Highlights

- The traditional Pooled Cohort Equations (PCE) model remains widely used for 10-year ASCVD risk estimation but typically overestimates risk, especially in patients undergoing statin therapy.

- The newly developed PREVENT model accounts for statin exposure during follow-up, offering improved risk calibration in treated populations.

- Both models demonstrate similar discrimination (C-statistics approximately 0.72-0.73), but differ in calibration depending on statin treatment status.

- Clinicians should consider patient statin use when selecting a prediction model to avoid risk underestimation or overestimation and optimize personalized prevention strategies.

Background

Cardiovascular disease, particularly atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD), remains a leading cause of mortality worldwide. Accurate estimation of absolute 10-year ASCVD risk is fundamental to guiding primary prevention, such as statin initiation, and tailoring individualized treatment approaches. The Pooled Cohort Equations (PCE), introduced around 2013 in the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association lipid guidelines, have become the standard tool for risk stratification. However, limitations include lack of consideration for statin therapy initiated during the follow-up, which may attenuate event rates and affect calibration.

To address this, the PREVENT (Prediction of cardiovascular disease Events based on Varying statin Exposure during follow-up a Notional Estimation of Treatment effect) model has been developed, incorporating dynamic statin exposure into risk estimation. Nonetheless, there is limited comparative evidence on the real-world performance of PREVENT relative to PCE, especially with respect to patients’ statin use. This review synthesizes key findings from the recent large retrospective cohort study by Lee et al. (2025) and contextualizes these within the broader cardiovascular risk prediction literature.

Key Content

Study Design and Population

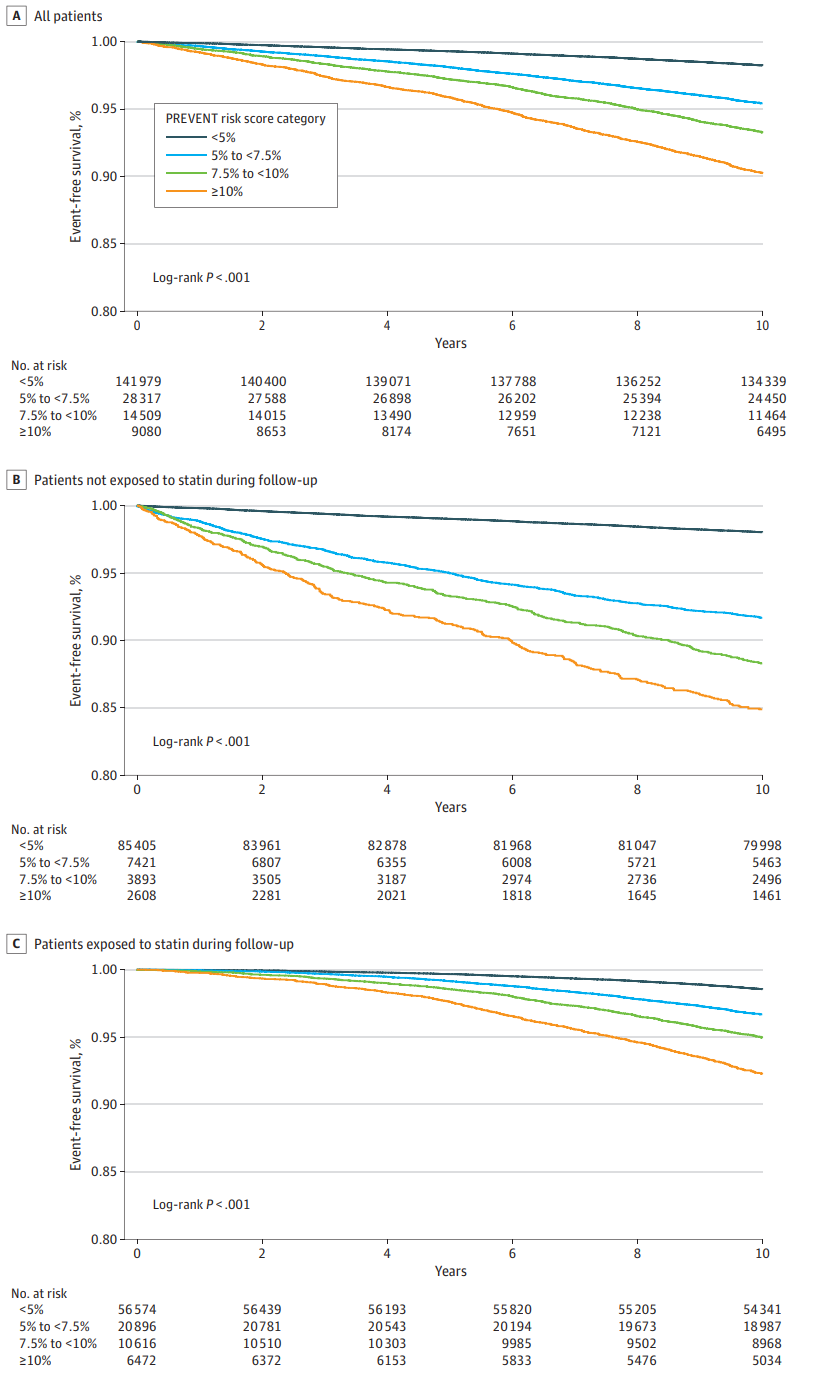

Lee et al. conducted a large retrospective cohort analysis including 193,885 adults without diabetes or prior ASCVD in a single integrated health system, followed for up to 10 years (2013-2023). Comprehensive data on demographic and clinical risk factors, incident ASCVD events, and statin prescriptions were collated. The cohort was stratified by statin exposure during follow-up to examine model performance across treated and untreated groups.

