Introduction and Context

Polyarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis (poly-JIA) — arthritis affecting five or more joints in children — is one of the more aggressive paediatric inflammatory arthritides. In 2025 the Pan‑American League of Associations for Rheumatology (PANLAR) published a focused guideline in Lancet Child & Adolescent Health specifically addressing pharmacological treatment of non-systemic poly-JIA across Latin America (Gutiérrez‑Suárez et al., Lancet Child Adolesc Health 2025). The guideline was created by a region-wide panel of paediatric rheumatologists and methodologists using GRADE methodology and rigorous systematic review of the evidence.

Why this guideline now? Three forces prompted PANLAR to develop region-specific recommendations:

– Clinical gaps and inequities: children in Latin America often face delayed diagnosis, limited access to paediatric rheumatologists, and restricted availability of costly biologic therapies, producing higher disease activity and worse outcomes compared with high-income countries (Consolaro et al., Lancet Child Adolesc Health 2019).

– New evidence and therapeutics: recent randomized trials and registry data clarify optimal methotrexate dosing and routes, support early combination therapy with biologics, and expand the evidence base for JAK inhibitors and other biologics in refractory disease (Ruperto et al., Lancet 2021; Ramanan et al., Lancet 2023).

– Need for pragmatic, resource-aware guidance: WHO’s Model List of Essential Medicines for Children now includes several DMARDs and biologics, but availability remains uneven; PANLAR aimed to combine best evidence with realistic alternatives for constrained health systems.

The PANLAR recommendations focus narrowly on pharmacologic management (not diagnosis, vaccination, or long-term monitoring), and adopt a practical clinical phenotype of poly-JIA that spans several ILAR categories (RF‑positive/negative polyarthritis, extended oligoarthritis, undifferentiated polyarthritis) while excluding systemic JIA, psoriatic JIA and enthesitis‑related arthritis which require separate guidance.

New Guideline Highlights

Major themes and takeaways for clinicians:

– Treat-to-target: aim for drug-free inactive disease using a JADAS‑27–guided approach, with strict follow-up every ~3 months to escalate therapy when needed.

– Methotrexate remains the cornerstone: start nbDMARD therapy early (methotrexate preferred) and allow a 3‑month trial for low–moderate disease activity without poor prognosis.

– Escalate appropriately: in moderate disease with poor prognostic features or high disease activity, combine parenteral methotrexate (15 mg/m2/week subcutaneous) with a biologic (first‑line anti‑TNF agents preferred).

– Region-aware alternatives: when biologics are unavailable, consider triple nbDMARD therapy (methotrexate + sulfasalazine ± hydroxychloroquine) or leflunomide for methotrexate intolerance/contraindication.

– Corticosteroids: limited, low‑dose bridging steroids (0.2 mg/kg/day prednisone up to 10 mg/day) are endorsed as an expert opinion for short periods (aim to stop within 3 months).

– Uveitis: adalimumab is recommended for JIA‑associated uveitis refractory to methotrexate.

– Biologic switching: on primary anti‑TNF failure (within 3 months), switch to a different biologic class; on secondary failure, switching to another anti‑TNF may be acceptable.

Key practical messages for busy clinicians: start methotrexate early, measure disease activity using JADAS‑27 thresholds, escalate without delay in poor prognosis or persistent activity, use local alternatives pragmatically when biologics are inaccessible, and minimize steroid exposure.

