Highlight

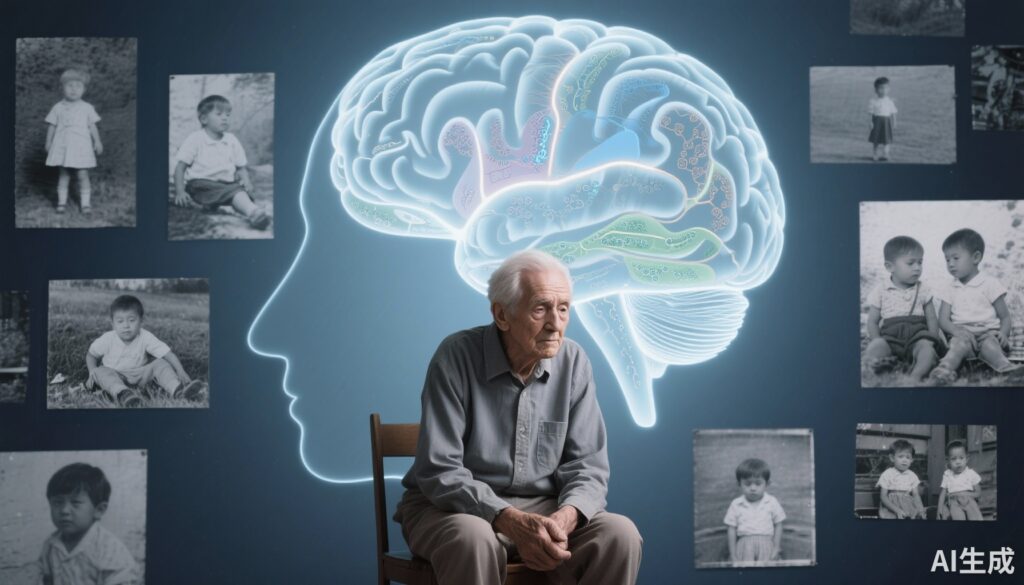

- Childhood loneliness is associated with accelerated cognitive decline in middle-aged and older adults.

- Experiencing loneliness in childhood increases dementia risk independently of adult loneliness.

- Adult loneliness partly mediates, but does not significantly alter, the impact of childhood loneliness on cognitive outcomes.

- Early interventions addressing childhood loneliness could be crucial for lifelong cognitive health.

Study Background and Disease Burden

Loneliness, both as a subjective feeling of social isolation and as an objective state of lack of social connections, has emerged as a critical public health concern linked to adverse mental and physical health outcomes. While the deleterious effects of loneliness in adulthood, particularly among older adults, have been extensively studied—indicating increased risks of cognitive deterioration and dementia—the role of loneliness originating earlier in life, during childhood, remains poorly understood. With dementia prevalence expected to escalate worldwide due to aging populations, identifying modifiable risk factors across the lifespan is imperative. This study addresses a significant gap by exploring the long-term cognitive consequences of childhood experiences of loneliness, a potentially preventable psychosocial adversary, thereby expanding the framework for dementia risk reduction strategies.

Study Design

This prospective cohort analysis utilized data from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS), a nationally representative cohort initiated in 2011. Participants included 13,592 adults aged approximately 58 years on average, monitored over a maximum follow-up period of seven years until 2018. Childhood loneliness was ascertained retrospectively through self-reports of frequent loneliness and absence of close friendships before age 17. Adult loneliness status was measured via a validated single item from the Centre for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale during the study period.

Cognitive outcomes were assessed longitudinally with established tests evaluating episodic memory and executive function, while dementia diagnosis involved a composite measure of cognitive impairment plus functional disability or self-/caregiver-reported physician diagnosis. Analytical methods comprised linear mixed-effects models to assess cognitive decline trajectories and Cox proportional hazards models to evaluate dementia risk, adjusting for pertinent confounders including adult loneliness.

Key Findings

Among participants, 48.0% reported possible childhood loneliness and 4.2% definite childhood loneliness. Both possible and definite childhood loneliness were significantly linked with faster rates of cognitive decline: .0% and .0% standard deviation (SD) per year, respectively. The hazard ratio for developing dementia was 1.41 (95% CI, 1.03 to 1.93) in those reporting childhood loneliness compared to those without.

Importantly, these associations persisted even after adjusting for adult loneliness and when analyses were restricted to participants without adult loneliness, indicating an independent effect of childhood loneliness on later-life cognition. Mediation analysis revealed that adult loneliness accounted for only a modest proportion of these associations—8.5% (95% CI, 2.9% to 14.1%) for cognitive decline and 17.2% (95% CI, 4.9% to 29.5%) for dementia risk—but did not modify the strength of associations significantly.

These findings underscore the lasting influence of early-life social-emotional adversity on brain health trajectories extending into middle and later adulthood.

Expert Commentary

This robust longitudinal investigation confirms and extends prior evidence linking loneliness with adverse cognitive outcomes. From a mechanistic perspective, childhood loneliness may engender chronic stress responses, neuroinflammation, and altered neurodevelopmental processes, leaving a neural substrate more vulnerable to aging-related decline. The study’s control for adult loneliness strengthens the argument that childhood experiences cannot be simply explained away by adult psychosocial status.

Limitations include reliance on retrospective reporting of childhood loneliness, which may be subject to recall bias, and generalizability predominantly to East Asian populations, necessitating replication in diverse cohorts. Moreover, although associations are compelling, causal inferences demand cautious interpretation given observational design.

Contemporary clinical guidelines have yet to integrate childhood psychosocial factors in dementia risk assessments. This study advocates for early-life social health as a critical domain for intervention, highlighting potential benefits of family-, school-, and community-based programs aimed at fostering social connectivity and emotional support during childhood.

Conclusion

The association of childhood loneliness with accelerated cognitive decline and elevated dementia risk in adulthood—even when adult loneliness is absent—emphasizes the enduring impact of early social experiences on brain aging. Public health strategies targeting childhood social isolation and loneliness hold promise in mitigating dementia burden. Future research should explore targeted interventions in childhood, longitudinal neurobiological pathways linking loneliness and neurodegeneration, and cross-cultural validation to inform comprehensive lifelong cognitive health promotion.

References

1. Wang J, Jiao D, Zhao X, et al. Childhood Loneliness and Cognitive Decline and Dementia Risk in Middle-Aged and Older Adults. JAMA Netw Open. 2025;8(9):e2531493. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2025.31493

2. Cacioppo JT, Cacioppo S. Loneliness in the modern age: an evolutionary theory of loneliness (ETL). Adv Exp Soc Psychol. 2018;58:127-197.

3. Holwerda TJ, Deeg DJH, Beekman ATF, et al. Increased Risk of Mortality Associated With Social Isolation in Older Adults: Study of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(12):1512-1520. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.2135

4. Hawkley LC, Cacioppo JT. Loneliness matters: a theoretical and empirical review of consequences and mechanisms. Ann Behav Med. 2010;40(2):218-227.

5. Wilson RS, Krueger KR, Arnold SE, et al. Loneliness and risk of Alzheimer disease. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64(2):234-240. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.2.234