Introduction and Context

Gastric cancer remains a leading cause of cancer death worldwide, concentrated in East Asia, parts of South America and Central Asia. In 2025 the Second Taipei Global Consensus (Gut 2025; Liou et al.) revisited whether—and how—screening for and eradicating Helicobacter pylori should be used as a primary prevention strategy. The update responds to major new evidence since the first Taipei statement (2020), including two very large community trials (JAMA 2024; Nat Med 2024), advances in eradication therapies (bismuth quadruple therapy, and potassium competitive acid blocker [PCAB]–based regimens), and fresh data on long-term safety (microbiome, antimicrobial resistance and oesophageal outcomes).

This article synthesises the core recommendations and evidence from Taipei Global Consensus II, emphasises what has changed since prior guidance, and translates the consensus into practical approaches for clinicians, public health planners and researchers.

New Guideline Highlights

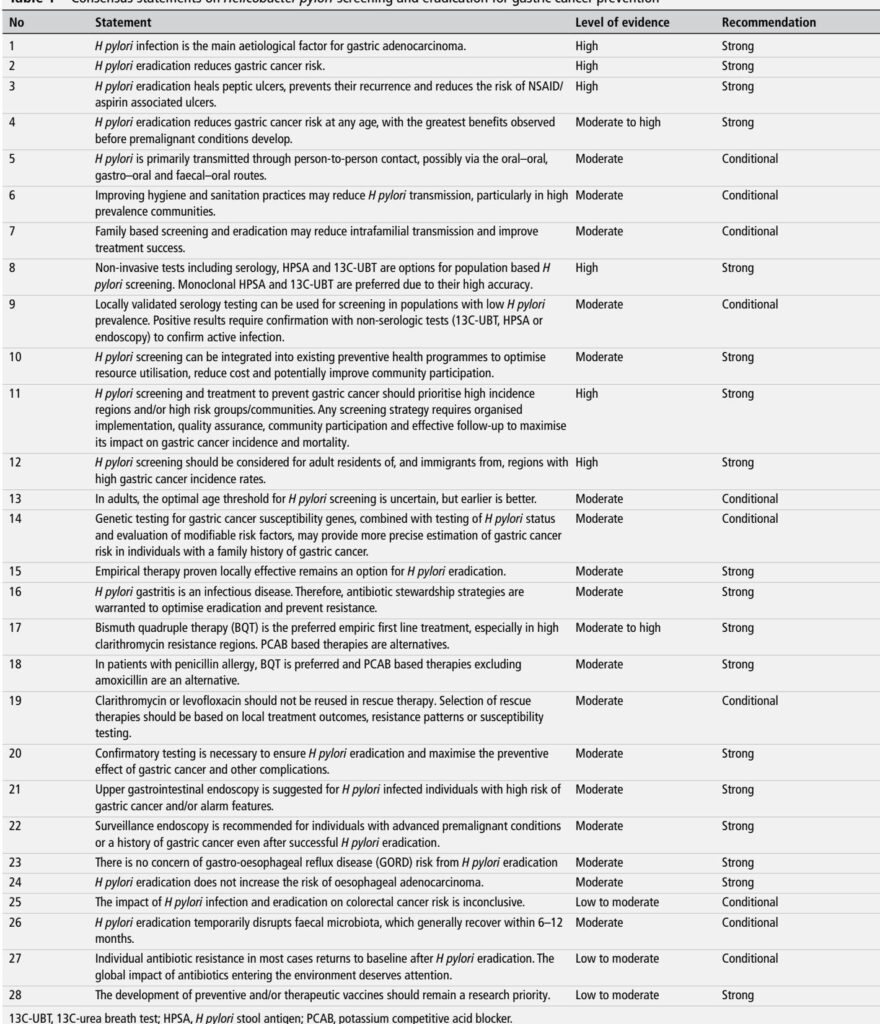

– Consensus scope: 32 experts from 12 countries; Delphi process produced 28 consensus statements using GRADE. (Liou JM et al., Gut 2025).

– Overarching conclusion: H. pylori eradication reduces gastric cancer risk and should be offered to all infected adults, with greatest benefit when achieved before premalignant changes develop (strong recommendation, evidence high–moderate).

– Screening focus: prioritise high-incidence regions and high-risk groups (residents and immigrants from high gastric cancer incidence areas).

– Diagnostics: non-invasive testing preferred for population screening—13C-urea breath test (13C-UBT) and monoclonal stool antigen (HPSA) are the preferred tests; locally validated serology may be used in low-prevalence settings provided positive results are confirmed with non-serologic testing.

