Introduction

Lead poisoning remains a significant public health concern globally, historically linked to cognitive deficits and developmental delays in children. However, mounting evidence suggests that the neurotoxic effects of lead extend beyond childhood, potentially influencing mental health outcomes in adulthood. The recent study examining the association between prenatal and early postnatal lead exposure, measured via deciduous teeth, and subsequent psychological health offers crucial insights into the timing and long-term impact of lead toxicity.

Background and Clinical Context

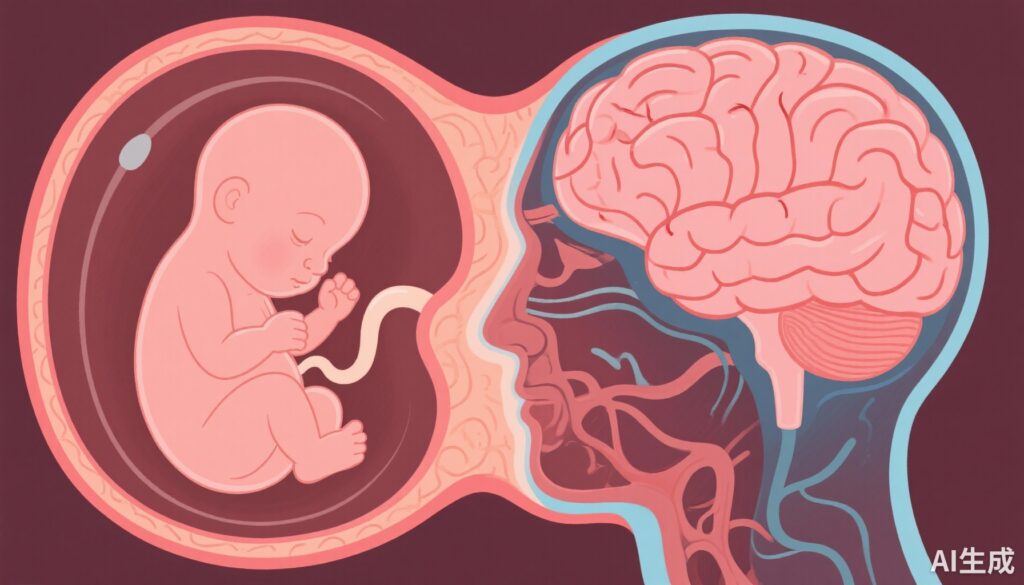

Lead exposure, historically prevalent in environments with contaminated paint, water, and soil, accumulates in the body, particularly in calcifying tissues like teeth. The critical periods of neurodevelopment, especially prenatal and early postnatal stages, are highly sensitive to toxic insults due to rapid brain growth and maturation. While the immediate effects of lead toxicity are well-documented, including cognitive impairment and behavioral disturbances, its potential role in adult mental health disorders is less understood.

Epidemiological data demonstrate associations between childhood lead levels and behavioral issues, but few studies focus on prenatal and early postnatal windows in relation to adult mood disorders. This gap in knowledge hampers the development of targeted prevention strategies and underscores the importance of understanding sensitive periods during neurodevelopment.

Study Design and Methods

This cohort study leveraged the Saint Louis Baby Tooth-Later Life Health Study (SLBT), involving participants who donated deciduous teeth in childhood during the 1950s through 1970s. The study recontacted 5,131 participants starting in 2021, with 718 providing teeth for lead analysis, and subsequently responding to health surveys at an average age of 62 years.

Lead exposure was quantified in baby teeth across multiple developmental windows: the second trimester, the third trimester (late prenatal), and early postnatal period (birth to 6 months). Psychological outcomes were assessed using validated instruments: the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) for depression and the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Screener-7 (GAD-7) for anxiety, with clinical cutoffs defining probable major depressive disorder and generalized anxiety disorder.

Statistical models adjusted for confounders such as socioeconomic status, education, and other environmental exposures to isolate the effects of lead concentrations during specific sensitive periods.

Key Findings

The study revealed a significant association between lead concentration in baby teeth and later adulthood depression. An interquartile range (IQR) increase in combined tooth lead was associated with nearly twice the odds of clinically significant depressive symptoms (OR 1.90, 95% CI 1.20-2.99). Notably, the late prenatal period (approximately the third trimester) emerged as the most sensitive window, with an OR of 1.55 (95% CI 1.23-1.97). This suggests that lead exposure during late pregnancy critically impacts neural pathways involved in mood regulation.

In contrast, although no significant association was found with the diagnosis of generalized anxiety disorder, elevated lead levels during late prenatal and early postnatal periods correlated with increased anxiety symptom scores. This indicates that certain neurobehavioral pathways may be differentially sensitive to lead depending on the developmental timing.

Quantitative analysis of lead levels showed a median concentration of 1.34 ppm, with higher levels correlating with increased adult depression scores. The findings demonstrate a dose-response pattern, reinforcing the importance of window-specific interventions.

Expert Commentary

This study underscores the importance of viewing lead exposure as a lifelong risk factor rather than merely a childhood concern. The identification of late prenatal exposure as the most sensitive period aligns with biological mechanisms of brain development, including synaptogenesis and myelination, which are particularly vulnerable during the third trimester.

While the findings are compelling, limitations include reliance on dental lead as a retrospective biomarker and potential residual confounding. Nevertheless, the data bolster the argument for rigorous regulation of lead exposure and augmentation of screening programs for at-risk populations.

Mechanistically, lead interference with neurotransmitter systems, oxidative stress pathways, and neuroinflammation may underpin the observed associations. Future research should explore epigenetic modifications and gene-environment interactions influencing these outcomes.

Implications for Practice and Policy

The evidence advocates for intensified efforts to prevent lead exposure during pregnancy, including public health policies targeting environmental pollution and housing safety. Moreover, individuals with known prenatal lead exposure may benefit from screening for mental health issues, enabling early intervention.

Health providers should be aware of the long-term neuropsychological consequences of lead, considering psychosocial and pharmacological treatments where appropriate. Longitudinal follow-up and support services can mitigate the enduring impact of early environmental insults.

Summary and Future Directions

This study highlights the enduring influence of prenatal lead exposure on adult mental health, emphasizing the importance of the late prenatal period as a sensitive window. The findings call for integrative strategies combining environmental health policies, early screening, and targeted mental health services to address the legacy of lead toxicity.

Further research should investigate underlying biological mechanisms, explore interventions during sensitive periods, and develop biomarkers for early detection of at-risk individuals. Ultimately, reducing lead exposure remains a critical goal in fostering healthier neurodevelopmental trajectories and mental health outcomes across the lifespan.