Highlights

- Perinatal antibiotic exposure (maternal and/or neonatal) is associated with significant shifts in the gut microbiota of preterm infants, favoring pathogenic bacteria over beneficial species.

- Combined maternal and neonatal antibiotic exposure leads to greater dysbiosis and higher gut-blood microbial correlations, suggesting increased risk for bloodstream infections.

- Exclusive breastfeeding supports the recovery and maintenance of beneficial gut flora, particularly Bifidobacterium spp., even after antibiotic exposure.

- The presence of causative pathogens in the gut preceding bloodstream infection highlights the gut as a reservoir and potential source for neonatal sepsis.

Study Background and Disease Burden

The human gut microbiota plays a pivotal role in neonatal immune programming, metabolic development, and protection against pathogens. Preterm infants are particularly vulnerable to disruptions in microbial colonization due to factors such as immature immunity, frequent medical interventions, and, notably, antibiotic exposure. Antibiotics are commonly administered perinatally—either to mothers during labor (for infection prophylaxis) or to neonates in response to suspected sepsis. While antibiotics are lifesaving when warranted, their use in this critical window may have unintended consequences, including altered microbial succession, increased risk of necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC), and predisposition to late-onset sepsis. However, the precise effects of perinatal antibiotic exposure, especially the combined impact of maternal and neonatal regimens, on the structure and function of the preterm infant gut microbiome remain inadequately characterized.

Study Design

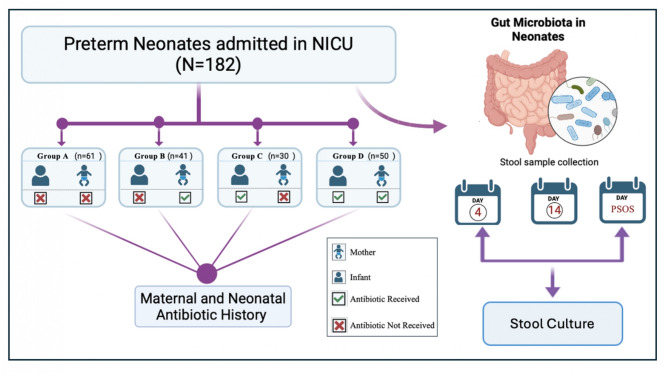

This prospective controlled cohort study was conducted in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) of a tertiary care hospital in India from January 2021 to September 2023. The study enrolled 182 preterm infants (gestational age <37 weeks), systematically categorized into four groups based on antibiotic exposure:

- NE group: No exposure to maternal or neonatal antibiotics before stool sample collection

- IE group: Infant exposure only (postnatal antibiotics)

- ME group: Maternal exposure only (intrapartum antibiotics)

- IME group: Both infant and maternal exposure

A total of 364 stool samples were collected for analysis. Microbiota composition was assessed using traditional convection culture methods, and blood cultures were matched to stool isolates to investigate gut-blood microbial correlations. Feeding practices (breastfeeding, formula, or mixed feeds) were also recorded to assess their impact on microbial recovery.

Key Findings

1. Microbial Shifts and Pathogenic Overgrowth

By day 4, Klebsiella pneumoniae was significantly more prevalent in the IE group (70%) compared to the NE group (42.6%, p < 0.001). Similarly, Bifidobacterium spp.—a hallmark of healthy neonatal gut flora—were more prevalent in the NE group (57.4%, p = 0.019) than in any antibiotic-exposed group. These trends suggest that antibiotic exposure, particularly in the neonate, selectively suppresses beneficial commensals and permits the expansion of opportunistic pathogens.