– Treatment: empiric therapy remains acceptable when it is proven locally effective. Bismuth quadruple therapy (BQT) is the preferred empiric first‑line regimen, especially in areas with moderate–high clarithromycin resistance; PCAB (eg, vonoprazan)–based regimens (particularly vonoprazan–amoxicillin dual therapy) are recognised alternatives.

– Stewardship & safety: confirmatory testing after treatment is strongly recommended; antibiotic stewardship principles apply; eradication does not increase oesophageal adenocarcinoma risk and transient microbiome disruption generally resolves within 6–12 months.

– Program implementation: integrate H. pylori screening into existing preventive health programmes where possible; organise with quality assurance, community engagement and follow-up systems.

Key takeaways for clinicians:

– Offer testing and treatment to H. pylori–positive adults in high-risk settings; confirm eradication objectively (13C-UBT or HPSA).

– For empiric therapy favour BQT in settings with elevated macrolide resistance; use PCAB–amoxicillin dual therapy in appropriate settings.

– Do not reuse clarithromycin or levofloxacin for rescue therapy without susceptibility guidance.

Updated Recommendations and Key Changes (compared with Taipei 2020 and other prior guidance)

Major updates and what drove them:

– Stronger operational endorsement for population screening programmes. Why: two large pragmatic/community trials (JAMA 2024; Nat Med 2024) provided population-level evidence that screen-and-treat reduces gastric cancer incidence—though effect sizes were modest and influenced by adherence and trial design.

– Treatment regimen hierarchy updated: BQT remains top-line empiric choice where macrolide resistance is common; PCAB-based dual/triple regimens (eg, vonoprazan–amoxicillin) now have stronger support from recent RCTs and meta-analyses showing high eradication rates and favourable tolerability (Gut 2024–2025; Gastroenterology 2022).

– Confirmatory test emphasis: stronger recommendation that test-of-cure be performed routinely after therapy (4–6 weeks post-treatment using UBT or HPSA) to verify eradication and limit unnecessary retreatment.

– Family-based approaches: more explicit recommendation and economic modelling support for family-or household-targeted screening/eradication in high-prevalence communities to reduce reinfection.

– Safety considerations: systematic assessment of long-term microbiome and resistome impacts, and reassurance that eradication is not associated with increased oesophageal adenocarcinoma at the population level.

Summary table (concise):

– Who to screen: adults residing in or immigrated from high-incidence regions, and other high-risk subgroups (strong).

– Preferred screening tests: 13C-UBT or monoclonal stool antigen (strong).

– Serology: acceptable in low prevalence settings if locally validated and followed by confirmatory testing for positives (conditional).

– First-line empiric treatment: BQT preferred where clarithromycin resistance is moderate–high; PCAB-based regimens are alternatives (strong).

– Confirm eradication: mandatory in high-risk patients and strongly recommended generally (strong).

– Endoscopy: indicated for infected individuals with alarm features or additional high-risk markers; surveillance reserved for advanced premalignant changes or history of gastric cancer (strong).

Topic-by-Topic Recommendations

(Each item notes level of evidence and recommendation strength as presented by the consensus)

1) Causation and effect of eradication

– Statement: H. pylori is the principal cause of gastric adenocarcinoma (High evidence; Strong recommendation).

– Eradication reduces gastric cancer risk (High evidence; Strong). Meta-analyses and multiple RCTs and large cohort studies show relative risk reductions; mortality benefits also suggested.

2) Who to prioritise for screening

– Primary targets: adult residents of high gastric cancer incidence regions and immigrants from those regions (High evidence; Strong).

– Rationale: burden is concentrated geographically; cost-effectiveness models favour targeting higher-risk populations.

– Suggested practical approach: map local gastric cancer incidence, identify high-prevalence subpopulations (eg, certain ethnic groups, indigenous communities), and pilot organised programmes with invitation, testing, treatment and follow-up pathways.

3) Optimal age and timing

– Statement: optimal age is uncertain but earlier is better; earlier eradication (before premalignant lesions) offers greatest benefit (Moderate evidence; Conditional recommendation).

– Practical note: modelling and feasibility argue for screening ages often proposed between mid‑30s and mid‑40s in high-risk regions; integration with other screening (eg, colorectal FIT at age 45) may be pragmatic.

4) Screening tests and diagnostics

– Preferred tests: 13C-UBT and monoclonal HPSA (High evidence; Strong).

– Serology: acceptable in low-prevalence settings if assays are locally validated; positive serology must be confirmed with non‑serologic tests prior to treatment (Moderate evidence; Conditional).

– Test timing: avoid testing during or immediately after PPIs/PCABs (stop PPIs/PCABs 2 weeks, antibiotics/bismuth 4 weeks before testing) to avoid false negatives.

5) Treatment strategies

– Empiric therapy: allowed if locally effective (Moderate evidence; Strong).