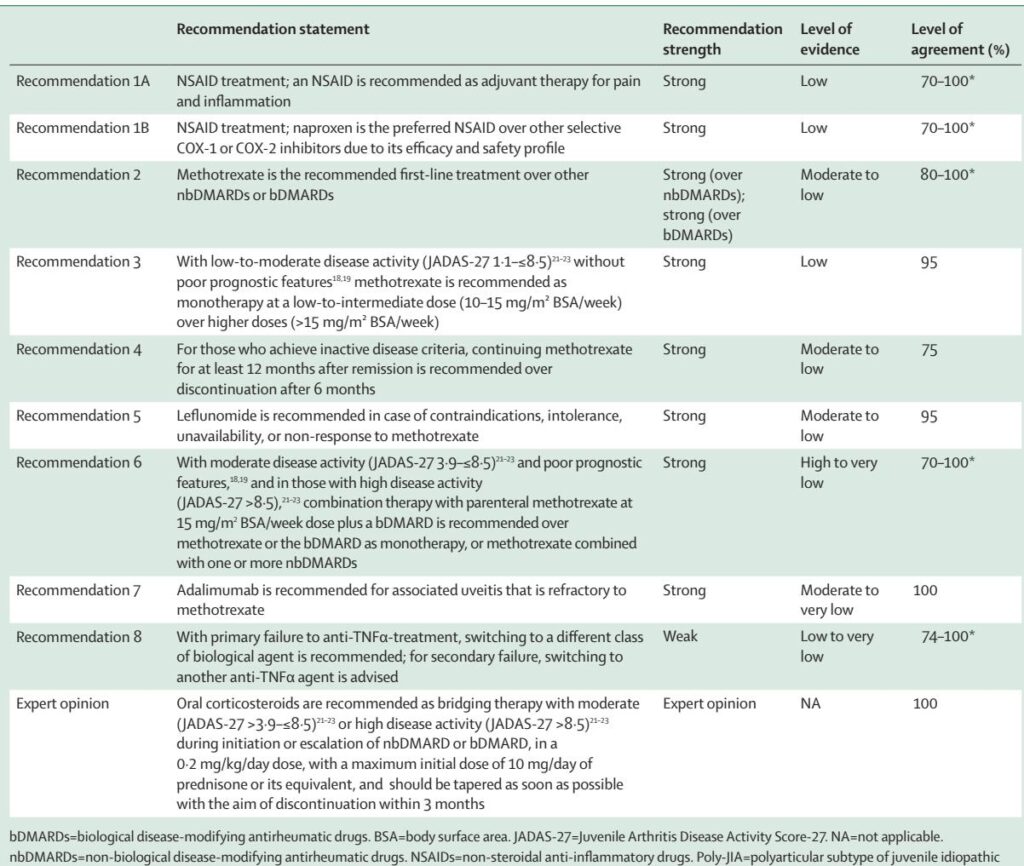

Updated Recommendations and Key Changes vs Prior Guidance

PANLAR synthesised evidence up to Feb 23, 2022, and delivered eight formal recommendations plus one expert opinion. Important differences or clarifications compared with earlier guidance (notably the 2019 ACR/Arthritis Foundation JIA guideline and international treat‑to‑target statements) include:

– Regional adaptation: PANLAR explicitly frames recommendations around Latin America’s resource variability and proposes temporary alternatives (leflunomide, triple nbDMARD) when biologics are not available — a pragmatic addition compared with ACR and some international algorithms that assume biologic access.

– Phenotype definition: rather than strict ILAR categories, PANLAR endorses a broader polyarticular phenotype for therapeutic decision‑making — aligning with growing recognition that ILAR divisions may not always match therapeutic needs.

– Methotrexate route and dosing nuance: PANLAR recommends low–intermediate oral dosing (10–15 mg/m2/week) for low–moderate activity and supports subcutaneous methotrexate at 15 mg/m2/week (up to 25 mg/week) when higher doses are needed or oral absorption is suspected insufficient — reinforcing evidence that parenteral administration improves bioavailability without added safety concerns.

– Duration before withdrawal: for patients achieving inactive disease, PANLAR advises continuing methotrexate for at least 12 months after remission rather than stopping at 6 months — a cautious stance informed by relapse risk data (even though randomized withdrawal trials have mixed results).

– Biologic sequencing: PANLAR gives practical recommendations on switching — recommending a class switch for primary anti‑TNF failure and an intra-class switch for secondary failure — consistent with emerging paediatric data and adult rheumatology practice.