The primary analyses compared the 10-year ASCVD risk estimates generated by the PCE and PREVENT models against observed event rates. Model discrimination was assessed by the concordance statistic (C-statistic), and calibration was evaluated by comparing predicted versus observed risks within clinically relevant risk strata.

Model Discrimination and Calibration

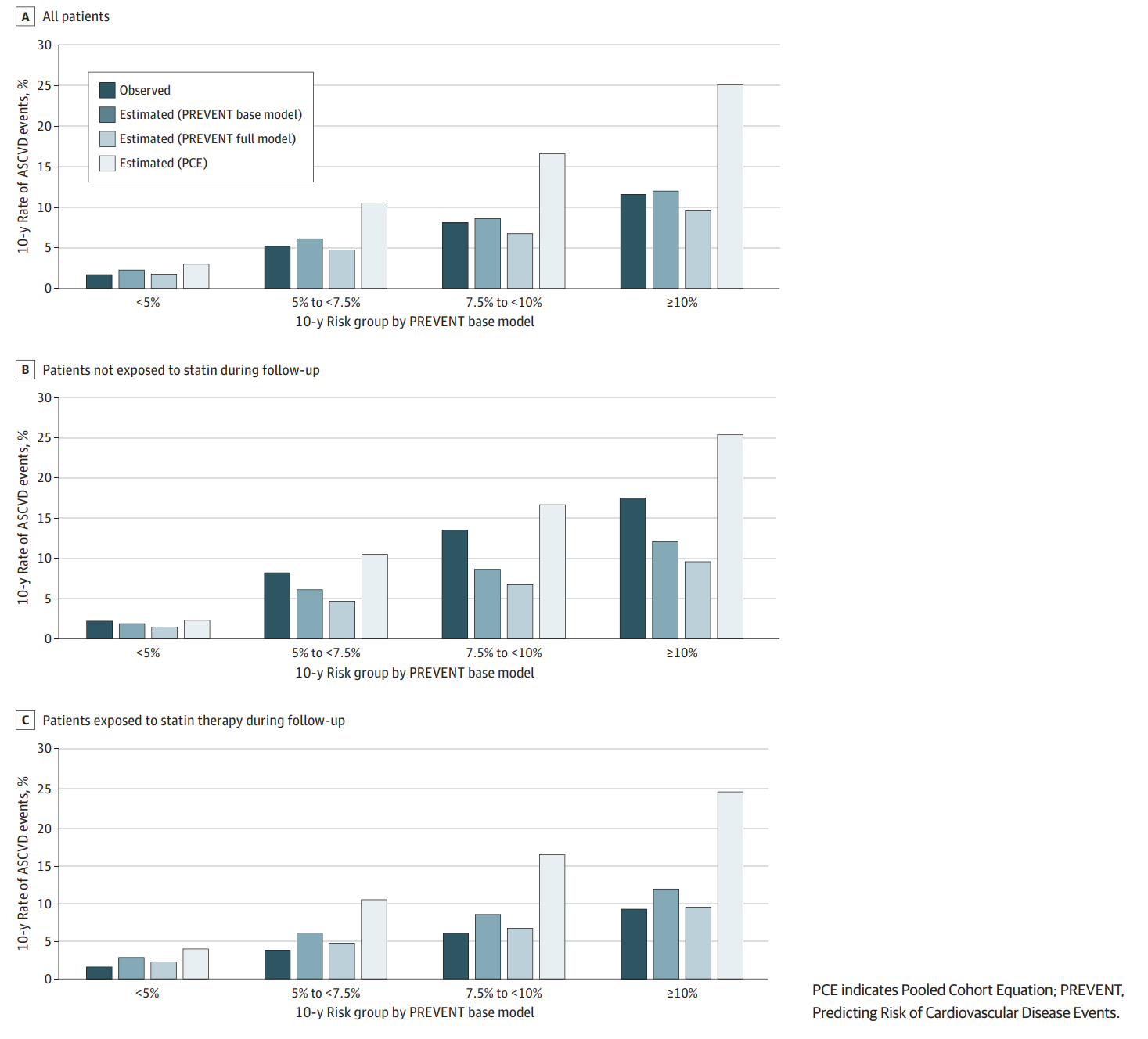

– Both PREVENT and PCE yielded comparable discriminatory ability for ASCVD events, with C-statistics of 0.723 and 0.725, respectively.

– The PCE model generally overestimated 10-year risk across the cohort. For instance, in the 5%–7.5% predicted risk group by PCE, the actual observed risk was only 3.6%.