– First-line: Bismuth quadruple therapy (BQT: PPI/PCAB + bismuth + tetracycline + metronidazole) preferred in settings with clarithromycin resistance; 10–14 day regimens recommended depending on local data. PCAB–amoxicillin dual therapy (eg, vonoprazan–amoxicillin) is an effective alternative supported by RCTs (Moderate–High evidence; Strong).

– Penicillin allergy: BQT preferred; PCAB regimens excluding amoxicillin are acceptable (Moderate evidence; Strong).

– Rescue/refractory therapy: avoid reuse of clarithromycin or levofloxacin without susceptibility confirmation; choose rescue regimens based on local resistance or AST (Conditional).

6) Antibiotic stewardship

– Core principle: H. pylori eradication is treatment of an infectious disease and must be guided by stewardship principles (Moderate evidence; Strong).

– Practical measures: select regimens least affected by prevalent resistance, use susceptibility-guided therapy when available (molecular or culture), confirm cure, monitor local eradication outcomes and resistance trends, and prioritise adherence support.

7) Confirmatory testing and endoscopy

– Confirm eradication: recommended 4–6 weeks after finishing therapy by 13C-UBT or HPSA (Moderate evidence; Strong).

– Upper endoscopy: suggested for infected individuals with alarm symptoms, family history of gastric cancer, abnormal serum pepsinogen, or other high‑risk features (Moderate evidence; Strong).

– Surveillance: recommended for those with advanced premalignant conditions (OLGA/OLGIM III–IV, open-type atrophy) or prior gastric cancer even after successful eradication (Moderate evidence; Strong).

8) Risks and long-term safety

– GORD and oesophageal adenocarcinoma: eradication does not increase long-term risk of oesophageal adenocarcinoma (Moderate evidence; Strong).

– Microbiota: eradication causes transient faecal microbiota perturbation, generally recovering within 6–12 months; clinical significance remains unclear (Moderate evidence; Conditional).

– Antimicrobial resistance: individual increases in resistance are often transient and return towards baseline, but population and environmental impacts require careful surveillance and stewardship (Low–Moderate evidence; Conditional).

9) Family and community approaches

– Family-based screening and treatment may reduce intrafamilial transmission and improve eradication success in high-prevalence communities (Moderate evidence; Conditional).

– Programmatic examples: Taiwan’s Matsu programme, other indigenous community initiatives and family-index methods illustrate feasibility and impact.

Expert Commentary and Insights

Consensus panel perspectives (paraphrased):

– “H. pylori eradication is now a validated, evidence-based primary prevention tool for gastric cancer in many settings.” (core view)

– Experts emphasise that the size of benefit varies by baseline risk, adherence and timing; the greatest population benefit accrues when programmes prioritise high-incidence settings and achieve high participation and verified eradication.

– The committee debated universal versus targeted screening; unanimity supported prioritising high-risk regions and groups while recommending pilot programmes and local evaluation elsewhere.

– Controversies remain: optimal age to start screening; the balance between broad eradication and antimicrobial stewardship; long‑term microbiome and population resistance consequences; and how best to combine H. pylori programmes with existing cancer screening services.

Key practical messages from experts:

– Implement screen-and-treat as an organised programme with quality metrics: invitation/enrolment rates, test uptake, treatment completion, test-of-cure rates and local eradication success rates.

– Use local resistance surveillance to guide empirical choices; where resistance testing is available, use molecular AST to tailor therapy.

– Ensure robust patient education and adherence support; consider fixed-dose or simplified regimens to improve completion rates.

Practical Implications: Translating Consensus into Practice

Health-system level considerations:

– Integrate H. pylori screening into existing preventive services (eg, combine stool antigen sampling with colorectal FIT where feasible) to save costs and leverage established invitation infrastructure (evidence and examples provided by JAMA pragmatic trial and Taiwan’s national platform).

– Pilot implementation: begin with high-incidence geographic areas or high-risk subpopulations to demonstrate feasibility, adjust referral pathways and refine cost-effectiveness locally.

Clinical practice workflow (suggested):

1. Identify candidate for screening (adult from high‑incidence area or other high‑risk criteria).

2. Offer non-invasive testing—prefer 13C-UBT or monoclonal stool antigen.

3. If positive, counsel on benefits/risks and offer eradication therapy with preferred regimen guided by local resistance.

4. After therapy, perform test-of-cure (13C-UBT or HPSA) at least 4–6 weeks after treatment completion and after stopping PPIs/PCABs.

5. If persistent infection, select rescue regimens based on susceptibility testing where available; avoid repeating macrolides/fluoroquinolones empirically.

