Highlight

- Exposure to ambient air pollutants including nitrogen dioxide (NO2), nitrogen oxides (NOx), and particulate matter (PM10) during midlife is linked to slower processing speed and impaired verbal memory between ages 43 and 69.

- Higher midlife air pollution exposure correlates with poorer general cognitive state at age 69, as measured by the Addenbrooke’s Cognitive Examination III (ACE-III).

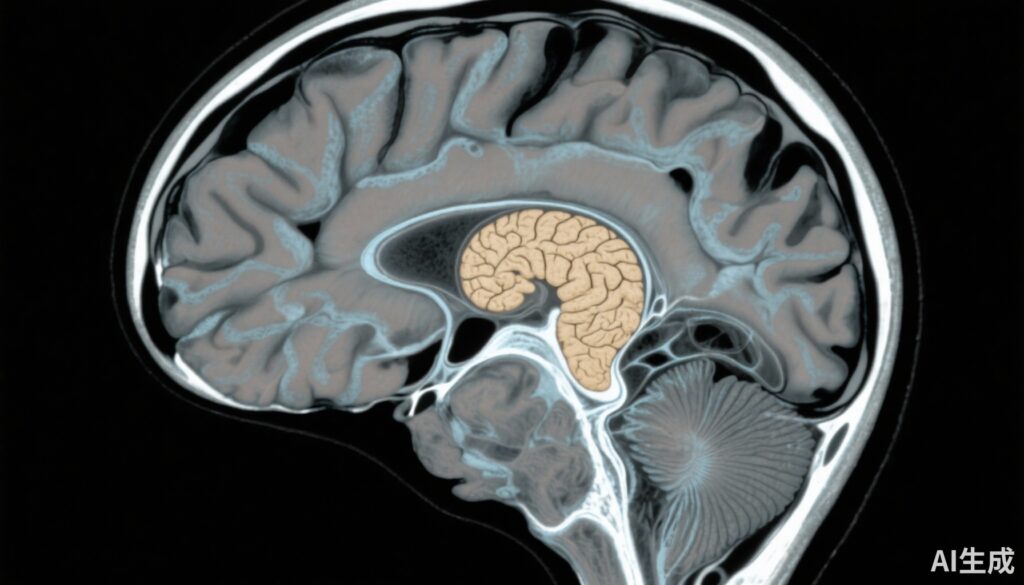

- Neuroimaging data from ages 69 to 71 show increased ventricular volume and reduced hippocampal volume associated with higher exposures to NO2, NOx, and PM10, indicating adverse brain structural changes.

- The findings underscore the importance of considering long-term, life-course environmental exposures in the evaluation of cognitive aging and neurodegeneration risk.

Study Background

Ambient air pollution is a global environmental health concern increasingly implicated not only in respiratory and cardiovascular disease but also in adverse neurological outcomes. Prior epidemiological studies have linked higher levels of air pollution exposure in older adults to increased risks of cognitive impairment and dementia. However, most studies have predominantly focused on late-life exposures, while the influence of pollution accumulated across the life course remains less understood. Given that neurodegenerative processes may initiate decades before clinical symptoms, assessing midlife exposures and their impact on cognition and brain structure in later life is crucial. This study addresses gaps by leveraging the well-characterized 1946 British Birth Cohort (Medical Research Council National Survey of Health and Development [NSHD]) and its neuroimaging substudy (Insight 46) to investigate associations between air pollution exposure from midlife onwards and cognitive outcomes in older age.

Study Design

This population-based cohort study analyzed data from the NSHD, consisting of individuals born during one week in March 1946 in Britain, with longitudinal follow-up and cognitive assessments conducted at ages 43, 53, 60-64, and 69 years. A subset of 502 participants underwent detailed brain MRI at ages 69-71 as part of Insight 46. Air pollution exposure metrics included nitrogen dioxide (NO2) from ages 45-64 years; particulate matter less than 10 μm (PM10) from ages 55-64; and nitrogen oxides (NOx), particulate matter less than 2.5 μm (PM2.5), coarse particulate matter (2.5-10 μm), and particulate matter absorbance (PM2.5abs) as a measure of black carbon from ages 60-64 years. The exposure assessment also adjusted for early-life exposure to black smoke and sulfur dioxide.