– The PREVENT model better aligned predicted and observed risks overall, with more accurate calibration in patients exposed to statins. The same 5%–7.5% predicted risk group had an observed risk of 5.2% per PREVENT predictions.

Kaplan-Meier by PREVENT model

Kaplan-Meier by ASCVD model

Stratified Analyses by Statin Exposure

– Among patients undergoing statin therapy during follow-up, PREVENT’s predictions closely matched observed risk, reflecting its adjustment for treatment impact.

– Conversely, in patients who did not receive statins, PREVENT underestimated risk (eg, 5%–7.5% predicted risk group had observed event rate of 8.2%), whereas PCE predictions were more consistent with actual outcomes.

Clinical Implications

The findings underscore the importance of incorporating statin exposure into ASCVD risk prediction. In treated patients, the PREVENT model offers superior risk calibration, helping avoid overestimation that may lead to unnecessary intensification or overtreatment. However, PREVENT’s underestimation in untreated patients may risk missed opportunities for preventive therapy initiation. Therefore, clinicians should interpret PREVENT estimates within the context of patient treatment status.

Furthermore, routine use of PCE may continue to be appropriate in statin-naïve populations given its reasonable performance. The results advocate for a nuanced, personalized approach combining risk tools with clinical judgment, particularly regarding timing and adherence of statin use.

Context from Related Studies

Several recent studies have highlighted limitations of the PCE in different demographic and clinical subgroups. For example, PCE tends to overestimate cardiovascular risk in low- to moderate-risk populations globally and may underperform in ethnic minorities or patients with HIV. Adjustments and recalibrations have been proposed to improve PCE accuracy, though none fully account for dynamic statin exposure.

Retrospective analyses in East Asian populations (e.g., Korean cohorts) have validated PCE utility for guiding statin therapy, but indicate underutilization of statins among patients with high predicted risk. Additionally, revised PCE algorithms have been developed to reduce racial disparities in risk estimation and statin eligibility, supporting adaptation of risk assessment tools to population specifics.

Expert Commentary

The comparative performance of ASCVD risk prediction models is central to preventive cardiology. The introduction of PREVENT represents a methodological advance by explicitly modeling statin treatment effects, addressing a key limitation of traditional tools like PCE. Nonetheless, as demonstrated by Lee et al., its use must be contextualized carefully:

– The slight trade-off in discrimination balanced with improved calibration in treated patients supports its use in patients already receiving or likely to initiate lipid-lowering therapy.

– PREVENT’s underestimation risk in untreated patients suggests that using it in isolation may delay preventive interventions.

– Incorporating treatment adherence, statin intensity, and patient-specific factors could further refine PREVENT but require more granular data.

– Current guidelines (ACC/AHA, ESC) emphasize absolute risk estimation for statin initiation; emerging data from PREVENT may inform future guideline iterations.

Limitations of the study include its retrospective design, single healthcare system setting, and lack of detailed statin dosing and adherence information, which may influence risk estimates and generalizability. Future research should involve diverse multicenter cohorts and prospective validation to confirm findings.

Conclusion

Overall, while the Pooled Cohort Equations remain a robust starting point for ASCVD risk assessment, the PREVENT model offers refined risk estimation by adjusting for statin exposure, enhancing accuracy in treated populations. Clinicians should integrate both models’ strengths, interpret estimates alongside clinical context, and consider statin therapy status to optimize risk stratification and preventive strategies. Further validation and enhancement of PREVENT are warranted to ensure broad applicability across diverse populations and treatment patterns.

References

- Lee M, Onwuzurike J, Wu Y, Palmer-Toy DE, An J, Chen W. PREVENT and PCE Models for Estimating ASCVD Risk Stratified by Statin Exposure. JAMA Netw Open. 2025;8(9):e2532164. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2025.32164 IF: 9.7 Q1

- Kalani R, Feinstein MJ, Aberg JA, et al. Performance of the pooled cohort equations and D:A:D risk scores among individuals with HIV in a global cardiovascular disease prevention trial: a cohort study leveraging data from REPRIEVE. Lancet HIV. 2025;12(2):e118-e129. doi:10.1016/S2352-3018(24)00276-5 IF: 13.0 Q1

- Jeong H, Eun Y, Kim Y, et al. Statin use and outcome risks according to predicted CVD risk in Korea: A retrospective cohort study. PLoS One. 2021;16(1):e0245609. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0245609 IF: 2.6 Q2

- Virmani SA, Franceschi D, Lennon RJ, et al. Estimated Cardiovascular Risk and Guideline-Concordant Primary Prevention With Statins: Retrospective Cross-Sectional Analyses of US Ambulatory Visits Using Competing Algorithms. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther. 2020;25(1):27-36. doi:10.1177/1074248419866153 IF: 2.8 Q2

- Saad M, Ashley EA. Primary Prevention With Statins: ACC/AHA Risk-Based Approach Versus Trial-Based Approaches. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;66(24):2699-2709. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2015.09.089 IF: 22.3 Q1

- Goff DC Jr, Lloyd-Jones DM, Bennett G, et al. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the assessment of cardiovascular risk: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63(25 Pt B):2935-2959. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2013.11.005 IF: 22.3 Q1