Introduction: The Ubiquity of Plastic Pollution

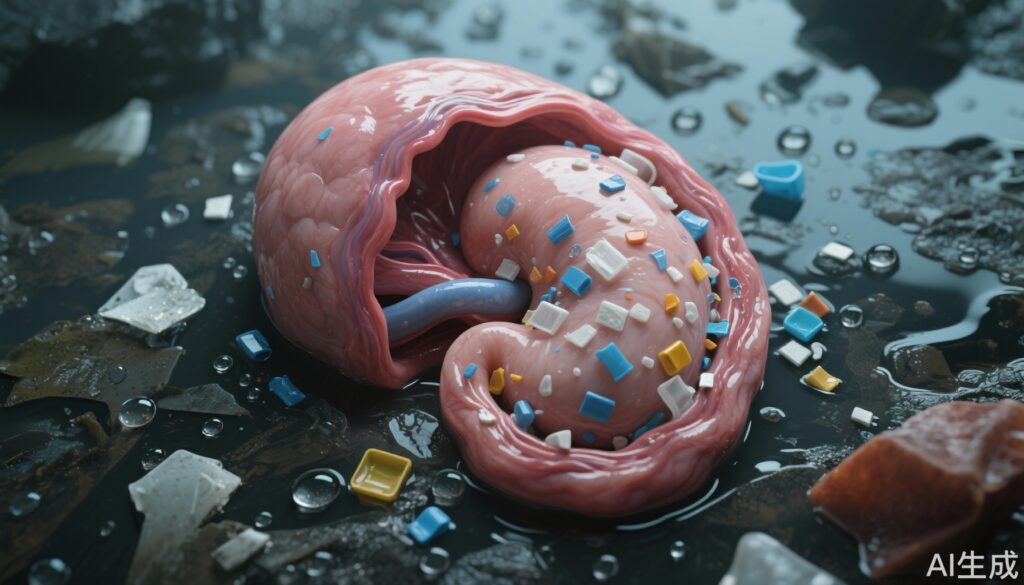

Have you ever considered where the plastic waste around us ultimately ends up? Beyond polluting our oceans and soils, new scientific evidence reveals that microscopic plastic fragments have infiltrated one of the most vital interfaces in human development: the placenta.

Microplastics are tiny plastic particles measuring less than 5 millimeters. Even smaller than microplastics are nanoplastics, which range from nanometer to micrometer scales. These minuscule particles possess unique properties that enable them to permeate ecosystems and enter the human food chain, potentially reaching critical maternal and fetal tissues.

The placenta grows during pregnancy to supply oxygen and nutrients to the developing fetus. Until recently, the extent of environmental contaminants like microplastics in this organ remained unclear.

Scientific Evidence: Microplastics in the Human Placenta

A landmark study from the University of New Mexico, published in Toxicological Sciences, adopted novel methodologies to analyze micro- and nanoplastic presence in human placentas. Researchers examined 62 placenta samples and astonishingly found microplastic particles in every single specimen.

Results showed microplastic concentrations ranging from 6.5 micrograms to 685 micrograms per gram of placental tissue, with an average of 126.8 ± 147.5 micrograms per gram. While short-term health effects are not yet fully understood, the high and persistent exposure levels suggest potentially serious consequences for both maternal and fetal health.

Regarding the types of plastics detected, polyethylene accounted for 54% of all microplastics — a ubiquitous plastic almost always present in the samples. Polyvinyl chloride (PVC) and nylon each made up roughly 10%, with various other plastics comprising the remaining 26%.

Environmental Pathways: How Do Microplastics Reach the Placenta?

Since the 1950s, plastic production has skyrocketed, yet roughly two-thirds of all manufactured plastics have been discarded into landfills or the environment. Under sunlight and weathering, plastics degrade into progressively smaller fragments, eventually entering groundwater and air as aerosolized particles.

Consequently, humans are exposed to microplastics not only through ingestion of contaminated water and food but also via inhalation. These particles accumulate inside the body over months to years. Although traditionally considered inert, recent studies suggest that nanoplastics—smaller than one-thousandth the width of human hair—may penetrate cellular membranes, exposing internal tissues to their effects.

The placenta’s high blood flow increases its vulnerability to such microscopic intruders, making it a key site of exposure during fetal development.

Potential Health Implications and Current Unknowns

Evidence indicates microplastic exposure already begins in early fetal stages. However, the precise impact on pregnancy outcomes and long-term health remains uncertain. Some hypotheses propose that microplastic-induced inflammation or toxicity could underlie puzzling rises in inflammatory bowel disease, early-onset colorectal cancer, and declining sperm counts observed in recent decades.

Animal studies bolster these concerns: ingestion of polystyrene nanospheres has been shown to transfer to the placenta and fetal tissues in pregnant rats, while exposure to polystyrene micro- and nanoplastics can impair placental function in mice.

Given that the placenta accumulates substantial microplastic loads over only eight months, other organs exposed over lifetimes could harbor even higher levels, posing unknown risks.

Environmental Persistence: The Long-Term Picture of Plastic Pollution

Despite calls to reduce plastic production, environmental microplastics are expected to triple by 2050, even if manufacturing ceased immediately. Many plastics have half-lives of hundreds of years, effectively rendering them permanent residents in ecological and biological systems on human timescales.

As these persistent plastics continue to degrade into nanoplastics over centuries, their potential to infiltrate human tissues—and influence health—will only grow.

Expert Insights

Dr. Ana Borbely, co-author of the study, remarks, “The ubiquitous presence of microplastics in placental tissue challenges us to reconsider how pervasive this pollution is and its implications for fetal health. This study underscores the urgency of understanding the clinical impacts and developing preventive strategies.”

Patient Scenario: Expectant Mother Emily’s Concerns

Emily, a 30-year-old pregnant woman, learns about microplastic contamination in placentas during her prenatal visit. Concerned for her baby’s health, she asks her obstetrician how to minimize exposure.

The clinician advises Emily to reduce contact with single-use plastics, use purified water, and maintain a diet rich in antioxidants to potentially counterbalance environmental pollutants, while acknowledging that research on mitigation is ongoing.

Conclusion: Toward a Plastic-Free Future for Maternal and Child Health

The discovery of microplastics in every human placenta examined is a sobering indication of the extent to which human-made pollution has permeated our biology. While causal links to adverse pregnancy outcomes require further investigation, the precautionary principle urges reducing plastic pollution and exposure.

Advances in detection and clinical correlation are crucial to uncovering the health effects of placental microplastics. Protecting developing life from these invisible contaminants must be a priority for public health and environmental policies worldwide.

References

Oliveira CWL, Oliveira LFAM, Garcia J, Weingrill RB, Urschitz J, Souza ST, Fonseca EJS, Ospina-Prieto S, Borbely AU. First evidence of microplastic accumulation in placentas and umbilical cords from pregnancies in Brazil. An Acad Bras Cienc. 2025 Jul 25;97Suppl 3(Suppl 3):e20241298. doi: 10.1590/0001-3765202520241298. PMID: 40736112.