Background

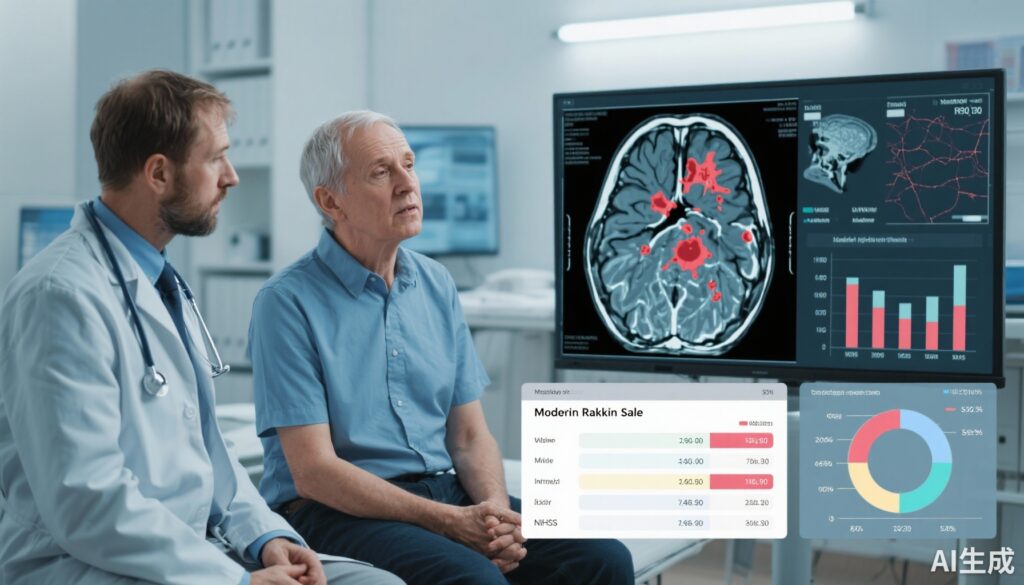

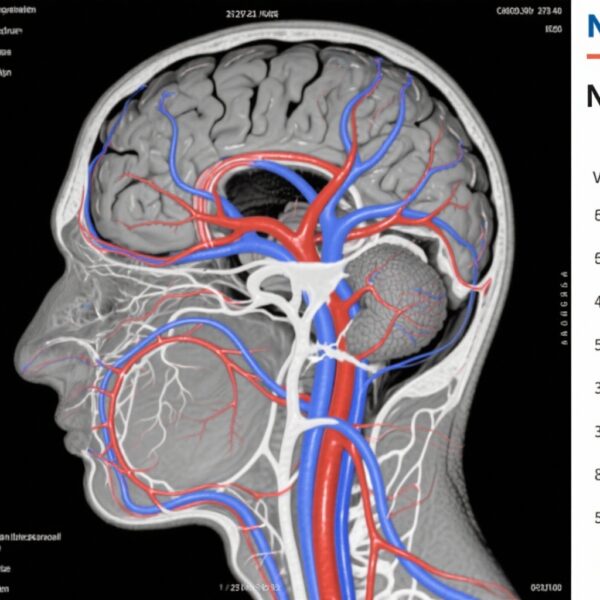

Minor ischemic stroke presents a therapeutic dilemma in acute stroke management. While thrombolytic therapy with intravenous alteplase is established for moderate to severe ischemic stroke, its benefit in patients with minor stroke remains uncertain. Minor ischemic strokes, often defined by a National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) score of 5 or less, represent a heterogeneous group with varying potential for disability. Determining which patients with minor stroke may benefit from alteplase is critical, as the risk-to-benefit ratio must be carefully weighed given the risk of hemorrhagic complications.

In clinical practice, defining “disabling” minor stroke is controversial, leading to varied treatment approaches worldwide. Some minor strokes that affect motor function, speech, or consciousness can cause considerable disability despite low NIHSS scores. The Third China National Stroke Registry (CNSR-III) provides a robust prospective dataset to explore the real-world effectiveness and safety of alteplase in this population.

Study Design and Methods

This prospective cohort study utilized data from CNSR-III collected from August 2015 to March 2018. The study included 2,489 adult patients diagnosed with minor ischemic stroke (NIHSS ≤5). Patients were stratified into two groups based on treatment received: intravenous alteplase versus standard medical therapy without thrombolysis. Exclusion criteria included incomplete 90-day follow-up for functional outcomes.

Disabling minor stroke was operationally defined as minor stroke accompanied by one or more of the following: consciousness impairment, motor deficits, limb ataxia, or communication deficits. Subgroup analyses accounted for NIHSS subitems and etiologic classifications according to TOAST criteria, particularly focusing on patients with large artery atherosclerosis (LAA).