These changes reflect both new trial data and a pragmatic emphasis on equity and feasibility in Latin American practice.

Topic-by-Topic Recommendations

Below is a concise, clinician-focused synthesis of PANLAR’s core recommendations, with GRADE strength and evidence levels as reported by the guideline authors.

Recommendations (numbered as in PANLAR):

– Recommendation 1A — NSAIDs as adjuvant therapy

– Statement: Use an NSAID as adjuvant therapy for pain and inflammation in poly‑JIA.

– Strength: Strong (evidence: Low). Trial data are limited but clinical practice supports symptomatic benefit.

– Note: Trial for at least 8 weeks; do not delay DMARD initiation.

– Recommendation 1B — Naproxen preferred when available

– Statement: Naproxen is the preferred NSAID in children for efficacy/safety profile.

– Strength: Strong (evidence: Low). If contraindicated, clinician may use alternative paediatric‑approved NSAIDs.

– Recommendation 2 — Methotrexate as first‑line nbDMARD

– Statement: Methotrexate is the recommended first‑line DMARD over other nbDMARDs or biologics for most poly‑JIA presentations.

– Strength: Strong (evidence: Moderate–Low). Supported by RCTs and registry data showing remission and improved quality of life in ~60–70%.

– Practical dosing: 10–15 mg/m2/week oral for low–moderate disease; change to parenteral at 15 mg/m2/week when higher doses are required.

– Recommendation 3 — Dose selection for methotrexate

– Statement: For low–moderate activity without poor prognostic features, use low–intermediate methotrexate doses (10–15 mg/m2/week) over >15 mg/m2/week.

– Strength: Strong (evidence: Low). Higher doses showed no clear incremental benefit in an RCT.

– Recommendation 4 — Duration after remission

– Statement: If inactive disease is achieved, continue methotrexate for at least 12 months post‑remission rather than discontinuing at 6 months.

– Strength: Strong (evidence: Moderate–Low). Observational data show longer time in remission reduces flare risk.

– Recommendation 5 — Leflunomide as alternative

– Statement: Use leflunomide when methotrexate is contraindicated, not tolerated, unavailable, or ineffective.

– Strength: Strong (evidence: Moderate–Low). RCTs show leflunomide is effective but generally less effective short‑term than methotrexate; useful as an alternative in constrained settings.

– Recommendation 6 — Combination therapy with biologic for moderate/high disease

– Statement: For moderate disease with poor prognosis or high disease activity (JADAS‑27 thresholds specified), combine parenteral methotrexate (15 mg/m2/week) with a biologic (preferably anti‑TNF) rather than either alone or methotrexate plus other nbDMARDs.

– Strength: Recommendation supported though quality spans High to Very Low depending on the comparison and outcome; pooled data show earlier/remission benefit with combination therapy.

– Regional alternative: If biologics are unavailable, consider triple nbDMARD therapy (methotrexate + sulfasalazine + hydroxychloroquine) as a temporary strategy.

– Recommendation 7 — Adalimumab for refractory uveitis

– Statement: For JIA‑associated uveitis refractory to methotrexate, add adalimumab.

– Strength: Strong (evidence: Moderate to Very Low). Supported by an RCT showing reduced treatment failure when adalimumab is added to methotrexate.

– Recommendation 8 — Biologic switching strategy

– Statement: For primary anti‑TNF failure (3 months), switching to another anti‑TNF agent is reasonable.

– Strength: Variable (evidence: Low to Very Low). Supported by trials and registries for tocilizumab, abatacept, golimumab, rituximab, and JAK inhibitors in refractory disease.

– Expert opinion (steroid bridging)

– Statement: Short‑term, low‑dose oral corticosteroids (0.2 mg/kg/day prednisone up to 10 mg/day) may be used as bridging therapy in moderate or high disease while initiating/escalating nbDMARDs or biologics. Taper and discontinue as soon as feasible, aiming within 3 months.

– Evidence: Expert opinion (very low-quality evidence). This mirrors ACR conditional recommendations and CARRA consensus plans.

