Background

Acute-on-chronic liver failure (ACLF) is a multifaceted syndrome arising from acute deterioration in patients with chronic liver disease of varying aetiologies, with high short-term mortality and substantial global health impact. Despite multiple diagnostic frameworks established regionally—such as the European CLIF criteria predominantly derived from alcohol- and hepatitis C-related populations, and the Chinese COSSH criteria developed in hepatitis B virus (HBV)-endemic settings—there is currently no universally accepted, practical diagnostic and prognostic system applicable worldwide across heterogeneous ACLF etiologies. Given evolving epidemiologic trends with decreasing hepatitis C and increasing alcohol-related liver injury globally, an evaluation of frameworks that perform well across diverse populations is imperative to harmonize clinical practice and improve outcomes globally.

Study Design

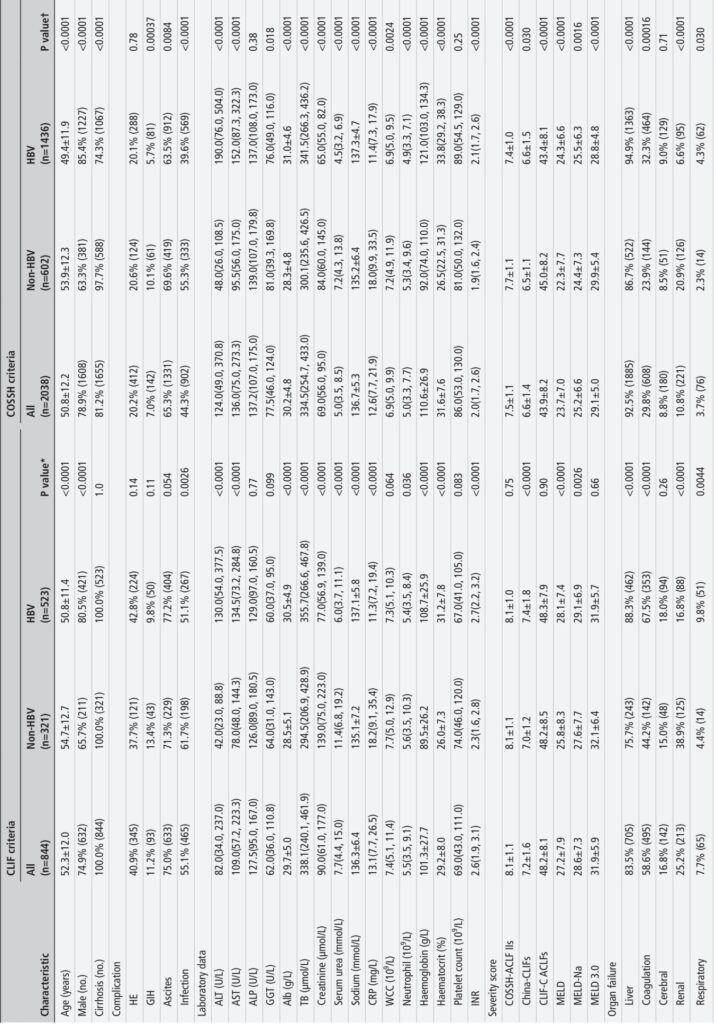

This prospective multicenter study enrolled 5,288 patients hospitalized with acute deterioration of chronic liver disease from January 2018 to August 2023, representing diverse etiologies including HBV and non-HBV causes (alcohol, autoimmune, parasitic, drug-induced, and HCV-related etiologies). Patients were assessed at admission for the presence of ACLF using both the European CLIF and Chinese COSSH diagnostic criteria. The study also evaluated performance of seven prognostic scores—the COSSH-ACLF II score (COSSH-ACLF IIs), China-CLIFs (modified from CLIF-C ACLFs), CLIF-C ACLFs, MELD, MELD-Na, MELD 3.0, and NACSELD-ACLFs—for predicting 28-day and 90-day liver transplantation (LT)-free mortality. Validation was conducted in three large non-Asian cohorts totaling 4,072 patients from Europe and Latin America (CANONIC, PREDICT, ACLARA). Extensive clinical, laboratory, and outcome data were systematically collected and analyzed.

Key Findings

1. Diagnostic Performance: The COSSH criteria identified 2,038 ACLF patients (38.5%), markedly higher than 844 patients (16.0%) identified by CLIF criteria. COSSH criteria captured an additional 22.6% of critically ill patients who demonstrated organ failure and significant mortality, including 14.2% additional non-HBV patients otherwise missed by CLIF criteria.