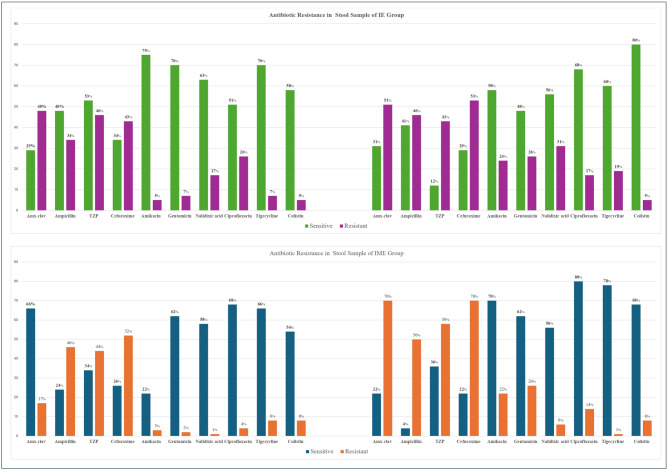

Antibiotic resistance in stool samples of the IE and IME groups

2. Gut-Blood Microbial Correlation and Infection Risk

The study found that in 75% of invasive infection cases, the same pathogenic species dominated the gut microbiota prior to bloodstream infection, with Klebsiella pneumoniae, Escherichia coli, and Enterobacter spp. most frequently implicated. Gut–blood microbial correlation was higher in the IME group (40% on day 4 and 36% on PSOS day) compared to the IE group (24% and 26% respectively), indicating a possible dose-dependent effect of combined maternal and neonatal antibiotic exposure on gut barrier integrity and bacterial translocation.

3. Impact of Feeding Practices

Breastfeeding was associated with better colonization by Bifidobacterium spp. in both the IE and IME groups (up to 80%), underscoring the restorative potential of human milk oligosaccharides and bioactive compounds. In contrast, formula-fed neonates, particularly those with dual antibiotic exposure (IME), experienced delayed recovery of beneficial flora and persistent dominance of potentially pathogenic species. Enterococcus faecalis remained consistently abundant post-antibiotic exposure across feeding types, suggesting a degree of resilience or niche adaptation.

4. Microbial Diversity and Dysbiosis

Combined maternal and neonatal antibiotic exposure resulted in greater overall dysbiosis, reflected in decreased E. coli diversity and prolonged suppression of Bifidobacterium recovery, particularly among non-breastfed infants. The findings indicate that both the timing and combination of antibiotic exposures can have additive disruptive effects on the neonatal gut ecosystem.

Expert Commentary

These results reinforce the growing concern in neonatology that perinatal antibiotic administration, while necessary in many clinical scenarios, is not without risk, particularly for preterm infants whose gut microbiota is highly susceptible to perturbation. The observed association between gut colonization by pathogenic bacteria and subsequent bloodstream infection is biologically plausible, as antibiotics disrupt normal colonization resistance, reduce immune priming, and enhance the potential for gut-derived sepsis. The study also highlights the significant, protective influence of exclusive breastfeeding in supporting microbial recovery, in line with current recommendations from the World Health Organization and various neonatal guidelines.

However, several limitations must be acknowledged. The use of culture-based methods, while practical, may underestimate the complexity and diversity of the microbiota compared to metagenomic sequencing. The study was conducted at a single center, which may limit generalizability, and the focus on preterm infants may not extend to term neonates. Confounding factors, such as type and duration of antibiotic exposure, maternal health, and environmental factors, may also influence microbial outcomes.

Conclusion

Perinatal antibiotic exposure in preterm infants—particularly when both maternal and neonatal antibiotics are used—disrupts gut microbial colonization, increases the abundance of potentially pathogenic species, and is associated with a higher risk of gut-derived bloodstream infections. Exclusive breastfeeding emerges as a critical modulator, promoting the expansion of beneficial commensals even after antibiotic perturbation. These findings support judicious use of antibiotics in the perinatal period, prioritization of human milk feeding, and consideration of targeted strategies (such as probiotic supplementation) to restore microbial balance in high-risk neonatal populations. Further multicenter studies using advanced sequencing technologies are warranted to delineate the mechanistic pathways involved and to inform evidence-based clinical guidelines.

References

1. Iqbal F, Shenoy PA, Lewis LES, Siva N, Purkayastha J, Eshwara VK. Influence of perinatal antibiotic on neonatal gut microbiota: a prospective cohort study. BMC Pediatr. 2025 Jul 21;25(1):560. doi: 10.1186/s12887-025-05907-y IF: 2.0 Q2 . PMID: 40685344 IF: 2.0 Q2 ; PMCID: PMC12278547 IF: 2.0 Q2 .

2. Cantey JB, Milstone AM. Bloodstream infections in children: Epidemiology and clinical management. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2022;20(1):1-16.3. Tamburini S, Shen N, Wu HC, Clemente JC. The microbiome in early life: implications for health outcomes. Nat Med. 2016;22(7):713-22.4. World Health Organization. Guideline: Protecting, promoting and supporting breastfeeding in facilities providing maternity and newborn services. Geneva: WHO; 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2017.03.012 .