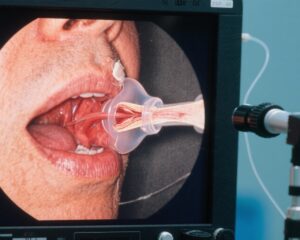

Introduction: Unveiling the Mouth-Heart Connection

When we think of factors that cause heart attacks, cholesterol, high blood pressure, smoking, and diabetes usually come to mind. Yet, a groundbreaking study published in the Journal of the American Heart Association (JAHA) by researchers from Tampere University, Finland, and collaborators worldwide has uncovered a surprising culprit lurking in our mouths — a common type of oral bacteria called Viridans streptococci.

This discovery adds a new dimension to our understanding of heart disease, highlighting how neglected oral health can silently escalate the risk of deadly cardiovascular events.

Beyond Cholesterol: Oral Bacteria’s Role in Heart Attack Risk

The traditional view of heart attacks centers on the buildup and rupture of atherosclerotic plaques — fatty deposits in the arteries that narrow blood flow. High cholesterol, hypertension, smoking, and diabetes continue to be major contributors. However, chronic inflammation is emerging as a crucial player in destabilizing plaques, making them prone to rupture.

The recent Tampere study provides compelling evidence at the tissue level that Viridans streptococci, a bacterial group normally residing in the mouth, can inhabit these plaques. Their presence sparks inflammation that weakens plaque integrity, increasing the risk of rupture and subsequent heart attack.

This challenges the simplistic “cholesterol only” model and underscores the complexity of atherosclerosis as a chronic inflammatory disease.

Who Are These Culprits? Meet Viridans Streptococci

Viridans streptococci are a group of bacteria naturally found in the oral cavity. They play a role in forming dental plaque but don’t usually cause problems under healthy conditions. However, situations like gum inflammation, bleeding, or dental procedures (e.g., tooth extraction, root canal treatment) can enable these bacteria to enter the bloodstream temporarily, a phenomenon called bacteremia.

Until now, medicine considered such bloodstream presence as transient and harmless because the immune system quickly clears these microbes. The new study overturns this assumption by demonstrating that these bacteria can survive inside atherosclerotic plaques, forming protective structures called biofilms that shield them from immune attack.

Scientific Evidence: Bacteria Inside Dangerous Arterial Plaques

The researchers analyzed coronary artery plaques from 121 patients who died suddenly from coronary heart disease, as well as samples from 96 patients undergoing vascular surgery.

Key findings include:

– About 60% of atherosclerotic plaques contained bacterial DNA.

– 42% of these plaques had DNA specifically from Viridans streptococci.

– Healthy blood vessel samples rarely showed such bacteria.

Immunohistochemical stains revealed biofilm-like formations of these bacteria embedded within the plaque’s lipid core and fibrous caps, areas critical for plaque stability. These biofilms were located near fragile new blood vessels within plaques, hinting at their possible route of entry.

Moreover, these bacteria-associated plaques showed higher inflammation markers and were linked with plaque rupture and thrombosis — the immediate cause of many heart attacks.

The Stealth Strategy: How Bacteria Evade Detection and Trigger Inflammation

Viridans streptococci deploy a multi-step approach to colonize plaques and incite damage:

1. Entry through New Vessels: Atherosclerotic plaques develop fragile new microvessels with permeable walls, offering a “backdoor” for bacteria carried in the bloodstream to infiltrate the plaque interior.

2. Fortifying with Biofilms: Once inside, bacteria assemble into biofilms by secreting sticky substances that form a protective matrix. This biofilm acts like an invisible cloak, preventing immune cells such as macrophages from recognizing and attacking them.

3. Activating Inflammation: Under triggers like blood pressure spikes or infections, some bacteria disperse from the biofilm and invade the plaque’s fibrous cap. This sparks immune activation, especially through Toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2) and nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) pathways, unleashing a cascade of inflammatory signals and enzymes.