The primary efficacy outcome was excellent functional outcome at 90 days post-stroke, defined as a modified Rankin Scale (mRS) score of 0-1. Secondary outcomes included the distribution shift in mRS scores, good functional outcome (mRS ≤2), and stroke recurrence within 90 days. Safety endpoints emphasized the incidence of in-hospital bleeding complications and 90-day mortality.

Multivariable regression models (log-binomial, logistic, and Cox) adjusted for relevant confounders to evaluate treatment associations with outcomes.

Key Findings

Among the 2,489 enrolled patients (median age 63 years; 70.1% male), 611 (24.5%) received alteplase. Complete functional outcome data at 90 days were available for 2,462 patients.

In the overall cohort, alteplase usage did not yield a statistically significant benefit for the primary outcome—excellent functional outcome (87.0% vs. 83.8% in non-treated; adjusted relative risk [RR] 1.02, 95% CI 0.99–1.04; p > 0.05).

Notably, in the subgroup with NIHSS scores greater than 3 or classified as having disabling minor stroke (n=849), alteplase was associated with a significantly higher proportion achieving excellent functional outcomes at 90 days (82.1% vs. 74.1%; adjusted RR 1.12, 95% CI 1.04–1.20). These patients also demonstrated favorable shifts in the overall mRS distribution (adjusted common odds ratio [cOR] 1.62, 95% CI 1.22–2.14), indicative of clinically meaningful improvement.

Similarly, combining patients with NIHSS >3, disabling minor stroke, or LAA etiologic subtype (n=1,217) showed consistent efficacy signals (adjusted RR for excellent outcome 1.11, 95% CI 1.05–1.18) without significant increases in safety risks.

Safety analyses revealed low and comparable in-hospital bleeding rates between groups (alteplase 3.0% vs. standard treatment 1.4%) and no significant difference in 90-day mortality (0.4% vs. 2.1%). This reaffirms the safety profile of alteplase in carefully selected minor stroke patients.

Expert Commentary

This large registry study addresses a crucial clinical uncertainty about thrombolysis in minor ischemic stroke patients. The findings underscore that blanket application of alteplase in all minor stroke patients may not confer additional benefit. Instead, patient selection based on NIHSS score thresholds and disabling symptoms is paramount to optimize outcomes, consistent with current guideline recommendations emphasizing individualized risk assessment.

The study’s strengths include its prospective nationwide design, robust functional and safety outcome measures, and stratified subgroup analyses reflecting clinical heterogeneity. However, limitations inherent to registry data, such as potential residual confounding and treatment selection bias despite adjustments, temper causal inference.

Furthermore, the definition of disabling minor stroke relies on clinical constructs that may differ across settings. Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) focusing on these subgroups are needed to confirm these observational findings. Recent RCTs like PRISMS and TEMPO-2 have also explored thrombolysis in mild strokes with mixed outcomes, indicating ongoing equipoise.

Mechanistically, patients with mild but functionally impactful deficits or LAA etiology may benefit more as their symptoms stem from strategically located ischemia or ongoing artery-to-artery embolization, which intravenous thrombolysis could ameliorate.

Conclusion

This nationwide analysis from CNSR-III reveals no clear benefit of intravenous alteplase across all minor ischemic stroke patients. However, subsets defined by NIHSS >3, disabling minor stroke features, or large artery atherosclerosis display improved functional outcomes with alteplase without increased hemorrhagic risk. These findings support a tailored approach to thrombolysis in minor stroke rather than uniform administration.

Future RCTs are warranted to definitively establish efficacy and safety in these subpopulations and refine clinical decision-making algorithms. Meanwhile, clinicians should apply nuanced clinical judgment incorporating stroke severity, disabling features, and stroke subtype when considering alteplase for minor ischemic stroke.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grants 81870905, U20A20358) and Beijing Hospitals Authority (QML20210501, PX2021024).

References

1. Yin JF, Jing J, Meng X, Lin JX, Jiang Y, Li H, Wang YJ, Gu HQ. Alteplase treatment in patients with minor ischemic stroke: a nationwide registry analysis. EClinicalMedicine. 2025 Sep 23;89:103523. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2025.103523.

2. Powers WJ, Rabinstein AA, Ackerson T, et al. 2018 Guidelines for the Early Management of Patients With Acute Ischemic Stroke. Stroke. 2018;49(3):e46-e110.

3. Coutts SB, Hill MD. The PRISMS Trial: Thrombolysis for Minor Stroke. Stroke. 2019;50(8):2200-2202.

4. Khatri P, Kleindorfer DO, Yeatts SD, et al. Effect of alteplase vs aspirin on functional outcome for patients with acute ischemic stroke and minor nondisabling neurological deficits: The PRISMS randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2018;320(2):156-166.

5. Emberson J, Lees KR, Lyden P, et al. Effect of treatment delay, age, and stroke severity on the effects of intravenous thrombolysis with alteplase: a meta-analysis of individual patient data from randomised trials. Lancet. 2014;384(9958):1929-1935.