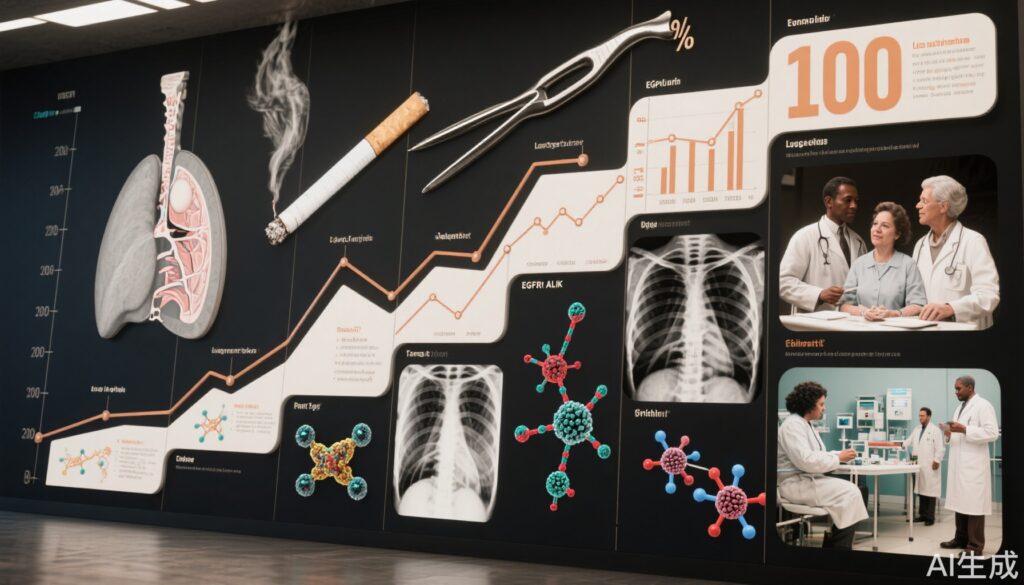

Highlights

- Lung cancer transitioned from a clinical rarity to the world’s leading cause of cancer death, in part due to changes in smoking habits and advances in diagnostic technology.

- Therapeutic breakthroughs—from surgery to molecularly targeted agents and immunotherapies—have significantly improved survival in certain subtypes, especially non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC).

- Precision medicine now enables treatment tailored to genetic drivers like EGFR, ALK, ROS1, BRAF, RET, MET, and KRAS, as well as immune checkpoint inhibition and antibody-drug conjugates.

- Despite progress, late-stage diagnosis and drug resistance remain key challenges, highlighting the need for continued innovation and early detection.

Background and Disease Burden

Lung cancer remains the most prevalent and deadliest cancer worldwide. According to the 2024 GLOBOCAN report, approximately 1.8 million people die annually from lung cancer—about ten every three minutes. Yet, over a century ago, lung cancer was considered exceedingly rare. In 1912, a New York physician could find only 374 documented cases worldwide. This rarity was likely due to both genuine low incidence and significant underdiagnosis; the absence of modern diagnostic tools meant many cases were mistaken for tuberculosis and only discovered at autopsy. By the late 1940s, however, lung cancer incidence exploded, closely paralleling the rise in cigarette smoking and improved diagnostic awareness.

Uncovering the Culprit: Smoking and Lung Cancer

A pivotal moment in lung cancer research came in 1950 with the publication by Richard Doll and Austin Bradford Hill, who demonstrated a dramatic 14-fold increase in lung cancer mortality in England and Wales between 1922 and 1947. By systematically comparing lung cancer patients with other cancer controls in London hospitals, they identified a strong association with tobacco use, a finding rapidly confirmed by subsequent studies. Landmark reports from the Royal Society of Medicine (UK) and the U.S. Surgeon General in the 1960s established smoking as the major preventable cause of lung cancer. Following these reports, smoking rates—and, two decades later, lung cancer incidence—began to decline in several countries, highlighting the critical impact of public health interventions.

The “Dark Age”: Limited Progress in Therapy

Despite gains in epidemiological understanding and diagnosis, therapeutic advances for lung cancer lagged. Surgery was the mainstay for early-stage disease, offering reasonable outcomes if the tumor was localized and resectable. However, most patients presented with advanced disease, often beyond the reach of surgical cure. For these cases, radiotherapy, radiofrequency ablation, and cytotoxic chemotherapy offered modest benefits at the cost of significant toxicity, as their mechanisms attacked both cancerous and healthy cells indiscriminately. Five-year survival rates for advanced lung cancer remained dismally low throughout the late 20th century, prompting a sense of therapeutic pessimism.