2. Mortality and Severity Distribution: COSSH-classified ACLF patients showed graded 28-day/90-day LT-free mortality rates (27.3%/41.0%), significantly lower than CLIF-classified patients (40.7%/57.0%), reflecting COSSH’s inclusion of patients with less severe but clinically important disease. COSSH criteria produced a more reasonable epidemiological pyramid-like distribution across ACLF grades 1 to 3 (63.4%/27.5%/9.1%) compared with CLIF’s skew towards grade 2 (25.8%/56.3%/17.9%).

3. Organ Failure Profiles: Differences in organ failure patterns were observed according to etiology, with HBV-ACLF characterized by higher liver and coagulation failure rates, whereas non-HBV-ACLF patients exhibited predominant renal failure. COSSH criteria better reflected these differences by expanding inclusion to non-cirrhotic patients and those with single liver failure plus elevated INR.

4. Prognostic Performance: COSSH-ACLF II score demonstrated superior discrimination for 28-day and 90-day LT-free mortality prediction across all ACLF patients and etiologies, outperforming CLIF-C ACLF and other established scores. It showed excellent calibration and effective risk stratification into low-, intermediate-, and high-risk groups with significantly different mortality risks.

5. External Validation: In non-Asian validation cohorts, China-CLIFs score performed equivalently to CLIF-C ACLF at predicting mortality in cirrhotic patients of predominantly non-HBV etiology, significantly outperforming MELD-based models and NACSELD-ACLFs. Though direct external validation of COSSH-ACLF IIs was not feasible due to missing urea data, a matched subset analysis indicated comparable prognostic accuracy.

Expert Commentary

This comprehensive study addresses a critical gap by evaluating diagnostic and prognostic frameworks across the full spectrum of ACLF etiologies, including HBV and non-HBV populations, with rigorous validation in diverse global cohorts. The findings underscore the limitations of existing criteria that either under-diagnose (CLIF) or focus on very severe cases (NACSELD), and affirm the enhanced sensitivity and balanced specificity of the China-CLIF framework (integrating COSSH and CLIF elements).

The expanded inclusion criteria of COSSH capture a larger subset of patients at high risk who may benefit from early intensive management or transplantation consideration. Importantly, the COSSH-ACLF II prognostic score’s superior predictive validity with fewer variables may facilitate easier clinical implementation.

However, limitations include potential regional diagnostic variability, reliance on single time-point scoring without dynamic assessment, and the need for broader external validation across varying healthcare systems and emerging etiologies such as metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD). Future work integrating multiomic biomarkers may yield biologically driven classifications to improve personalized management of ACLF.

Conclusion

The China-CLIF framework provides a robust, widely applicable diagnostic and prognostic system for ACLF that is sensitive across diverse liver disease etiologies and geographies. By bridging prior gaps between Asian and Western definitions, it offers a unified foundation to harmonize ACLF nomenclature, enhance early identification of at-risk patients, and inform treatment prioritization globally. Adoption of this framework promises to reduce disparities in ACLF management and catalyze therapeutic advances through international collaboration.

References

1. Arroyo V, Moreau R, Jalan R. Acute-on-Chronic Liver Failure. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:2137–45.

2. Moreau R, Gao B, Papp M, et al. Acute-on-chronic liver failure: A distinct clinical syndrome. J Hepatol. 2021;75:S27–35.

3. Wu T, Li J, Shao L, et al. Development of diagnostic criteria and a prognostic score for hepatitis B virus-related acute-on-chronic liver failure. Gut. 2018;67:2181–91.

4. Moreau R, Jalan R, Gines P, et al. Acute-on-chronic liver failure is a distinct syndrome that develops in patients with acute decompensation of cirrhosis. Gastroenterology. 2013;144:1426–37.

5. Jalan R, Yurdaydin C, Bajaj JS, et al. Toward an Improved Definition of Acute-onChronic Liver Failure. Gastroenterology. 2014;147:4–10.

6. Bernal W, Jalan R, Quaglia A, et al. Acute-on-chronic liver failure. Lancet. 2015;386:1576–87.

7. Sarin SK, Choudhury A. Acute-on-chronic liver failure: terminology, mechanisms and management. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;13:131–49.

8. Karvellas CJ, Bajaj JS, Kamath PS, et al. AASLD Practice Guidance on Acute-on-chronic liver failure and the management of critically ill patients with cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2024;79:1463–502.

9. Luo J, Li J, Li P, et al. Acute-on-chronic liver failure: far to go—a review. Crit Care. 2023;27:259.

10. Zaccherini G, Weiss E, Moreau R. Acute-on-chronic liver failure: Definitions, pathophysiology and principles of treatment. JHEP Rep. 2021;3:100176.