore ongoing debates in stroke neurorehabilitation regarding the optimal timing, scope, and personnel for screening and intervention. Future research may explore integrating such screening into broader, multidisciplinary follow-up, leveraging telehealth, or targeting higher-risk patients. Current guidelines acknowledge the high prevalence of neuropsychiatric and cognitive difficulties after stroke, but evidence for routine systematic screening and intervention remains equivocal.

Conclusion

In conclusion, active screening and care for emotional and cognitive problems at 6 weeks post-ischemic stroke did not improve societal participation at 1 year in patients discharged home without rehabilitation. However, this approach demonstrated small but statistically significant improvements in short-term anxiety symptoms and quality of life. These findings advocate for further investigation into tailored, possibly more intensive interventions to address the complex emotional and cognitive needs of stroke survivors. Ongoing economic evaluations will inform the cost-benefit balance of such programs. Clinicians should continue to monitor emotional and cognitive complications and consider individualized supportive strategies while evidence evolves.

References

Slenders JPL, Van Den Berg-Vos RM, Van Heugten CM, Visser-Meily J, van Eijk RPA, Moonen MAA, Godefrooij S, Kwa VIH; ECO-stroke Study Group. Screening and Care for Emotional and Cognitive Problems After Ischemic Stroke: Results of a Multicenter, Cluster-Randomized Controlled Trial. Neurology. 2025 Jul 8;105(1):e213774. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000213774.

Hilari K, Northcott S, Roy P, Marshall J. Emotional and cognitive problems after stroke: challenges to recovery and quality of life. Top Stroke Rehabil. 2019;26(7):491-498.

Cumming TB, Marshall RS, Lazar RM. Stroke, cognitive deficits, and rehabilitation: still an incomplete picture. Int J Stroke. 2013;8(1):38-45.

Hackett ML, Pickles K. Part I: Frequency of Depression After Stroke: An Updated Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Observational Studies. Int J Stroke. 2014;9(8):1017-1025.