6. For patients with alarm features, abnormal pepsinogen or family history, refer for endoscopy and risk stratification (OLGA/OLGIM).

Patient vignette (illustrative):

John, a 48‑year-old Korean‑American man with no alarm symptoms but a family history of gastric cancer (father diagnosed at 62), attends primary care. Given his background, he is offered H. pylori testing; a 13C-UBT is positive. After counselling, he receives a 14‑day BQT (local clarithromycin resistance >15%). He completes therapy with minor nausea. At 6 weeks post‑treatment a 13C‑UBT is negative—treatment success is documented. Given his family history, referral for upper endoscopy and baseline gastric mapping is arranged for risk stratification and surveillance planning per OLGA/OLGIM findings.

Future Research Priorities (consensus-ranked)

The guideline lists nine prioritised research areas. Key among them:

– Determining the optimal age for screening to maximise lifetime benefit and cost-effectiveness.

– Defining surveillance intervals and strategies for patients with premalignant lesions (OLGA/OLGIM stratified).

– Long-term studies on microbiome, metabolic and immune consequences of population-level eradication.

– Development and clinical testing of H. pylori vaccines (preventive and therapeutic) and non-antibiotic therapies (urease inhibitors, anti-adhesion agents).

– Large, multi-country implementation studies evaluating population outcomes, resistance ecology, and environmental impact of mass antibiotic use.

What Stayed the Same—Enduring Principles

– H. pylori remains a Group 1 carcinogen and an actionable target for gastric cancer prevention.

– Where endoscopy capacity exists and disease burden is very high, combining eradication with endoscopic screening remains a reasonable strategy.

– Confirmatory test-of-cure remains a cornerstone of good clinical practice to verify eradication and limit unnecessary retreatment.

Final Thoughts: Balancing Benefits, Harms and Feasibility

The 2025 Taipei Global Consensus II moves the field from conceptual endorsement of screen-and-treat toward practical, evidence‑based recommendations for implementation. The guidance underscores that eradication reduces gastric cancer risk and prevents peptic ulcer disease, but effects at the population level depend on program design: who is invited, which test is used, which regimen is chosen, and whether confirmatory testing and surveillance infrastructure are in place. Antibiotic stewardship and ongoing surveillance for resistance are essential, as is investment in research—particularly vaccine development and non‑antibiotic therapies—that would reduce reliance on systemic antibiotics.

For clinicians and public health leaders the message is clear: in settings where gastric cancer risk is elevated, organised H. pylori screen-and-treat programmes—built with quality assurance, community engagement and stewardship safeguards—are now supported by stronger evidence and pragmatic recommendations.

References

(Selected key references cited within this article; the full consensus contains a comprehensive reference list.)

1. Liou JM, Malfertheiner P, Hong TC, et al. Screening and eradication of Helicobacter pylori for gastric cancer prevention: Taipei Global Consensus II. Gut. 2025;74:1767–1791. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2025-336027.

2. Lee Y‑C, Chiang T‑H, Chiu H‑M, et al. Screening for Helicobacter pylori to Prevent Gastric Cancer: A Pragmatic Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2024;332:1642–1651.

3. Pan K‑F, Li W‑Q, Zhang L, et al. Gastric cancer prevention by community eradication of Helicobacter pylori: a cluster‑randomized controlled trial. Nat Med. 2024;30:3250–3260.

4. Malfertheiner P, Megraud F, Rokkas T, et al. Management of Helicobacter pylori infection: the Maastricht VI/Florence consensus. Gut. 2022;71:1724–1762.

5. Chey WD, Howden CW, Moss SF, et al. ACG Clinical Guideline: Treatment of Helicobacter pylori Infection. Am J Gastroenterol. 2024;119:1730–1753.

6. Best LM, Takwoingi Y, Siddique S, et al. Non‑invasive diagnostic tests for Helicobacter pylori infection. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;CD012080.

7. Liou JM, Jiang X‑T, Chen C‑C, et al. Second‑line levofloxacin‑based quadruple therapy versus bismuth‑based quadruple therapy and long‑term microbiota/resistome outcomes: Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;8:228–241.

8. Lee Y‑C, Chiang T‑H, Chou C‑K, et al. Association Between Helicobacter pylori Eradication and Gastric Cancer Incidence: A Systematic Review and Meta‑analysis. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:1113–1124.

9. Fukase K, Kato M, Kikuchi S, et al. Effect of eradication of Helicobacter pylori on incidence of metachronous gastric carcinoma after endoscopic resection: Lancet 2008;372:392–397.

10. WHO. Antimicrobial stewardship programmes in healthcare facilities (toolkit). Geneva: WHO; 2019.

(For a comprehensive list, see the full consensus article: Liou et al., Gut 2025.)