Operational definitions and activity thresholds:

– PANLAR prioritises JADAS‑27 as the disease activity metric: inactive disease ≤1.0; low 1.1–3.8; moderate 3.9–8.5; high >8.5.

– Poor prognostic features include symmetric disease, involvement of wrist/hip/cervical spine/TMJ, elevated inflammatory markers, delayed diagnosis, RF or anti‑CCP positivity, and early erosions.

Follow-up and escalation policy:

– Reassess every 3 months; define lack of response (LR) as JADAS‑27 no lower than 3 months prior, and insufficient response (IR) as clinically inadequate improvement — prompt treatment change if LR or IR.

Special populations and safety considerations:

– The guideline excludes systemic JIA, psoriatic JIA and ERA; separate pathways are required for those entities.

– Tuberculosis and infection screening: PANLAR did not provide unified latent TB screening guidance (important in the region); clinicians should follow local national TB guidance before starting biologics.

Expert Commentary and Insights

The PANLAR panel combined evidence appraisal with extensive regional clinical experience. Key expert insights and controversies include:

– Balancing ideal care with availability: multiple panel members emphasise that while bDMARDs (anti‑TNFs, tocilizumab, abatacept) are the most effective escalation options, practical constraints often force clinicians to use nbDMARD combinations or leflunomide. PANLAR explicitly frames these alternatives as temporary, not ideal, measures until biologics can be procured.

– ILAR classification vs. phenotype: several experts argued that strict ILAR categories are less helpful when making treatment decisions; instead, phenotype (polyarticular joint burden, activity and prognosis markers) best guides therapy. This aligns with international discussions about revising JIA taxonomy (Martini et al., J Rheumatol 2019).

– Methotrexate route: while RCTs show similar ACR Pedi responses for oral vs parenteral methotrexate, pharmacokinetic studies and clinical experience favour subcutaneous administration when doses reach ~15 mg/m2/week, especially in young children with variable oral absorption.

– Duration of therapy after remission: the panel favoured 12 months of methotrexate after achieving inactive disease — even though randomized data are mixed — because time in inactive disease appears to reduce flare risk.

– Biologic sequencing and anti‑drug antibodies: testing for anti‑drug antibodies is recommended by the panel where available but not commonly performed in many Latin American centres. This gap affects decisions about switching vs dose escalation.

– Corticosteroid role: unanimous agreement that systemic steroids must be minimized; however, short bridging courses remain a pragmatic tool in high‑activity situations where immediate disease control is required.

– Need for local data and registries: experts strongly recommended enhancing regional registries, pharmaco‑economic studies, and operational research to define outcomes in Latin American settings and to advocate for equitable medication access.

Practical Implications

For clinicians and health systems in Latin America, PANLAR’s guideline has several practical consequences:

1) Clinical pathway (concise):

– Newly diagnosed poly‑JIA or low activity without poor prognosis: start methotrexate (10–15 mg/m2/week), NSAID for symptoms. Reassess at 3 months.

– Low–moderate disease with inadequate response after 3 months or poor prognostic features: consider parenteral methotrexate (15 mg/m2/week) and escalate to combination with a biologic if available.

– Moderate disease with poor prognosis or high disease activity: combine parenteral methotrexate 15 mg/m2/week with a biologic (anti‑TNF preferred).

– If biologics unavailable: consider triple nbDMARD therapy (methotrexate + sulfasalazine ± hydroxychloroquine) or leflunomide when methotrexate is not possible.

– JIA‑associated uveitis refractory to methotrexate: add adalimumab.

2) Health-system considerations:

– Prioritise procurement and equitable distribution of essential medicines (methotrexate, hydroxychloroquine, sulfasalazine, naproxen) and advocate for biosimilar access to improve biologic availability.

– Implement JADAS‑27 in routine clinical notes to standardise treat‑to‑target care and support audits and registry data collection.