4. Plaque Destabilization and Rupture: The inflammatory response degrades collagen and thins the fibrous cap, making it fragile and prone to rupture. Once ruptured, the plaque contents contact blood, triggering clot formation.

This cascade can block coronary arteries swiftly, precipitating acute myocardial infarction (heart attack), or affect cerebral vessels, causing strokes.

Case Illustration: John’s Hidden Risk

John, a 58-year-old man with controlled hypertension and mildly elevated cholesterol, always brushed his teeth but often skipped flossing and rarely visited a dentist. He suffered frequent gum bleeding but dismissed it as minor.

One day, he experienced sudden chest pain and was diagnosed with a heart attack. Detailed examination found significant plaque rupture in his coronary arteries. Further analysis revealed Viridans streptococci biofilms embedded in the ruptured plaques.

John’s case exemplifies how subtle oral health issues can contribute unseen to cardiovascular events, emphasizing prevention and vigilance.

Why This Research Matters

This study reshapes our understanding of cardiovascular disease by:

– Highlighting the interplay between oral microbiota and systemic inflammation.

– Supporting the notion that atherosclerosis is more than just a lipid storage disorder; it’s a chronic inflammatory disease.

– Identifying a novel pathological mechanism linking oral health and sudden cardiac death.

Therapeutic implications include recognizing oral hygiene and infection control as integral to heart disease prevention strategies. However, conventional antibiotics struggle to penetrate biofilms, and widespread antibiotic use risks resistance and microbiome disruption.

Practical Recommendations for Protecting Your Heart via Oral Health

The study underscores the importance of maintaining oral health as a proactive measure against cardiovascular events.

Key practices include:

– Consistent Oral Hygiene: Brush twice daily using the Bass technique, floss or use interdental brushes, and seek professional dental cleanings at least once a year.

– Address Gum Symptoms Promptly: Do not ignore gum redness, swelling, bleeding, or bad breath. Early dental intervention can halt progression to chronic periodontal inflammation.

– Preoperative Precautions: Patients with known heart conditions or valve diseases undergoing invasive dental work should consult cardiologists and dentists to assess the need for prophylactic antibiotics.

– Avoid Antibiotic Overuse: Routine use of antibiotics to prevent heart attacks is not recommended due to ineffectiveness against biofilms and risk of adverse effects.

– Maintain Cardiovascular Health: Control blood pressure, lipids, and blood sugar; avoid tobacco; limit alcohol; eat sensibly; and stay physically active.

Expert Insights

Dr. Paula Karhunen, lead author of the JAHA study, emphasizes: “Our findings reveal that oral bacteria are not innocent bystanders but active contributors to atherosclerotic plaque instability. This provides a strong rationale for integrating dental care into cardiovascular prevention protocols.”

Conclusion: From Mouth to Heart, Prevention Starts At Home

The emerging data decisively link oral bacteria — particularly Viridans streptococci — with increased risk of heart attack through their infiltration and inflammatory activity within arterial plaques. This discovery calls for a holistic approach to cardiovascular health incorporating meticulous oral hygiene and timely dental care.

Ultimately, simple daily habits like proper brushing, flossing, and regular dental visits may be some of the most effective defenses against heart disease.

References

Karhunen PJ, Pessi T, Karhunen V, et al. Viridans Streptococcal Biofilm Evades Immune Detection and Contributes to Inflammation and Rupture of Atherosclerotic Plaques. J Am Heart Assoc. 2025; DOI:10.1161/JAHA.125.XXXXXX

Other references:

– Tonetti MS, Van Dyke TE. Periodontitis and Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease: Consensus Report of the Joint EFP/AAP Workshop on Periodontitis and Systemic Diseases. J Clin Periodontol. 2013;40(Suppl 14):S24–S29.

– Lockhart PB, Brennan MT, Thornhill M, et al. Poor Oral Hygiene as a Risk Factor for Infective Endocarditis–Related Bacteremia. J Am Dent Assoc. 2009;140(10):1238-1244.