Cognitive testing comprised a 15-item verbal memory recall task and a visual search processing speed task across examinations. At age 69, global cognitive state was assessed using the Addenbrooke’s Cognitive Examination III (ACE-III). MRI outcomes included whole brain volume, ventricular volume, hippocampal volume, and white matter hyperintensity volume. Analyses controlled for sociodemographic factors, smoking, and neighborhood deprivation, employing generalized linear and mixed models to explore associations.

Key Findings

The verbal memory and processing speed analysis included 1,534 individuals; 1,761 participants completed the ACE-III cognitive assessment; and 453 participants contributed brain imaging data.

Significant associations emerged between higher midlife exposure to NO2 and PM10 and slower processing speed over ages 43 to 69 years, with effect sizes indicating meaningful cognitive slowing per interquartile range increase in pollutant exposure (NO2 β -8.121, 95% CI -10.338 to -5.905; PM10 β -4.518, 95% CI -6.680 to -2.357). Verbal memory showed similar trends though less pronounced.

All measured pollutants—including NO2, NOx, PM10, PM2.5, PMcoarse, and PM2.5abs—were associated with lower ACE-III scores at age 69, reflecting impaired global cognitive functioning (e.g., NO2 β -0.589, 95% CI -0.921 to -0.257).

Neuroimaging revealed that higher NOx exposure correlated with smaller hippocampal volume (β -0.088, 95% CI -0.172 to -0.004), while increased NO2 and PM10 exposures were linked to enlarged ventricular volume (NO2 β 2.259, 95% CI 0.457 to 4.061; PM10 β 1.841, 95% CI 0.013 to 3.669), suggesting neurodegenerative changes consistent with aging and dementia pathology. White matter hyperintensity volume and whole brain volume did not show strong associations.

Expert Commentary

This study’s strengths lie in its life-course exposure assessment within a well-characterized birth cohort and the integration of cognitive testing with advanced neuroimaging. The findings contribute to the growing epidemiological and mechanistic evidence implicating ambient air pollution as a modifiable risk factor for cognitive decline and brain structural alterations. Importantly, effects were observed for both gaseous pollutants (NO2, NOx) and particulate matter, supporting multifactorial neurotoxic mechanisms including oxidative stress, inflammation, and cerebrovascular injury.

Limitations include potential residual confounding, imprecision in individual-level pollution exposure estimates, and generalizability confined to a UK-born cohort. The study adjusted for early-life pollution exposures, strengthening causal inference, but disentangling cumulative life-course effects remains challenging.

Clinical implications emphasize public health efforts to reduce air pollution exposure starting in midlife or earlier as a strategy to mitigate dementia risk. Future research should investigate interventions to protect vulnerable populations and elucidate biological pathways linking environmental toxins to neurodegeneration.

Conclusion

The study robustly demonstrates associations between increased midlife exposure to ambient air pollution and subsequent cognitive decline, poorer cognitive state, and adverse brain structural changes in later life. These results reinforce environmental air quality as a critical, modifiable factor influencing brain health and aging trajectories. Addressing air pollution exposure throughout the life course offers a promising avenue to preserve cognitive function and reduce dementia burden globally.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institute for Health and Care Research, Medical Research Council, Alzheimer’s Research UK, Alzheimer’s Association, MRC Dementias Platform UK, and Brain Research UK.

References

Canning T, Arias-de la Torre J, Fisher HL, et al. Associations between life course exposure to ambient air pollution with cognition and later-life brain structure: a population-based study of the 1946 British Birth Cohort. Lancet Healthy Longev. 2025 Jul;6(7):100724. doi: 10.1016/j.lanhl.2025.100724. Epub 2025 Jul 17. PMID: 40684776.

Peters R, Ee N, Peters J, et al. Air Pollution and Dementia: A Systematic Review. J Alzheimers Dis. 2019;70(s1):S145-S163. doi:10.3233/JAD-180631

Peters R, Magaña J, Peters J. The potential role of environmental air pollution in dementia and cognitive decline: a review. Public Health. 2022;206:94-101. doi:10.1016/j.puhe.2022.04.012