– Strengthen latent TB screening and infection surveillance when initiating immunosuppressives (local protocols required).

3) Patient and family counselling:

– Explain the treat‑to‑target goal of inactive disease and the likely multi‑step pathway (starting methotrexate, possible escalation to biologics).

– Discuss risks of steroids and the plan to minimise their use.

– Emphasise adherence (methotrexate weekly dosing) and the importance of regular monitoring for toxicity and disease activity.

Clinical Vignette (Illustrative)

Emma, a 10‑year‑old girl, presents with a 4‑month history of symmetric arthritis involving wrists, MCPs and knees. Baseline JADAS‑27 = 12 (high disease activity); ESR elevated; RF negative; early radiographic joint space narrowing in wrist. Diagnosis: polyarticular JIA with poor prognostic features.

Application of PANLAR guidance:

– Start parenteral methotrexate 15 mg/m2/week subcutaneously and naproxen for symptom control. Begin low‑dose oral prednisone 0.2 mg/kg/day (max 10 mg/day) as short bridging therapy while waiting for methotrexate effect, with plan to taper within 6–12 weeks and stop by 3 months.

– Given high disease activity and poor prognostic features, plan for early combination with an anti‑TNF biologic (e.g., etanercept or adalimumab) as soon as funding/approval is secured — monitor JADAS‑27 every 3 months and escalate promptly if LR/IR.

– If biologic access is delayed, consider adding sulfasalazine and hydroxychloroquine (triple therapy) temporarily while pursuing biologic procurement.

Research Needs and Future Directions

PANLAR highlights several priorities:

– Regional registry data capturing long‑term outcomes, treatment patterns, adverse events and access barriers.

– Pragmatic trials comparing triple nbDMARD therapy versus biological escalation in resource‑limited settings, and cost‑effectiveness studies of biosimilars and other access strategies.

– Operational research on latent TB screening strategies and infection risk mitigation in high endemicity settings.

– Studies validating treat‑to‑target thresholds and biomarker‑guided therapy escalation in diverse populations.

References

(Selected, verifiable key sources cited in the guideline and relevant literature)

– Gutiérrez‑Suárez R, Appenzeller S, Silva CA, et al. Treatment of polyarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis in Latin America: recommendations from the Pan‑American League of Associations for Rheumatology. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2025;9:508–518.

– Ringold S, Angeles‑Han ST, Beukelman T, et al. 2019 American College of Rheumatology/Arthritis Foundation Guideline for the Treatment of Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019;71:846–863.

– Ravelli A, Consolaro A, Horneff G, et al. Treating juvenile idiopathic arthritis to target: recommendations of an international task force. Ann Rheum Dis. 2018;77:819–828.

– Giannini EH, Brewer EJ, Kuzmina N. Methotrexate in resistant juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. 1992;326:1043–1049.

– Foell D, Wulffraat N, Wedderburn LR, et al. Methotrexate withdrawal at 6 vs 12 months in juvenile idiopathic arthritis in remission: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2010;303:1266–1273.

– Ruperto N, Brunner HI, Synoverska O, et al. Tofacitinib in juvenile idiopathic arthritis: a phase 3 randomised trial. Lancet. 2021;398:1984–1996.

– Ramanan AV, Quartier P, Okamoto N, et al. Baricitinib in juvenile idiopathic arthritis: a phase 3 randomised trial. Lancet. 2023;402:555–570.

– Ramanan AV, Dick AD, Jones AP, et al. Adalimumab in combination with methotrexate for refractory uveitis associated with juvenile idiopathic arthritis: RCT. Health Technol Assess. 2019;23:1–140.

– Consolaro A, Giancane G, Alongi A, et al. Phenotypic variability and disparities in treatment and outcomes of childhood arthritis throughout the world. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2019;3:255–263.

– WHO Model List of Essential Medicines for Children (9th List). World Health Organization. 2023. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-MHP-HPS-EML-2023.0

(Additional supporting citations from PANLAR reference list are available in the original guideline.)