The Rise of Molecular Targeted Therapy: EGFR as a Paradigm

The turn of the millennium ushered in a molecular era. Advances in cancer biology revealed that approximately 85% of lung cancers are non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), with frequent alterations in genes like EGFR (epidermal growth factor receptor). EGFR overexpression or mutation—present in up to a third of NSCLC patients—drives uncontrolled cell growth. The first-generation EGFR inhibitors (gefitinib, erlotinib, icotinib) marked the inception of targeted therapy. However, initial clinical trials yielded mixed results, illuminating the importance of molecular stratification; benefits were mostly confined to patients with specific EGFR mutations.

Second-generation (afatinib, dacomitinib) and third-generation (osimertinib, lazertinib, mobocertinib, sunvozertinib) EGFR inhibitors improved on these outcomes, overcoming some resistance mechanisms such as the T790M mutation. For example, osimertinib doubled median progression-free survival (PFS) compared to first-generation agents. These advances transformed the prognosis for many patients with EGFR-mutant NSCLC.

Expanding the Molecular Arsenal: ALK, ROS1, BRAF, RET, MET, and KRAS

Subsequent research uncovered additional actionable targets:

- ALK rearrangements (~5% of NSCLC), often in non-smokers, led to successive generations of ALK inhibitors (crizotinib, ceritinib, alectinib, brigatinib, lorlatinib, ensartinib) with increasing efficacy and central nervous system penetration.

- ROS1, BRAF V600E, RET, and MET mutations/fusions have similarly yielded new classes of inhibitors (entrectinib, repotrectinib, dabrafenib/trametinib, selpercatinib, pralsetinib, tepotinib, capmatinib, and others), each offering significant clinical benefit in their niche populations.

- KRAS, once considered “undruggable,” is now targetable with G12C-specific inhibitors (sotorasib, adagrasib, and others), approved since 2021–22, offering new hope for up to 13% of NSCLC patients.

Immunotherapy: A Paradigm Shift

The introduction of immune checkpoint inhibitors—nivolumab, pembrolizumab, atezolizumab, durvalumab, and others—has redefined the therapeutic landscape for advanced NSCLC. Previously, five-year survival for metastatic NSCLC was just 5.5%; immunotherapy has tripled this figure to approximately 18% in selected patients. These therapies work by unleashing the patient’s own immune system against the tumor, and are now approved in both monotherapy and combination regimens, with ongoing research into biomarkers to optimize patient selection.

Antibody-Drug Conjugates and Bispecific Antibodies: The Next Frontier

Beyond small molecules and monoclonal antibodies, innovative modalities like antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs) and bispecific antibodies have entered clinical practice. Examples include trastuzumab deruxtecan (Enhertu) for HER2-mutant NSCLC, telisotuzumab vedotin for MET, and datopotamab deruxtecan for TROP2. Bispecifics such as amivantamab (EGFR/MET), zenocutuzumab (HER2/HER3), and ivonescimab (PD-1/VEGF) offer multi-targeting potential.

Expert Commentary and Mechanistic Insights

The evolution of lung cancer therapy exemplifies the paradigm shift from non-specific cytotoxicity to precision medicine. As Dr. Spiro and Dr. Silvestri (2005) aptly noted, the last century has seen lung cancer move from obscurity to the center of oncology research. While advances in diagnostics, risk reduction (notably smoking cessation), and therapeutic innovation have dramatically improved outcomes for molecularly defined subgroups, challenges remain. Drug resistance, intratumoral heterogeneity, and limited survival gains in certain populations underscore the need for ongoing research, early detection, and multidisciplinary care.

Conclusion

The past 100 years have witnessed a revolution in lung cancer management. From a rare and poorly understood entity, lung cancer is now at the forefront of precision oncology, thanks to advances in molecular profiling, targeted therapy, and immunotherapy. These changes have translated into tangible survival benefits for many, though continued efforts are needed to address drug resistance and improve early detection. The trajectory of lung cancer care demonstrates the power of translational research and public health policy in changing the course of a disease once deemed untreatable.

References

- Spiro, S.G., & Silvestri, G.A. (2005). One Hundred Years of Lung Cancer. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, 172(5), 523-529. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.200504-531OE

- GLOBOCAN 2024. Global Cancer Observatory: Cancer Today. International Agency for Research on Cancer. https://gco.iarc.fr/today

- Doll, R., & Hill, A.B. (1950). Smoking and carcinoma of the lung; preliminary report. British Medical Journal, 2(4682), 739-748.

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) Guidelines: Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. (2024).

- Herbst, R.S. et al. (2018). Pembrolizumab versus Docetaxel for Previously Treated, PD-L1-Positive, Advanced Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. New England Journal of Medicine, 375, 1823-1833.